Every few years, I get a new phone. This is one of those years, and today is the day. A shiny blue iPhone 15 Pro Max is wending its way too me even as I type.

Back when I had a large, constant stream of income, I’d upgrade my phone every year or two. Dumb? Yes. But I did it. Nowadays, though, I hold out until I have a compelling reason to upgrade. In this case, my old phone has a failing battery. Plus, I’m keen on the new phone’s camera. I gave myself permission to upgrade this year. And I’m hoping to go even longer this time before upgrading (my goal is 4+ years instead of three).

This year, I’m conducting an experiment. I’m generally a fan of smaller phones rather than larger ones. If Apple offered a small phone (like an iPhone SE) that had all of the specs of the large phone, I’d buy the small phone. But Apple does not offer such a phone. Too, I use an iPad Mini for stuff like reading, playing games, watching movies. I’m curious: Could an iPhone Pro Max replace an iPad Mini for these use cases? Could I get away with just having one device? I think it’s possible, so this time I’m buying a jumbo-sized phone as an experiment. If I don’t like it — and there’s a solid chance I won’t — then I’ll revert to a regular size in a few years.

As an aside, I’m one of those weirdos that doesn’t use a case for his phone. Why not? I tell this true story.

For eight years — from 2007 to 2015 — I was caseless and never damaged a phone. Then Jesse Mecham (from You Need a Budget) sent me a customized case for my birthday one year. It had the Get Rich Slowly turtle logo on it, and I loved it. I started using the case.

Within two months, I had dropped and broken the phone. I got it repaired. A month later, I broke it again. I got it repaired. Then, a few months later, I broke it a third time while the case was on. WTF? So, I removed the case. It’s now been seven years since I took the case off, and I haven’t once damaged my phone.

So, I have fifteen years of case-less iPhone use with zero damage (despite a couple of drops) compared to nine months of cased iPhone use with three different costly repair bills. So, I go caseless.

That might change, though, depending on how the “Max” form factor feels to me. Will the larger size lead to more clumsy moments and/or drops? If so, I might get a case. But I doubt it.

I do other things that make me kind of a phone weirdo.

One simple but telling choice is that I don’t keep the Phone app in any sort of easy-to-access place. I tuck it into my app library. Why? Because I rarely make calls. When I do, it’s no issue to go find the Phone app. And when I receive calls, I don’t need the app; the incoming calls just appear on the screen, right? Kim thinks this is strange (she hates hunting for the Phone app on my phone), but I don’t care.

I’m also particular about how I arrange my apps.

I don’t like how cluttered Apple’s default grid-like layout looks, so I use various hacks to keep things de-cluttered. I use David Smith’s invisible home screen icon template to create “blank” spaces in my app layout. Like so:

![this layout comforts me [image of my phone app layout]](https://jdroth.com/wp-content/uploads/current-phone-layout.jpg)

On my previous phone, I also created substitute icons for the apps that lived on my home screen. I used the built-in Shortcuts app to create custom aliases to my most-used apps, then linked those aliases to new icons. I really really liked this because it slowed me down and forced me to think every time I went to use my phone. It was an instrument of mindfulness. But the downside is I didn’t like the launch sequence that Shortcuts has to go through to open the linked apps.

![good stuff, maynard! [image of my old phone app layout]](https://jdroth.com/wp-content/uploads/previous-phone-layout.jpg)

I’m considering doing this again with the new phone.

But probably my biggest piece of weirdness is that when I get a new phone, I don’t do the automatic migration. I know that doing so would save time, but I also feel like it leads to an accumulation of digital cruft. Unused apps remain on the device. Old settings stay without any sort of thought behind why I’m keeping them.

So, I set up every new device — phone, tablet, computer — manually.

Even doing this, there’s plenty that happens automatically. After all, much of my life lives in the cloud nowadays. All of my data is on Dropbox. Most of my settings are in iCloud. My passwords are also cloud based. So, a part of the setup process remains automated even when I do much of it manually.

Again, I do this because it forces me to mindfully evaluate which apps I’ve been using and which apps I want to use going forward. It’s like a forced digital housecleaning, and I like it…even if it does get a bit tedious for a few hours. To me, the tedium is worth it.

This year, there’s one final piece of weirdness to my phone setup. This year, I’m going to try to complete my divorce from the Google ecosystem. I will not sync my Google accounts to this phone. This may cause problems, but I hope not.

My concerns:

- In 2020, I moved from gmail to Hey. While I don’t love Hey 100%, I like it enough. Plus its methodology helps me maintain a clean inbox. Still, I do get important messages at gmail addresses from time to time. I’ll have to check gmail accounts via the web now and then.

- Similarly, I’ve moved from Google search to paid Kagi search. This is a newer change. I made the switch this summer, but I have zero regrets. I haven’t tried to set up Kagi on an iOS device yet, and I’m worried there might be barriers. Fingers crossed that it’s as easy as it should be.

- I haven’t yet broken up with Google calendars, and that’s a problem. Right now, I’m running a mixed system: Apple and Google combined. I don’t like it. So, one of my goals for the next month is to migrate completely to Apple calendars. I’m worried that I’ll miss something, though. So, I’ll keep Google calendars on my desktop computer for now.

- What about YouTube? As much as I’d like to not use YouTube (because it’s Google owned), there’s no real alternative. So, I use YouTube. And using YouTube requires a Google account. I might be able to use the YouTube app by manually entering my account data, but I doubt it. I’ll bet the app requires that I put my Google account on my phone.

My goal this year, then, is to discard as many of my four Google accounts as possible while setting up this phone. I should be able to discard three for sure, but it may be that I have to retain one (the one I use for YouTube and for commercial transactions). We’ll see.

There you have it: More than 1000 words about my weird phone use. It seems silly to write so much about it, but then this is the device I use more than any other, right? I use it all day long, and I use it all night long too. (As part of my sleep routine, I keep an audiobook playing throughout the night. This is probably why my phone batteries deteriorate so quickly.)

As is the case for many people, my phone has become my primary computer and communication device. It seems smart to spend some extra time thinking about how I set up and use it.

I am not a mechanical guy. Growing up, I was into computers not cars. I could build a computer for you, I could program it, I could diagnose problems, and so on — but I was hard pressed to figure out basic engine maintenance. My father did teach me to change the brake pads on my 1982 Datsun 310 GX, but that was about the extent of my car knowledge.

This hasn’t been a problem until now.

During the early stages of Covid — April 2020, to be precise — Kim and I bought an $850 shredder/chipper from Home Depot. Since everything was shut down, we figured we might as well use that time to do a bunch of yard work. And since we had a vast yard at that time, one filled with all sorts of trees (and their branches), it made sense to buy an expensive machine. We didn’t realize we’d be selling the house less than a year later.

We used that chipper/shredder a lot during the summer of 2020. In the fall, as we were working on our last pile of branches, the thing ran out of gas just as we were nearing the end of our work. “Great!” we said. “We don’t have to worry about draining the fuel!” We put the chipper/shredder away…and we haven’t thought about it sense.

This summer, we’ve been on a crusade to purge all of our Stuff. We held a successful garage sale last weekend, we’ve given things away, and we’ve made donations to Goodwill. We also want to sell the chipper/shredder.

Unfortunately, it will not start. Bummer.

I remembered that we’d run it out of gas, so I added fresh fuel. I expected the beast to start right up. It didn’t. I added oil. No dice. I bought a new spark plug and made sure the gap was correct. No luck. I replaced the air filter. Still nothing.

My neighbor across the street, Wade, is good with small engines. He does a lot of maintenance on his own equipment. He saw me struggling with the chipper/shredder, so he’s been helping me diagnose possible problems. He and his college-age daughter sit in the driveway and we play with possible solutions. None of them ever work.

Despite our failure to get the machine going, I’m having fun. I think that’s because I’m learning something new. I know nothing about engines, so all of this is like learning a new language. I’ve done a ton of googling, which leads to manuals to read and videos to watch.

This afternoon, the three of us made another attempt to start the engine. We were unsuccessful.

“At this point, I don’t know what’s wrong,” Wade said. “If it were me, though, I’d replace the carburetor. You can get them cheap on Amazon.”

It never would have occurred to me that I could replace a carburetor myself, but looking at the instructions it doesn’t seem difficult. And while the official part costs $65 at Amazon (and $84 from other sites), I can get a knock-off part for $16. I’m going to try that. (I asked Wade and he says he’s had mixed success using knock-off parts. “Read the reviews,” he said. The replacement I ordered gets good reviews.)

I’m skeptical that replacing this will work, but according to Wade there’s very little else that could be wrong here. Plus, it’s only $16 (and a bit of time) to give it a shot. That seems worth it to me. I’ll get to learn how to remove a carburetor and install a new one.

If this does work, I’ll immediately list the chipper/shredder for sale on Facebook Marketplace. If it doesn’t…well, I don’t know what I’ll do. I still might list it but for less. Or I might see if there’s a next step in the troubleshooting process (although Wade makes it sound like there really isn’t).

I’ve begun to think that maybe I should drain the fuel and add new stuff. The manual is clear that the fuel must be 87 octane with no more than 10% ethanol. I have no idea what kind of gas I put in. I probably got a gallon of premium, but it didn’t occur to me that I ought to be paying attention — so I didn’t. I could easily have bought a lesser fuel.

In any event, this is a fun learning project that’s occurring in s-l-o-w motion. It’s taken over a month to reach this point. Fingers crossed that it doesn’t take another month to solve the problem.

And after I’m done with the chipper/shredder? Well, then it’s time to sell my motorcycle…

One of my frequent complaints about us as Americans is that we have no real sense of history. We are very focused on the recent past and pay little mind to things that happened even forty or fifty years ago. This leads to some odd gaps in understanding and knowledge. People don’t grok how we got from Point A to Point B — and have no interest in learning — so when they see something from Point A in isolation, that thing seems offensive or weird.

I’m not immune to this behavior, of course. And perhaps it’s not a peculiarly American habit. Maybe it’s just part of being human. Maybe we’ve always been like this and always will be.

I’ve been thinking about this because last night I stumbled on one of my own blind spots.

The Path to Power

I’m currently listening to the The Path to Power, the first volume of Robert Caro’s highly-regarded biography of Lyndon B. Johnson. It’s a fascinating book and I can see why it’s so highly praised. I particularly like how Caro is unafraid to spent entire chapters (and dozens of pages) on digressions that provide context and color to the story. It’s entertaining, informative, and effective.

Midway through the book, for instance, Caro spends two entire chapters exploring the electrification of rural America, and particularly rural Texas. He opens chapter 27 with this bit:

Electricity had, of course, been an integral part of life in urban and much of small-town America for a generation and more, lighting its streets, powering the machinery of its factories, running its streetcars and trolleys, its elevated trains and subways, moving elevators and escalators in its stores, and cooling the stores with electric fans…It was not a part of life in the Hill Country.

Caro then spends pages and pages and pages describing what rural life was like without electricity: the grueling hours of work for men and women (and children), the monotonous repetition of chores necessary to obtain basic needs like water and heat, the endless work of food preservation, and the boredom of life without radio or electric light.

Life Before Electricity

Here’s a sample of the kind of effort that it took to simply live in rural Texas:

And so much water was needed! A federal study of nearly half a million farm families even then being conducted would show that, on the average, a person living on a farm used 40 gallons of water every day. Since the average farm family was five persons, the family used 200 gallons, or four-fifths of a ton, of water each day—73,000 gallons, or almost 300 tons, in a year. The study showed that, on the average, the well was located 253 feet from the house—and that to pump by hand and carry to the house 73,000 gallons of water a year would require someone to put in during that year 63 eight-hour days, and walk 1,750 miles.

Caro summarizes life for the rural farm family this way: “No radio; no movies; limited reading — little diversion between the hard day just past and the hard day just ahead.” (Aside: I’m curious why he uses semicolons in that sentence instead of commas. Is it the dash?)

Caro spends the entirety of chapter 27 describing what life on a rural farm was like during the mid 1930s. There’s zero mention of Lyndon B. Johnson at all. It’s simply pages of context and color. And the book is so much richer for it!

Electrifying Rural America

The next chapter delves into the politics behind electrifying rural America, and Johnson’s role in that process. At first, it’s the electric companies that refuse to to provide power to farms. To them, it’s bad business. It doesn’t make sense. They’ll never recoup the costs of building the infrastructure. Never. So, they refuse to do it.

When President Roosevelt established the Rural Electrification Administration on 11 May 1935, the tables turned. The government would help subsidize (and administer) the electrification of rural areas — but now it was the farmers who felt skeptical. Were the benefits of electricity really that great? And what about the costs? To them, electricity seemed outrageously expensive. How could they afford it?

The reluctance of the people sprang from simple poverty — “It cost five dollars [to apply for electricity], and a lot of people didn’t have five dollars,” says Guthrie Taylor. And it sprang from fear.

They were afraid of the wires. The idea of electricity — so unknown to them — terrified them. It was the same stuff as lightning; it sounded dangerous — what would happen to a child who put its hand on a wire? And what about their cows — their precious, irreplaceable few cows that represented so much of their total assets? “They were so worried,” Lucille O’Donnell recalls. “They would say, ‘What’ll happen if there’s a storm? The wires will fall down and kill [electrocute] the cattle.’”

It was a young Lyndon Johnson who helped champion the electrification of the Texas hill country (where he was from). He met with President Roosevelt and persuaded him to fund the project. In September 1938, the U.S. government did so. And about fifteen months later, electricity came to rural Texas.

Caro writes:

One evening in November, 1939, the Smiths were returning from Johnson City, where they had been attending a declamation contest, and as they neared their farmhouse, something was different.

“Oh my God,” her mother said. “The house is on fire!”

But as they got closer, they saw the light wasn’t fire. “No, Mama,” Evelyn said. “The lights are on.”

They were on all over the Hill Country. “And all over the Hill Country,” Stella Gliddon says, “people began to name their kids for Lyndon Johnson.”

These two chapters are a fascinating glimpse into a piece of American history that has largely been forgotten. We take electricity for granted nowadays. It’s difficult to imagine that less than 100 years ago, there were still large parts of this country that didn’t have it.

The Electrification Acceleration

In 1935, when the Rural Electrification Administration was created, about 85% of city homes had electricity — but only 10% of farms did. This graph from the U.S. Census Bureau shows that much progress was made in ten years, despite the outbreak of World War II. By 1945, about 40% of farms had been electrified (compared to about 90% of city homes). And in 1955, the gap had closed to almost zero: about 95% of all homes in the U.S. had access to electricity.

![the progress of rural electrification [graph showing share of U.S. residences with electricity]](https://jdroth.com/wp-content/uploads/rural-electrification.jpeg)

But even that last fact kind of boggles my mind. Less than fifteen years before I was born (in 1969), there were still 5% of U.S. homes without electrical power!

I’m fond of doing historical comparisons to gain perspectives on timespans. Let me give you an example. Thirty years before I was born — in 1939 — there were still 15% of city homes and nearly 90% of farms without electricity.

Now, to gain perspective, think about thirty years before today. It’s 2023. What will kids born this year look back on and think “wow, I can’t believe this is such a recent technology”. Maybe it’s the internet? That’s not a perfect example but it’s close. I’m not sure their was a rural/urban divide in internet adoption, but it’s a technology that probably had around 10% use in 1993 (or maybe 1994 or 1995, not sure), but now is nearly ubiquitous.

Anyhow, I’m starting to ramble.

Final Thoughts

I enjoyed these two chapters from The Path to Power so much that I read them twice. Then I read them a third time while writing this article. It makes me realize that I haven’t been paying near enough attention to this book, so I’ve purchased a copy for Kindle and plan to read it in print in addition (simultaneously?) to listening to it.

Most of all, I can see why people praise Robert Caro. Can you imagine making the Rural Electrification Administration interesting? Yet he does. In this two-chapter digression from the story of Lyndon B. Johnson, Caro paints a clear picture of what life was like in the mid 1930s and why Johnson became a powerful political figure. And yet Johnson barely figures into the text for these 27 pages.

Footnote: I know little about Lyndon B. Johnson and didn’t choose this book because I wanted to learn about him. I chose this book because again and again I see people praising Robert Caro’s writing, and I wanted to experience it. The Path to Power is the first of four volumes in Caro’s biography of Johnson. For more than a decade, Caro has been working on a fifth and final volume. He says he has ~630 manuscript pages but still isn’t anywhere near finishing. He’s 87. I hope he’s in good health, because I look forward to reading all five volumes of this biography.

For two years now, I’ve been talking about taking art classes. I want to learn how to draw and/or work with watercolors. I’m dabbled with both a tiny bit in my free time, but I’m not so good at being self-directed. I’m much better when somebody imposes structure on me, especially when it comes to study. (Left to my own devices, my ADHD takes over and I flit from one thing to the next.)

I’ve been talking about taking art classes, but I haven’t actually taken any. Why not? Mostly it’s because I’m scared. Not scared as in “oh my god I’m going to die!”, but scared as in “trying something new that’s a bit uncomfortable”. Why am I scared? I have no idea. It’s not rational. It’s just how I operate. Starting new things can be tough for me.

Anyhow, I finally overcame my trepidation about a month ago, and I signed up for two art classes at the local community center: Realistic Drawing on Monday mornings, plus Ink Pen + Watercolor on Tuesday evenings. I’ve been super excited about finally making this leap. Go me!

I gathered all the class materials and set them in two piles on the kitchen table. They’ve been waiting there for an entire month, reminding me that I’m about to learn how to do art.

![My art supplies, waiting patiently to be used [photo of my art supplies]](https://jdroth.com/wp-content/uploads/art-supplies.jpg)

Then last week, the community center called to let me know that the Ink Pen + Watercolor class had been cancelled due to low enrollment. I was sad, but at least I had the Realistic Drawing class on my schedule still.

Well, just a few minutes ago the community center called to say that class had been cancelled due to low enrollment also.

This is all funny in a sad sort of way. After waiting so long to register for art classes, I finally took action — only to have my action nullified. Haha.

I’m not going to let this stop me, though. I already have it in my head that I’m taking art classes this autumn, so I’m going to check out the website for the local community college. I’ll bet there are some similar options (although they’re probably more expensive).

As I re-adjust to writing at Folded Space once more, I’m struggling to know what qualifies as “worth sharing” and what doesn’t.

In the olden days, I’d simply sit down and jot a note about whatever was going on in my life — or whatever silly things was tickling my brain at the moment.

But during nearly 20 years of writing at Get Rich Slowly, I became much more selective about what I published. I spent much longer on the articles I wrote, and I carefully considered what was worth sharing. (I never actually published about half the stuff I finished. And I only finished about half of the articles I started.)

Obviously, I’ve been erring on the side of “share longer, more interesting things” here. But a part of me hates this. It’s putting a filter on myself.

So, I’m going to make an effort to share a lot of little stuff for a while. I’m not sure how successful I’ll be, but I’m going to try. And I’m starting right now! I’m going to share one of my favorite websites.

MetaFilter

The internet community I’ve been a member of longest is MetaFilter. I joined the site on 09 August 2002 (although I had been reading it since it started), and I’ve been mostly active ever since.

MetaFilter is a “community weblog”. Think of it as a proto-Reddit. There are no sub-sites for different topics (although there are broader divisions I’ll explain in a moment); everything is posted to the main “stream”. Comments aren’t threaded, but you can “favorite” the stuff you like most. It’s all very very 1999, and to me that’s a lot of the appeal. It’s lo-fi and I love it.

MetaFilter has a handful of subsections.

- There’s a Projects subsite where users can share the cool things they’re working on. (It’s also where I first announced Get Rich Slowly!)

- There’s a seldom-used Jobs section where mefites can hire other mefites to work for them.

- There’s a Music section for creators to post their songs.

- There’s a fairly active section called FanFare where mefites geek out about their favorite media.

- Best of all, there’s a section called Ask MetaFilter where you can recruit the “hivemind” to help solve your problems. Or to comment on them, anyhow.

In recent years, the main MetaFilter site — “the blue” — has become increasingly politicized. Posts and conversations are decidedly left-leaning. Opposing viewpoints are not tolerated. I happen to lean left myself, but I find MetaFilter currently to be a dogmatic echo chamber that’s sort of a parody of modern self-congratulatory liberalism. I read it less and less with each passing month.

Ask MetaFilter

But AskMetafilter? AskMetafilter remains great. Sure, the userbase is the same as the main site (so there’s plenty of politicalization that occurs), but AskMe is still largely a gorgeous, chaotic mess of questions and answers about all sorts of stuff. It’s a pleasure to peruse.

(As an aside, AskMetafilter is the source of one of my favorite mental frameworks: Ask Culture vs. Guess Culture. It’s a way of looking at how people relate to each other and why sometimes conflicts arise. I come from a “Guess Culture” family where we don’t explicitly ask for what we want. This causes me no end of headaches.)

Here are some examples of recent AskMe questions I found interesting:

- How do I handle a romantic connection with somebody ten years younger than me?

- What songs sound like the 1990s felt?

- What are your life-changing laundry tips?

- What books broke your brain?

- I’m 34, female, and feel like I’m a decade behind in life. How do I deal with this?

- How can I cope with feeling lonely in the evening?

But here’s the real reason I’m writing about AskMetafilter today.

The Best of Ask MetaFilter

This morning, I found myself scrolling through the site’s all-time most popular questions. While the vast majority of questions at AskMe get maybe ten to twenty responses (and a handful of “likes”), these questions have hundreds of answers and, in some cases, thousands of likes. This list is going to give me reading material for the next couple of nights. And it’s going to give you reading material for the next hour or so haha.

Here are some gems:

- Should I pay to replace a rude guest’s shawl? [Trust me: Reading this question and its responses are worth your time. People are strange.]

- A party guest destroyed my gift. Party foul or reason for jihad?

- What purchase was worth every penny?

- What experience mostly shaped who you are?

- Did my boyfriend just get married?

- How do I go barefoot at work without detection?

Those are just a few examples. There are many more.

Ask MetaFilter is my favorite website, and it has been for a long time. Something about it has a perfect balance for me. There’s enough new stuff (maybe 20 posts a day?) without being overwhelming. The questions and answers are diverse and interesting. People are genuinely trying to be helpful. The quality of responses is far superior to the stupid shit I see on Reddit. And so on. For nearly two decades, Ask MetaFilter has been a daily read for me.

The Lo-Fi Web

Anyhow, here’s my MetaFilter profile (which could use some updating!). Here are my AskMe questions and my AskMe answers. Really, though, I think you get a good glimpse into my interests by looking at the posts and comments from others that I’ve favorited over time.

Related: As time goes by, I find myself drawn more and more to what I call “the lo-fi web”. MetaFilter is an example of this. I’ll certainly write more about the lo-fi web in the future. (I just excised three tangential paragraphs about it from this post!) If you’re interested in the meantime, check out two articles: “The Small Web Is Beautiful” and “The Lo-Fi Manifesto”. Neither of these perfectly encapsulate what I mean by the lo-fi web, but they both come close. I’ve just ordered (but have not yet read) Cory Doctorow’s new book, The Internet Con: How to Seize the Means of Computation, which promises to explore similar ideas.

For a long time now, I’ve embraced the Zen concept of shoshin (or beginner’s mind). The notion is simple. When approaching any subject, do so with the openness and enthusiasm of a novice, leaving aside preconceptions and prejudices. Basically, forget what you know — or think you know — and start from the beginning.

I’ve been reminded of this notion while working on my project to interpret (not translate but interpret) the Tao Te Ching for my own personal benefit. The Tao often uses children and newborn as metaphors. But this morning I got a stark lesson in the need for beginner’s mind in real life.

This year, I’ve been focused on fitness. In the past when I’ve tried to get fit, I’ve been overly attuned to my weight. As a result, I lose weight but struggle to keep it off. I reach my goal (usually about 170 pounds) then, because I don’t have a new goal, I gradually regain all that I’d lost. My problem, I know, is that I’m too centered on the results instead of building good habits. (This is similar to folks who get out of debt but can’t stay out of debt because they focused on the outcome rather than the process.)

So, while I’m certainly tracking outcomes this year, they’re not where my attention has been directed. Instead, I’ve been teaching myself to make smart choices with regards to food and fitness. I’m losing weight much more slowly than past efforts. Three times in my life, I’ve lost 50 pounds in six months. Right now, I’m down only 25 pounds in nine months. The difference, though, is that nothing I’ve done feels onerous. I’m not starving myself. I’m not working out like a maniac. I’ve made small changes that feel natural to me, and I’ve never felt deprived.

My exercise has largely consisted of two activities: lifting weights and walking.

I love to walk, so it hasn’t taken a lot of willpower to do more of it. I’ve simply elected to walk when normally I might drive. I walk the 0.9 miles to the grocery store, for instance, or the 2.7 miles to downtown Corvallis. I don’t do this every time — I won’t do it when I run errands today, for instance — but when time, weather, and mood allow, I make it a priority.

I don’t love lifting weights, but I do love the results. Lifting makes me feel strong and confident. But lifting is hard. It’s difficult. It takes effort. Sometimes it’s frustrating. Still, I’ve put in that effort and I’ve enjoyed great results. It took me six months to reach a level of strength that required two years of progress back in 2011-2013. It pleased me to no end that at age 54 I could match (and sometimes beat!) personal bests I’d set at age 44.

But the problem with lifting is that it’s hard on my body. The squats hurt my knees. (In theory, they shouldn’t hurt if I have good form. In reality, even when I’m laser-focused on form, the knees still hurt.) Any kind of overhead press — military press, bench press, whatever — hurts my shoulders. Pull-ups hurt my shoulders. Push-ups hurt my shoulders. Lunges really hurt my knees.

I want to lift weights, but I feel like I need to take a break and find some other fitness activity that is less stressful on my body.

Enter swimming.

Our gym has two pools. One is a small, warm pool for water aerobics classes. The other is a 25-yard, five-lane lap pool. They both get plenty of use from members.

I don’t mind swimming, but I tend to hesitate making it part of a fitness program. I know that it’s a difficult, frustrating experience when done for exercise and not for fun. Back in 1997, when I first lost a bunch of weight, I made swimming a regular part of my workouts once I’d reached 170 pounds. And that’s part of the mental barrier I currently have. I’m at 190 pounds and feel like I’m twenty pounds away from being able to swim.

To me, swimming is the peak exercise activity. It’s as if there’s a pyramid of exercise based on difficulty and fitness. At the bottom is walking, which is generally easy for everyone. (I’m old enough now to realize that some folks struggle with it, but for most people it’s the base of the exercise pyramid.) Above walking are stretching exercises and yoga. Above those are weight lifting. Above lifting is running. And above running is swimming. (This is my personal exercise pyramid; yours might be different.)

Because I have this mental construct, I tend to put off trying to swim until I’m near peak fitness. I’ve been doing that all year. Kim has been prodding me to swim, but I’ve been resisting. “I’ll swim once I’m below 180,” I tell her. Or, “I can’t swim until I can run a 5k without resting.” Stuff like that.

This is silly, right? Especially now that I’ve realized my knees and shoulders are in shoddy shape. If I think swimming will benefit me — and it will — then I need to go swim.

So, this morning that’s what I did. I got up at 6:30, like I always do, and I went to the gym. I told myself that even if all I did was familiarize myself with the swimming facilities, that’d be a win. And that’s what I did.

I walked around and looked at the pools. I felt the water temperature. I checked out the hot tubs. I went into the steam room. And then, since I was already there, I got in the pool and I swam. (This is a trick that I’ve learned: If I tell myself that all I have to do is go to the gym to succeed for the day, I’ll usually do some exercise once I’m there.)

I didn’t swim far. In fact, I only swam four laps (or 100 yards). But I swam. And I would have done more but man oh man, my form sucks. I remember now that when I was swimming 25 years ago, it took me a long time to figure out proper breathing and form. At first, I felt like I was flailing around. And I struggled to catch my breath. Well, the same was true today. Perhaps more so. My first two laps were okay, but the last two were crazy hard.

I’m not discouraged, though. Instead, I’m practicing shoshin, beginner’s mind. I swam four laps today. I’ll swim six laps tomorrow. And before I swim those six laps, I will read (and watch videos) about proper form and breathing. I will be patient. I will forget what I know (or think I know) and learn from scratch. I will practice. And in time — probably less time than I think — I’ll be able to swim greater distances.

On my way out this morning, I stopped at the front desk to leave a note for the gym’s swimming instructor. I asked her if she’d consider giving private adult swim lessons for a fee. I think it’d benefit me to take three or four classes with somebody so that I could get the basics down.

It may be that this is just a temporary whim, but I hope not. I feel like swimming could be a beneficial tool in my exercise arsenal. It could, especially, be an important skill as I grow older. I want to learn how to swim effectively, and to do that I need to forget what I know and adopt a beginner’s mind.

Fair warning. This post is J.D. ranting about something few people care about: the climate and weather of Portland, Oregon. If that sounds boring to you, you might want to skip this haha.

My buddy Douglas writes one of my favorite newsletters at Substack: Money and Meaning. It’s great stuff, filled with deep insights on what makes humans tick. Today, in a piece entitled “We Are Climate Change”, Douglas wrote:

In the last week, as I’ve been writing this, Portland endured 3 straight days of over 100F. In 2006, when I moved here, the city might get to 90F once or twice a year. Talking to people who grew up here, anything in the mid 80s was a hot day.

All summer, I’ve been seeing similar claims around the interwebs. These claims bug me because I think they’re wrong. These temperatures are not unusual. They’re the norm during Portland summers, and they have been all of my life.

First of all, these claims seem wrong on a gut level. This is my 55th summer in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, and nearly all of them have been hot. Temps over 90 don’t seem rare. And temps in the eighties seem common. I’ve never considered 80 or 85 to be hot. These, to me, are normal summer temperatures.

That’s my view anecdotally, but what do the official records say? Well, the official records back me up.

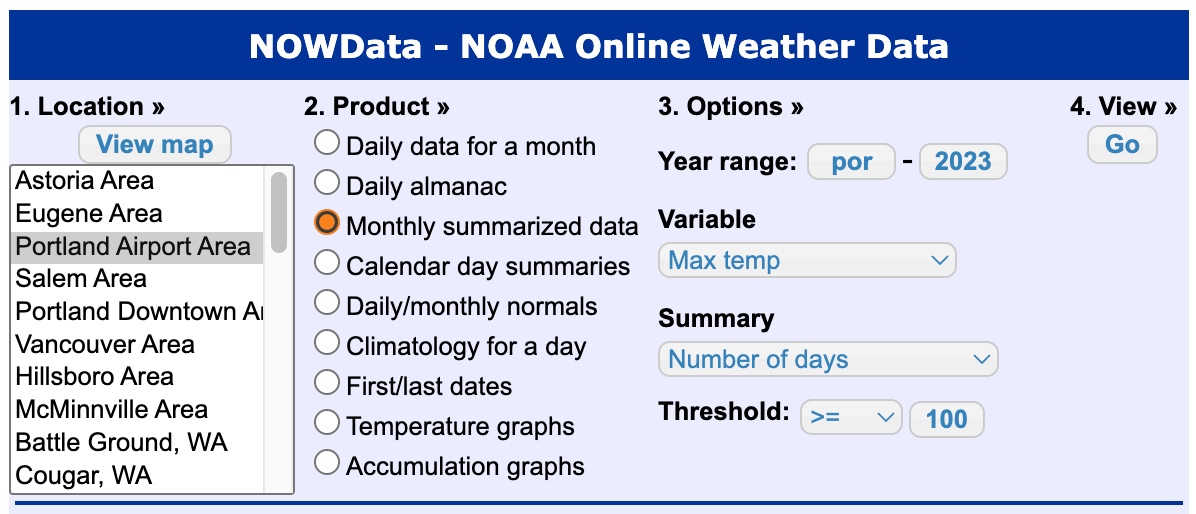

For 20+ years now, I’ve been a fan of the National Weather Service website. It’s chock full of great statistics and official data. The site’s navigational system is a little wonky, but once you get used to it you can find all sorts of cool info. For Portland (and all of Oregon, I think), the page you want is this one, the climate page.

If you explore the five subsections (NOWData, Observed Weather, Climate Prediction and Variability, Local Data/Records, Climate Resources), you can find just about anything you want to know about the local climate. This is true for Oregon, and I suspect it’s true for all other U.S. states.

If you want it, you can download a comma-delimited file filled with all past recorded data to import into a spreadsheet. But what I find really useful is each city’s climate book. (Here’s the Portland Climate Book.) These publications — and their web-based counterparts — process the data in lots of interesting ways: monthly maximum temps, top 10 warmest days (by month), wettest seasons, first and last snowfall (Portland averages four days per year with measurable snowfall), days with fog, etc.

All of this is to say: There’s a lot of weather data out there for folks who want it. Which brings me back to my complaint. All summer, I’ve been seeing/hearing people claim that Portland never used to get this hot. And that’s just not true.

I used the National Weather Service website to dig up some data. From the NOWData tab on the Portland climate page, I generated some custom reports. Here, for instance, is how I looked up how often Portland reaches temperatures over 100 degrees.

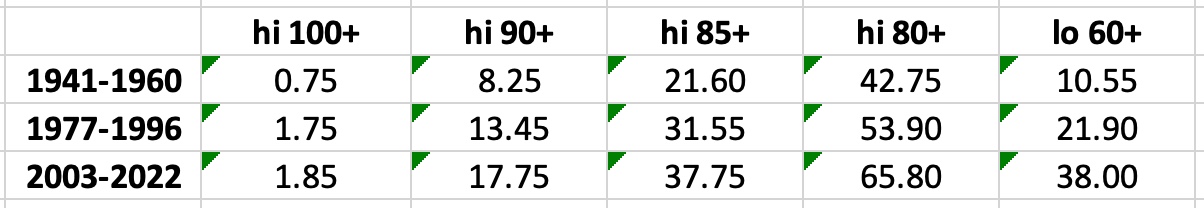

Here are the results of my number-crunching:

- From 1941 to 2022 (which is 82 separate years), Portland experienced a high temperature over 100 degrees in 47 different years — or 57% of all years. We had 101 days reach this high during those 82 years — or just over once per year. (During the two decades from 1977 to 1996, we had 100-degree days in sixteen of those years. Basically, 100-degree days happened almost annually during my formative years.)

- From 1941 to 2022, Portland experienced a high temperature over 90 degrees every year except 1954. We had 1018 days reach this high during those 82 years — about 12.5 times per year.

- From 1941 to 2022, Portland experienced a high temperature over 85 degrees every single year (although 1954 only had one — why was it so cool?). The area averages thirty days over 85 each year. That’s an entire month! If you were to ask me what the average high in Portland is during the summer, I’d tell you 85 because that’s what I’ve always believed.

- From 1941 to 2022, Portland averaged nearly 54 days per year with highs over 80 degrees. Even in the strange, cool year of 1954, the area had ten days over this temp.

Basically, these numbers back up my memories. Portland has always experienced these kinds of temperatures. They’re not new and they’ve never been uncommon.

Now, having said all that, although I disagree with folks on specifics when they claim that Portland didn’t see these temperatures in the past, I agree with their broader overall points. Climate change is occurring. While high temps like this aren’t new for Portland, the frequency with which we reach them is clearly increasing. Most people recognize that climate change is a reality, and for good reason.

(One of my favorite anecdotes from our cross-country RV trip: Kim and I were stranded in Plankinton, South Dakota in July 2015 when our RV engine blew up. We spent ten days hanging out with the local farmers. It was fun! They were a very conservative bunch with stereotypically conservative views — except that every single one of them admitted climate change was happening. They experienced it daily in their crops and harvests.)

There are better ways for people to talk about the changes to Portland’s weather. They start with actual data. Here’s a summary table, for instance, that shows the actual change in the number of days above certain temperatures for the Portland area over 20-year periods.

During the twenty years between 1941 and 1960, Portland averaged about 22 days over 85 degrees each year. In my formative years (from 1977 to 1996), we averaged about 32 days over 85 degrees. And over the most recent 20-year span, we’ve averaged 38 days over 85 degrees. There is a trend here, for sure.

As an area native, it’s not the summer highs that seem unusual to me. No, it’s the summer low temperatures. My memory is that our summer nights used to be much cooler. In recent years, it stays much warmer overnight, which makes sleeping more uncomfortable. This is the change that seems most pronounced to me.

Again, the data backs me up. You can see that we now have 38 nights each year where the temp stays at 60 or more. This is way up from the past.

I’ve wasted a crazy amount of time this afternoon — and written a stupid number of words — because I care about these sorts of claims and statistics. I agree that climate change is happening, but it’s careless to use anecdata to back up claims better supported by actual data. Anecdata harms an argument rather than helping it.

(Sidenote: A bigger pet peeve is the common claim among Oregonians that “it always rains on Independence Day”. Grrrrrr. But I’ve written about this before, so I won’t belabor it now. Let’s just say it’s unusual to have measurable precipitation on July 4th, and it’s rare to have any real rainfall.)

I have regularly scheduled video chats with a handful of friends. Also, irregularly scheduled chats with other friends. This is a new-ish thing in my life — only in the past five years — but I’m under the impression that it’s becoming more and more common for more and more people. (Kim does this too with three different groups of people.)

Anyhow, I had my monthly call with Mary this morning. (Name changed because I didn’t ask her permission to include what follows.) Our calls are funny/interesting because they nearly always seem to be therapy sessions for one or the other of us. Or both of us.

Mary and I share similar traits. We’re perfectionists. We procrastinate. We’re easily overwhelmed. We do excellent work when we do our work, but too much of the time we simply avoid what we have to do.

Earlier this year, I was the one needed support, and Mary was excellent at providing that. During our chats, I’d complain about my lack of motivation or my existential angst, and she’d offer practical suggestions and recommend books to read. Waking Up. The Untethered Soul. Lost Connections. The Body Keeps the Score.

Today, though, it was Mary’s turn to be in the pit of despair.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with me,” she said at the start of our call. “I stay in bed all day scrolling TikTok. I don’t know why I do it. It’s boring! Yet I cannot stop myself. It’s beginning to affect my relationship.”

I offered advice, of course, but it was all stuff Mary has heard a million times before. One of the problems she and I have is that we know intellectually how to deal with this shit — yet we struggle to put the habits into practice. I said as much during our call today.

“Yeah, I do know what’s supposed to help,” Mary said. “Exercise. Socializing. Being in nature. Eating right. I know all of this. But you know what? Even when I do these things, I don’t get much relief. I’m still stuck in this funk.”

“Do you have anyone local you can talk with about this?” I asked.

“Sure,” she said. “But I think that’s part of the problem. I talk about this too much! It’s like I’m wallowing in it. And, of course, I’ve talked with therapists about my issues. I’ve probably seen a dozen therapists, and none of them has ever been able to help.”

“Do you think any of what you’re experiencing is existential dread?” I asked. “I know some people feel swamped by the state of modern life. For me, all of my experiences with death recently put me in a place where life seemed so meaningless. I kept wondering what is the point of it all? That’s what put me in a dark place last year: a meaningless universe. And using too much marijuana.”

“No, I don’t think that’s it for me,” said Mary. “I don’t know what it is. Part of it is that life is so relentless. I don’t have energy to deal with the constant onslaught. What’s the point of doing anything because there’s just going to be more stuff to do later.”

“I know what you mean,” I said. “I feel the same way. It’s like when you get to Inbox Zero, right? Yesterday, I managed to get my email inboxes empty. Let’s see how many messages I have now. There are ten on this account and twenty on the other one. What’s the point? I’m never going to catch up. And that’s how I feel about my to-do list.”

I held up one of my several to-do lists for Mary to see. “If I cross off three things today, more things will crop up to replace them. So, I end up not doing anything that isn’t urgent.”

“Exactly,” Mary said.

“See here? I have ‘sell motorcycle’ on my list. It’s been two years since we moved to Corvallis. I haven’t ridden my motorcycle in those two years. And I’ve known the entire time I need to sell it. But I don’t do it. It seems like so much work. It’s such a hassle. So, it just sits in the driveway, a constant reminder that I haven’t crossed it off my list.”

I told Mary about my recent exploration of taoism and zen buddhism. “I’m not into them for the spiritual stuff — if there is spiritual stuff. I’m in them for the mindset. I’ve found it really helpful. Instead of beating myself up for not getting things done, I just accept it. All the same, I sometimes wonder what would happen if I spent a month of focused energy to cross everything off my lists. Would I feel relief? Would the lists stay empty? Would I be able to keep up with new tasks so that the backlog never built up again? I suspect that I’d just come up with dozens of other things that needed to be done.”

We talked some about the past. Is this feeling of overwhelm a modern thing? Did American pioneers experience existential dread? Did they procrastinate? Did they struggle with mental health? Much has been made about how mental health issues are a modern phenomenon, but I’m skeptical. I think humans — and other animals — have always struggled with anxiety and depression. It’s just that nowadays we have a vocabulary to talk about these things.

“You and I are a fine mess,” I said to Mary near the end of our call. “Yet we keep muddling through. Life is both joyous and frustrating, isn’t it?”

“It is,” she said. “It is.”

I feel fortunate that my own mental health struggles have been minimal this year. This is largely because I’ve given myself permission to put myself first. But it’s also because I’ve become proactive. I’m taking Wellbutrin. I’m reading zen/taoist stuff daily, even if it’s just a couple of pages. I’m trying to reduce my use of alcohol and pot. And when I sense an episode coming on, I take action.

Over the past week, for instance, I’ve felt myself sliding into a funk. Yesterday was the first time since May that I truly felt blue. I got nothing done. But instead of beating myself up, I simply acknowledged that I felt shitty and let myself sit with it. By not wallowing in the funk, it didn’t spiral out of control. I feel better today.

But I’m going to continue to put into practice the things that I know have been proven to help me. I’m taking a break from mind-altering substances. I’m going to the gym. And as soon as I edit and publish this piece, I’ll grab the dog and we’ll take a two-hour walk. I’ve learned that few things feel better than allowing my beagle to lead me through town as she sniff sniff sniffs all of the amazing smells.

(p.s. Here’s something that pleases me. As I get back into the groove here at Foldedspace, I want to remember to write more. When the spirit moves me, I want to stop, write, and publish — without belaboring perfection. I’ve gotten out of the habit. After my call with Mary, I deliberately made thirty minutes to get this all out of my head. Yay!)

Kim and I are currently in the process of estate planning. We both completed simple wills about a decade ago, but things have changed. And now that we’re older we’re trying to get more sophisticated with our plans. We’re establishing a trust. We’re creating advance directives for healthcare. Et cetera.

This is proving much more difficult for me than I’d expected. I don’t want to think about some of these things. Completing a will? No problem. But thinking any farther than that is proving problematic.

I can now see how my cousin Nick felt. In February 2022, when it became clear that he had only weeks to live, I had to pester him and pester him to complete his will. He didn’t want to do it. He told me that thinking about it felt like an admission that death was imminent. Things were complicated too by his indecisiveness. I went with him to notarize one version of his will, which — fortunately — he revoked and replaced. There may have been other versions.

Now I’m experiencing similar indecision, and sometimes about basic things!

Take beneficiaries, for instance. Designating a primary beneficiary is non-difficult. If I die before Kim, she gets my stuff. But what happens if we die together? Or what happens if she dies first? It would be easy if either of us had children. But we don’t.

Should I designate my brothers as secondary beneficiaries? My nieces and nephews? Kim’s nieces and nephews? My ex-wife? My college? A charitable organization?

On some level, it doesn’t really matter. If I’m dead, I don’t care who gets my stuff. Yet at the same time I know I have a chance to improve the world in some fashion. I ought to do that.

This decision — which should be stupidly simple — has kept me stymied for a week. I’m not joking. My gut tells me to designate Kris as my secondary beneficiary. I spent 23 years with her and she knows me better than anyone besides Kim. But she has plenty. And isn’t it a little weird to leave your estate to an ex? I don’t know.

It’s also tough to answer some of the questions on the advance directive. What if I’m in a vegetative state? No extraordinary measures, I guess, although it feels like I’m betraying my future self in a way. What if I’m terminal, like my cousin Nick was, and likely to die in a couple of months? Nick wanted all available treatments to sustain his life but it didn’t make a bit of difference in the end. The cancer was going to kill him no matter what. Would I want to fight like he did? Or would I rather say, “Drug me up. Turn on some anime. Let me drift away.”

And who do I want as my secondary (and tertiary!) health-care representative? Again, Kim is first. But who is second? My brothers? My ex-wife? Honestly, I trust Kris more than anyone…but I also don’t want to saddle her with this sort of thing. (In this case, the health-care representatives must sign off that they agree to take the responsibility, so this will remove part of the dilemma.)

What about our animals? For us, our pets are very much like children. I know, I know: Many people find this annoying. So what? It’s just how it is for us. If Kim and I were both gone, we’d want our beasts — especially the dog — to have good homes.

All of this is to say: I see now why so many people put off planning for death. Nobody wants to think about their own demise, of course, but it’s also tough to answer some of the questions. At what point do I want doctors to stop trying to save me? Who do I want to get my stuff? Who do I want to make decisions for me if Kim isn’t there to do it?

I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know. At least by writing about it I’ve been able to delay making decisions by half an hour…

Yesterday morning, Kim and I set out to stain the new fence in our back yard. We spent a comical 90 minutes attempting to use a pump sprayer to make the job easier, but we gave up after a frustrating series of problems. Instead, we resorted to good old-fashioned rollers.

We managed to stain about one-third of the fence before we both decided to call it a day. We went inside to watch movies instead. It was my turn to pick something.

“What do you want to watch?” Kim asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Something Asian. Or something disturbing. Preferably something Asian disturbing.”

Left to my own devices, I watch a lot of Asian films. (And yes, I know that’s a very broad umbrella.) I’m particularly partial to Japanese classics. Recently, I’ve discovered I enjoy disturbing movies too. I have no idea why, but I do. I realized this after watching Ari Aster’s very disturbing Midsommar during my prep for seeing Barbie in the theater.

Ultimately, Kim and I did not watch a disturbing movie together. We compromised on a film that was neither Asian nor disturbing: the surprisingly amusing Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. I won’t say it’s high art, but it was fun.

Later, though, I indulged my desire for “Asian disturbing” alone. I watched Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance from Park Chan-wook. That’s exactly what I was looking for!

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance is beautifully filmed. It is also very Asian and very disturbing. This shouldn’t be surprising, I guess, since it’s from the same mind that gave us The Handmaiden. I want to see more from Park Chan-wook. (I have Oldboy on DVD coming this week, and I bought “Decision to Leave” in the iTunes store last night.)

Since I started logging my films in Letterboxd on 01 January 2021, I’ve seen 220 movies. I’ve tagged 13 of those as “disturbing”. By this I mean that, for whatever reason, I found them unsettling at the time I watched them. (This could be for a variety of reasons.)

Here are those films in chronological order of their theatrical release date:

![Thirteen disturbing films [Thirteen disturbing films]](https://jdroth.com/wp-content/uploads/disturbing-films.jpg)

Like I said, I’m in the mood for movies like this right now (I have no idea why haha). I’m especially in the mood for the “Asian disturbing” subgenre. Those movies are just so inventive and twisted! In the coming weeks, I intend to watch (or re-watch):

- Zhang Yimou (To Live, Raise the Red Lantern)

- Chen Kaige (Farewell My Concubine, my first exposure to “Asian disturbing” thirty years ago)

- Park Chan-Wook (Oldboy, The Handmaiden, Decision to Leave)

- Bong Joon-ho (Parasite)

- And others I’m sure I’ll find along the way.

I also want to have Kim watch Ari Aster’s Midsommar with me. Then, I want to watch his Hereditary, which I have not yet seen (but which I believe to be even more disturbing than Midsommar). Denis Villeneuve might be my favorite filmmaker at the moment, and he has some excellent disturbing films, including the alarming Incendies.

Villeneuve’s Polytechnique and Sicario are also on my list.

Anyhow, if you have recommendations for other good disturbing films, let me know. I’m not looking for stuff that’s gross-out for the sake of being gross-out. I’m more interested in movies that are genuinely psychologically disturbing. Incendies is probably the best example of this. It might be the most disturbing movie I’ve ever watched, but there aren’t any gross-out moments.