“My generation doesn’t know how to be thrifty,” writes Eve Conant in the current issue of Newsweek. She describes how her grandfather — who fled his native Ukraine during World War II — would store plastic bags filled with leftover bread crusts in the closet of his new home in California, a house he bought with $13,000 cash. “He couldn’t shake old habits,” Conant writes. “Or were they old virtues?”

Now, many decades after Arkady’s arrival, I also have plastic bags in my closet. But they’re filled with nice clothes I’m giving away because my wardrobe is too full. The biggest life issue facing me when I open my closet door is whether to put on an Ann Taylor jacket or a Gap sweater. As talk of recession and belt-tightening makes headlines, I wonder where and how I lost my grandfather’s sense of thrift.

These sentiments aren’t exactly new. For decades — centuries, even — people have complained that younger generations haven’t inherited the financial wisdom of their elders. During the 1750s, Benjamin Franklin bemoaned the lack of money skills among the American colonists. But these warnings took on greater urgency with the dawn of the age of easy credit. In the introduction to Ain’t We Got Fun?, Barbara Solomon writes:

Prior to the 1920s the public had held generally negative attitudes toward credit purchasing. Young people were warned against burdening themselves with a lifetime of debt and were made fearful of losing their possessions should they fail to make payments on time. In the Twenties all that was turned around.

Advertisers promised an acquisitive public that it needed no money down and could get liberal terms. Millions of ready buyers were convinced that there was no need to deprive themselves of the magnificent new appliances and machines of this age of progress. In 1927 six billion dollars’ worth of goods (about 15 percent of all sales) were bought on installment plans. And the factories kept on producing more merchandise.

The general sense of prosperity, coupled with the disillusionment of wartime idealism, became the basis of a new theme that dominated the age. The mass of Americans believed that they had an inalienable right to the good life and particularly to “a good time”. And a good time they determined to have.

Never before had a generation set out to be so self-consciously different from their forebears.

What had been one of American history’s recurring motifs now became a primary theme. Attitudes toward money, debt, and credit actually did begin to change. During the next several decades, the use of credit lost its stigma; it became an accepted — even celebrated — way of life.

In Conant’s Newsweek article (which I recommend highly), the author worries that this lifestyle of debt has made her generation ill-equipped to handle financial hardship. “How often do the words ‘frugal’ or ‘thrifty’ come up in conversation, especially as a compliment?” she wonders. From her story:

“People in their 30s haven’t really experienced a significant or long recessionary period,” says consumer behaviorist Larry Compeau of Clarkson University. “I am concerned that they won’t be able to respond quickly enough to mitigate what may be the damage ahead. Not only do people under 40 save less, but they have less to save.“

My worry is not that we’re saving less, it’s that we’re no longer saving at all. The personal saving rate in the United States has been declining for years. In the 1970s and early 1980s, it frequently climbed above ten percent. More recently, it has hovered around zero. But the general trend is downward. Americans are not saving.

The personal saving rate began to drop in the mid-1980s. A 2002 publication [PDF] from the Federal Reserve Board of San Francisco notes three possible causes:

- The “wealth effect”: When people become richer (or perceive themselves to become richer), they spend more.

- Americans have become more productive and are, in general, earning higher wages. If they believe these increased incomes are likely to continue, they’re willing to spend more because they believe they’ll have money in the future.

- Easy access to credit. Though the first major credit card was created in 1958, and use grew in the sixties and seventies, credit cards didn’t play a prominent role in American life until the 1980s.

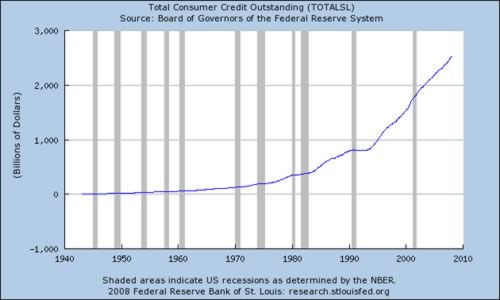

Though the Federal Reserve Board believes consumer credit plays some part in the low saving rate, it isn’t considered a primary factor. I’m not convinced. The total level of consumer credit outstanding has waxed even as the saving rate has waned. I realize that correlation does not imply causation, but I’d love to see more information about how the following graph relates to the first:

What does all this mean? Does it matter to you and me? Is the subprime debacle related to personal saving at all? Could the stock market collapse? Will the credit industry implode? And what happens if the worst comes to pass?

I don’t know.

The financial picture seems bleak. Even the most optimistic believe we’re in for a couple years of rough times financially. The pessimistic are whispering we could be heading for an economic collapse to rival the Great Depression. In either case, prudence would indicate that it’s time to buckle down.

For myself, I will continue following the tenets of the “get rich slowly” philosophy. I’m going to stick to the basics. I’ve shed my non-mortgage debt, and I don’t intend to take on any more. I will continue to save. I’ll stick with the frugality that has served me well over the past three years. I will live below my means. If my friends ask my advice, I’ll recommend that they do the same.

Now is not the time for $2,500 plasma televisions. Nor is it yet time to store bread in the closet. But it is time to stop spending and to begin saving. Just like our grandparents did.

Note: Please see the comments for some important clarifications of these economic notions. For example, real-life economist JerichoHill writes: “The Personal Saving Rate is a very poor metric. Most folks save via IRA and 401K. So we should look at that savings rate, which is the National Saving Rate. The NSR shows the same disturbing downward trend, but is the more proper metric to use, in my opinion.”

This doesn’t change my primary point — that a return to frugality and thrift is the best way to cope with financial hard times.

The scary thing is at some point we’re going to have to stop the savings loss our else everyone will go bankrupt.

But at that point the huge decrease in spending will start quite the nasty recession, which in turn will promote further saving, etc. It’s hard not to believe we’re headed for the 1970’s all over again.

It’s funny how things are different in the UK. There’s currently a housing slowdown and credit is a little harder to come by, but it doesn’t feel anything like a recession. Maybe we aren’t going to have one, or it’s just the lull before the storm, but it’s certainly different.

The US are in for some troubles time. The good point is that the rest of the world now seem to be able to resist a weak US economy. The snow-ball effect should be less dramatic than before (1970’s)…

Yet, to come back to the article’s points, shouldn’t we at all time stick to the “get rich slowly” philosophy? The best times to prepare for tough times is when all is going well. The best way to get through tough time is to stick to the good old personal finance basics of spending less than what you earn – or doing your best to achieve it!

So far , in canada, housing prices are still increasing as the market continues to do very well.

However, it isn’t rocket science. Eventually debt does get outof control, and the cumulative effect of so many people living beyond their means can only result in an economic slowdown when we all start , like me HAVING to live cash only, and then only on a limited basis with so much money going into paying down credit cards, instead of into the legitimate economy.

Our banking and lending laws are , and have always been much stricter than in the US, which is one reason why it is not nearly as bad up here in the Great White North. For example, one crdit card cannot raise your rates arbitrarily because of your history with another company, and when they do, they can only go so far.

What a timely article! Considering the Visa IPO was just a few days ago that turned out to be the biggest in US history.

Anyway, I find it particularly disturbing when we’re in an age that consumerism is the ideology behind of our times, being pushed by multinational conglomerates to fatten their bottom line and in turn diverting our precious dollars that should be put towards savings.

Thank you for writing this article 🙂

– Will

I do not think frugality is lost, but people have not been forced to practice it as a defensive measure. I like being frugal and I save my money each paycheck. However, if the news is truly as bleak as everyone says it is, even I will have to tighten my belt and find new levels of thrift. Being in my mid30s, I have either been too young or too unaware of recessionary periods to feel the pinch.

I agree that credit cards (and the easy ability to spend money) makes one feel richer. I hope the doom and gloom crowd is wrong but I also hope that people wake up and save more money for the future. Saving for that $2,500 plasma TV rather than charging it is more worthwhile goal.

Credit cards prey on people. There’s no other way to describe it. I get at least two credit card offers through the mail every day. They offer freedom, points, rebates, savings… anything to get me to sign up for that card. They promise me it will solve all my problems, save my financial life.

Luckily, I have learned through past mistakes and know better, but how many unsuspecting people haven’t?

These crazy offers should be against the law.

Lisa

The expectation of the “gotta have it now” attitude is certainly driving the savings rates into negative territory.

Some parents may be upset with their childrens lack of fugality, but there are other parents who encourage their children to purchase extravigant things because they want them to have a better life than they did.

I think it’s a cycle of being too busy, therefore feeling stressed, then seeing “everyone” (read: someone on TV, one conspicuous-consuming friend) having “more,” then feeling deprived, then longing for comfort, then trying to fill that need with MORE: clothes, eating out, better car, vacation, whatever.

Usually, you *can* find that “ahhh…” feeling of relaxation with a cup of tea, a hot bath, a great home-cooked meal or a good laugh with a friend. But it’s easy to think spending more will make it better, faster, or that you “deserve” something that only can be bought. And yes, there’s a spirit in this country that it’s uncool not to resolve these issues by spending.

The sensation of entitlement is a terrible way we cause ourselves pain — and justify spending all our money and more.

First of all, she should stick to speaking for herself. I know how to be frugal and save my money, thank you very much.

Second of all, economic indicators show more than that people are bad savers, though I agree that too many don’t save. Real incomes have dropped, costs of housing, education and health care has skyrocketed. It isn’t as easy to make it today. The postwar US economy was a different world.

I don’t know if it’s adressed in that book, but didn’t all those crazy 1920s spenders turn into our penny pintching “children of the Depression” grandparents? There is hope for us yet.

And keep your bread ends in a bag in the FREEZER. After you’ve built up a bit, spin them through the food processor for excellent bread crumbs.

I agree with this article also. We need to heed the warning signs and cut back as much debt as we can now. I am blessed that I also don’t have any non-mortgage debt and I plan on keeping it that way!

I think that we got ourselves into this very trap. As my salary increased, so did our “needs” which led us into the mess we’re in now.

I’m thankful that I found things like Dave Ramsey’s book, and GRS before it became too late for us. We’re on the road to recovery and much happier because of it.

We’re doing our best to push that “personal savings rate” line up!

Thanks for all our work J.D.!

I’ve only recently become aware of how I spend my money (2 years) and I regret a lot of foolish choices I’ve made.

As I’m becoming more frugal, I find myself thinking more and more like my grandmother, who found ways to use many things. She was also great at savings as she had years to develop the habit of waiting until you had the cash to buy items.

My grandmother used to drive me absolutely crazy with her frugality. For example, whenever I threw post-expiry-date food in the garbage, she would fish it out again and say “you can still eat this, it’s okay!” Yuck! And she would recycle my long-sleeved blouses for me by simply cutting the sleeves off and stitching them up by hand to make them into summer shirts. In recent times, I’ve really come to admire her frugal practices, and I even wished I’d gotten into the whole frugal thing before, when it could’ve made a substantial difference to my life.

In the last few months the local news has interviewed middle class families in my area on how they are handling the incipient recession. I always have to laugh at these “Cutting Back” segments. I’m not exaggerating, “cutting back” for these people means buying fewer drinks at Star Bucks and keeping their 5 year old car another year.

Ya baby, TIGHTEN that belt LOL.

In the end, someone always has to pay.

Bad attitudes about credit are self correcting. People with faulty views about credit, sooner or later, will not have money. Then they will learn to adjust. They will have to.

The trick is to not have the consequences of such bad habits cascade out into the lives of other people — as we are seeing with the legacy of the junk mortgage loans in the US

And the saddest thing of all is that our govt is setting the example by being trillions of dollars in debt. I still have friends who spend like there is no tomorrow…makes me wonder too where will it end? Could our govt go totally bankrupt too?

The idea for this generation would be to spend right rather than be thrifty and get value for your money.

The Personal Savings rate is a useful but somewhat misleading report (as is anything coming from the Federal Government). The report does not include Capital Gains, or any investment gains from IRA’s, 401(k)’s, or increases in Pensions. The Personal Savings rate is essentially money earned that is not spent.

Prudent investors and those who are careful with personal finance should “spend less than they make” but should also tend to the primary goal of increasing net worth…

This is a trend thats existed for centuries. There is evidence the ancient Egyptians (no I cannot cite) had credit systems.

Any economist will agree the on benefits of credit and how it can stimulate economic growth. Just every 30-50 years, we get ahead of ourselves. We overinflate and then deflate over a few years – recession.

Most people that read personal finance blogs won’t suffer much because of it, we mostly know how to use credit. The one’s that don’t, become the next generation’s thriftiest group due to their suffering.

Its tragic, but nothing new. And I would contend that now is the time to buy what you have been wanting, IF you have the cash. I got my car for 20% below sticker because sales are so slow. This was a car released just last fall and is in fairly high demand, relativley.

@financial philosopher.

Nail on the head my friend

To bring this matter home: Recently a friend of mine had to borrow a large sum of money from me because he has no savings and something came up. I am talking many thousands, and this person makes three times my salary (read: hundreds of thousands) per year. He also *spends* hundreds of thousands per year and has ZERO savings. What is wrong with this picture? And how do I talk to him about it before it’s too late?

JD,

This point does need to be addressed. As TFP pointed out above, the Personal Savings Rate is a very poor metric. Most folks save via IRA and 401K. So we should look at that savings rate, which is the National Savings Rate, which has been steadily declining for two decades but is not yet negative

Secondly, the “wealth effect” is a bit of a misnomer. What that effect is would be the nominal increase in spending, but not the percentage increase. As one gets wealthier, their marginal propensity to save rises, because they’ve already taken care of necessary consumption. What one sees in consumption is a switch to better, or more luxury, items.

Thirdly, the GRS philosophy to me is an everyday philosophy, in good times and in bad.

Great comments so far, everybody. A couple of things:

Rebecca wrote: Didn’t all those crazy 1920s spenders turn into our penny pintching “children of the Depression” grandparents? There is hope for us yet.

Ah — excellent point! 🙂

@Financial Philosopher & JerichoHill

Thanks for the clarifications. I’ll post a disclaimer at the head of the entry.

There is one major piece of the why people save or not missing here, and that’s the interest rate. Notice how the chart peaks in the early 80’s when interest rates peaked and how the savings rate bottomed out a little after 2000, when interest rates were at historic lows.

Although we are irrational sometimes, as a whole we make rational decisions, borrowing money when interest rates are low and saving money when interest rates are high.

I’ve done consider research on this topic and have several other thoughts, maybe a bit more from the “dark” side, I might share beyond what made it into the article.

Our entire credit system is totally out of whack. Whether it is weak mortgages (e.g., mortgages without “real” estate value to back them up, mortages without the income to support the long term payments), credit cards for anyone and everyone, credit card fees and practices that used to land folks in jail not so long ago, and retailers who design sale systems that require the use of “their” credit card in order to get the discounts (I coudl go on and on), the credit system entices or drags consumers into the web and eats them alive if they are not extremely aware, cautious, and frugal. There is nothing inherently wrong with credit, I’m not sure how we could survive without it. But the lack of responsible government regulation allows greed to grossly interfere and ruin the lives of many consumers–and I am usually against government intervention.

If that was not enough, government spokespeople get up at the podium and beg consumers to go out and spend their money, not save it. It is almost unpatriotic to not spend more than you make. Hey, you want to be responsible for ruining the economy? No one said, “Once you get your incentive rebate, put it away so have a little cushion to help you when this recession really takes hold,” did they? At least if they did, I never heard it.

And consumers also need to learn how to be more cautious in their spending. This site covers this topic quite well, so I’ll save those comments for another time.

Thankfully, I hit my low point in college and it was only a few grand. I haven’t charged a dime on a credit card in nearly two years and have paid down much of my debt. I’m not saving as much as I’d like to, but once the debt is paid down, I’m set to start building wealth and not debt.

Not only do people under 40 save less, but they have less to save.“

D’OH!

If you have less to save, it’s no surprise that you save less. I’ve been saying as much for years.

D’OH!

I just read an excellent essay this week by Matthew Crawford that speaks, in part, about the role industrialization played in the creation of consumer debt. (Crawford specifically links Ford to this phenomenon.) His thesis: People will stay in boring, dead-end jobs if they think it will help them pay for their wants over their needs. In other words, if you’re deep in debt, you won’t quit your lousy job. The minute you have debt under control, or eliminate it entirely, you’re more likely to quit/retire/become self-employed and seek more meaningful work. Hey–no wonder I haven’t had a real job in 12 years!

I found his essay here:

http://www.thenewatlantis.com/archive/13/crawford.htm

Thanks for a great piece.

Given government policy, there has been little point to saving, at least in U.S. dollars.

I saved several hundred thousand dollars (CDs, money markets) over the last decade to pay for my mom’s nursing home bills in case her money ran out (she finally died end of last year)

In that timeframe the value of the U.S. dollar has dropped by at least 1/3, measured either in domestic purchasing power or against international indices.

Sorry, but most days I feel like the world’s biggest chump – should have bought that McMansion like my peers.

We’ve had huge asset bubbles recently – stock market to real estate now to commodities – but even the commodity market’s looking shaky with the upcoming recession.

I think it’s going to be as bad as 1981, which I would argue was our most recent, significant recession.

I’m only 34 and I can remember a time when credit cards were taboo. My parents didn’t have one – too poor – dad was a teacher and mom a teacher’s aide – their income wasn’t high enough to “earn” a credit card. I can also remember my father trying like hell to get a home loan – excellent record of rent payment, good credit and all – but he had little collateral and didn’t seem to be a good risk for the banks. I contrast that with my own experience in 2000 – my husband and I had no problem getting a home loan for 6X’s what our income was at the time – and we had the opportunity to get credit cards galore!

Another incident I remember well is looking for something in my grandmother’s house about 10 years ago. We would often use her small 2 bedroom house as extra storage for all the crap we bought. My grandmother is not a poor woman – she’s quite comfortable, but I remember going through the house and closets thinking “Where is all her stuff?” I even asked my dad about this “Where’s the stuff she owns?” Dad just explained that she’s a child of the Great Depression and doesn’t buy “stuff” – she has a modest house, car, tv, a few books, and a loving family – that’s all she needs. How true!

In many ways I do live like my Depression-era g-mother. I have a modest (easily afforded) house and an older, reliable (paid for) car. I know I spend more on convienances like pre-cooked foods and eating out, but for the most part I’m far more frugal than most folks I know.

All disclaimers aside for other savings options, I think it is safe to say that Americans on the whole are saving less even when many are making more. We have much higher expectations of what we should be able to own. Amen to the continued call to action to conserve more and spend less.

I’ve begun adopting some of the practices of my depression era grandmother to save costs. While I don’t store bread in the closet, I buy whole chickens and cut it up myself, buy from the bargain bin, sold old things I don’t need anymore, etc etc.

I’m so glad that I paid off my debts right before this really went into the sinkhole. I don’t have a ton in savings, but I’m infinitely better off with little savings and no debt. I’m going to keep my depression era grandmother in mind when we get out of this and not owe anything to the banks ever again.

They have a lesson in frugality they need to learn – maybe they shouldn’t have been paying out $35 million dollar bonuses when they should have been saving and investing it?

It’s important to note that the “negative savings rate” is a bit of misnomer. It only includes savings of TAKEHOME pay, i.e. it completely ignores 401k savings and most investment income. That is, a person could be saving 20% of their income in their 401k but still have an official savings rate of 0%. It’s pretty misleading. Increases and decreases in wealth are far more instructive.

One thing that sticks out to me is student loan debt is the kickstart to a lot of middle class debt today.

First, it’s a necessity for many. And by the time you graduate, into an entry level job making peanuts, you’re already $20,000+ in the hole. At that point, what’s another $2500 on a credit card for that TV that you’ll get to enjoy?

Now fast forward 7 years. That 22 year old has married someone of similar class, who probably has about the same student loan buildup. Instead of the TV, she’s bought a car she can’t really afford. And they really want a house so they can start a family. So they take the ARM mortgage, thinking “in 3 years we’ll have better jobs and can refinance”. The baby comes, the diapers or dinner out go on a credit card since things are a bit tight.

Then the ARM adjust hits, and that payment they could barely afford is now double. AND they’re still trying to pay off that TV on that credit card from 5 years earlier which now has $40 worth of diapers and dinners a month added to it, the car that was out of their price range and needs new tires now, and trying to pay that student loan debt, that is 1/5 of their house value.

I’m 30, and just described 1/2 the people in my age bracket.

@Muck:

I agree in some respects that I don’t want to lose my primary job because of my debt load (not that I mind my job that much) but also looking at our debt load vs. our coming expenses gave me incentive to do more.

Perhaps unexpectedly my hatred for our debt has caused me to begin to learn all those things I never cared about before: how to invest, how to take care of money, how to start businesses, etc.

I’m certainly no expert (yet), but when I saw the size of our debt, it finally woke me up to the reality that I was not being a good father nor a good citizen by living my consumerist lifestyle.

Once I get my debt under control, you’re right that I’ll feel much more free to take more risk. Heck, even paying off the little debts have helped with that.

Why does it have to be save or spend? Its all about balance yo! If everyone started saving like mad, we probably would see a depression of sorts. The system depends on you spending your money. I like the system so I will continue to pump what I can into it. I also like having money in the bank so I will continue to save. Balance!

Personal Savings Rate is a FARCE!!!

It is at best a poor metric for measuring what someone is saving. It doesnt include retirement savings or home values. Sure home values in some areas might be going down the past year, but look at the value compared to 5 years ago. Example, the past 5 years i have maxed out my 401k and my IRA. They have returned on average 8% each year. I also purchased a 200k home that is now worth 300k. My retirement accounts are now worth 160k. So in the last 5 years my wealth has increased by 260k. however my “personal savings rate” is zero. Now tell me how that is a good metric.

Rebecca, the spenders helped to cause the Great Depression. We hope our contemporaries will turn frugal, but it might not happen until many people become much poorer.

I don’t save bread crusts. If I have bread, I eat the whole thing, crust and all. I do frequently shop clearance racks and discount bins though. I pay full price for very few consumer goods nowadays.

I remember as a child watching my grandparents look on with barely disguised contempt as my parents ‘purchased’ (meaning, financed) a BMW, but had no savings to speak of. Grandma and Grandpa weren’t wealthy by any means, but they owned their home outright by the time they retired. They were able to purchase a fifth-wheel and travel the U.S., Canada and Mexico. My grandmother, who is still alive, is able to pay $3,000 a month (or more, now) to rent an apartment in an ‘independent living’ residence.

The thing that sticks out most to me is that when my grandmother sold her house and moved, she had to downsize. My mom told me that grandma still had (AND USED) a toaster that was about 20 years old. Same thing with her iron. How many of us can say the same????

I believe this is my first time commenting on your blog. I have been an avid reader for about 9 months. I would like to congratulate you on your new found “freedom” and self employment.

My husband and I have used several ideas from your blog and I am proud to say we will be out of non mortgage debt in July. We do have school loans (good debt ratio for the education if you ask me) for one of of us, but I am so excited for the end July to start saving!

Thank you for your dedication and daily doses. It has helped my family tremendously and it has changed my daily habits and outlook.

I think that a large part of what we’ve seen in the last decade–credit card offers coming out your ears, ridiculous mortgages, etc. etc.–is a result of capitalism trying to come to terms with new information technology.

In the 70s, there were credit cards, but how they were able to be used was much, much different. I remember my mom using a store card at Montgomery Ward; the cashier had to pull out a book the size of a phone book and look up her account number to make sure it was still an active account. Inactive accounts were crossed out with a pen, if I remember correctly–book by book across the entire department store chain.

I also remember cashiers making phone calls to some central information source to affirm that a credit card number was legit and/or hadn’t gone over the limit. Remember that this was in the day that credit card numbers were recorded by putting the card in a holder and running a carbon copy. Accounts were tallied manually, or at least certainly NOT electronically like they are today.

God, I feel like a geezer writing this. (“Why, when I was a little girl we walked uphill both ways in the snow!!”) But the point is–the Internet revolution in the 90s is what made it possible for all that information to be handled instantaneously, for credit information to be aggregated, for credit *scores* to be formulated and statistically validated.

Being a lender has always been profitable, but the technology boom opened up more possibilities for exploiting that than ever before.

The profit motive and good ol’ capitalism inspired companies to push those new capabilities as far as possible (and we hardly have to mention the brand-new, wide-open possibilities for fraud–I’m talking to you, Casey Serin). Now the system is getting a real good sense of where the sensible limits actually are. My guess is that the system re-equilibrates, credit scores and other methods for evaluating risk will still be used, but there’ll be new regulations or at least “best practices” that make the economy sustainable with these new technologies.

Til then–I’m with JD. Pay off your debt, feather your nest egg, get grounded. I recently read The Worst Hard Time, about people who lived in the Dust Bowl during the ’30s. Definitely puts the current situation in perspective! Highly recommended.

I agree that the personal savings rate is a meaningless metric. Because it only measures earned income, this means that retired persons living off of their investments have a strongly negative savings rate, which will naturally skew the results.

I’m just a few years older than the author of the Newsweek column, but I have 2 kids and a SAHP spouse whose 10 years older than the author. Even at 36, the author only responsible for herself and not thinking about leaving paid employment, yet. The phrase “late-onset adulthood” comes to mind.

I guess it isn’t that surprising that we’re more conservative with our finances than she is. Well, more conservative in terms of debt, savings, and monthly cashflow levels. On the other hand, I think we’re actually more radical about the lives we want to have, because we’re thinking further ahead, and being at the mercy of a boss to get by every month isn’t a big part of our future plans.

Its interesting that the peak of the savings graph also corresponds to the switchover from conscription based warfare to an all volunteer army in the mid ’70’s. My generation is the first to not have to actually make any sacrifices for our freedom.

This would manifest as an inherent general feeling of stability and security derived from not having the possibility constantly looming overhead of having to go fight a war. The world would seem like a much safer place, you would consume more and save less and also care less about the bad stuff going on in the world.

Just a theory.

Regarding the personal savings metric, the validity or value of the metric means very little, in reality. The fact is well known that Americans are not saving like they used to, and are spending more than they make. That’s why the credit industry is losing billions on loans to people who weren’t able to repay.

@Finally Frugal: “a toaster that was about 20 years old. Same thing with her iron. How many of us can say the same????”

Yeah good luck finding products on the market these days that will last that long. It seems the consumer grade products these days are designed to last a few years, wear out or break, and then we have to buy the latest and greatest (and higher cost!) model.

“People in their 30s haven’t really experienced a significant or long recessionary period,” says consumer behaviorist Larry Compeau of Clarkson University.

So I thought the 70’s were a recessionary period (1973?)? It sure did seem like it to me. I remember my mom hopping from job to job and never having enough money for anything. I realized pretty early that I didn’t want to have to live that way if I could help it. This is why I save so much now and have no debt.

I wrote a follow-up to this post which explains why the personal saving rate might be considered a poor metric. I’m not sure if I’ll post it. I don’t feel it’s wholly necessary — you folks have done a good job of presenting its downsides.

In my research, I found an interesting discussion of its validity from a couple years ago. I’m not sure what I think.

Regardless, a couple of people have noted that this piece is a little “dark” for GRS, and I’m inclined to agree. I don’t mean to be the bringer of storm clouds. That’s not my role. My aim is to help people keep a warm fire inside even if the weather outside is nasty. (Hm…that’s really stretching the metaphor.) I’ll try to steer clear of this sort of stuff in the future!

I like to call this the “Apple lifestyle”. When simply having the latest useless gadget outweighs saving for the future.

Um. Wage growth has been positive only when discounting inflation. Taken with inflation wage growth for non-management positions has been stagnant or even decreasing in recent years.

Of the three possible causes listed by the Federal Reserve Board of San Francisco, I feel that easy access to credit is the most likely cause of the decrease in savings. People in our generation rely more and more on credit cards to cover emergency expenses.

Finally Frugal asks: “My mom told me that grandma still had (AND USED) a toaster that was about 20 years old. Same thing with her iron. How many of us can say the same????” I just wondered how many of us think the toaster we do have will last 20 years? Few products seem to consider durability to be worthwhile any more. This idea has come up before. It might just be cheaper to buy that $100 toaster that will last 20 years, as oppossed to buying a new $20 toaster every 2 or 3 years.

J.D.,

I would like to encourage you to continue to write some of these types of stories. Even if you felt that the story was “Dark” (and by the way, I did not feel that way about it), it is relevant to the atmosphere that we are in today. Recession or not, I think a lot of people are starting to take a good hard look at finances, and articles like these bring a different perspective to the table.

Keep up the good work.

Ian

just

“It might just be cheaper to buy that $100 toaster that will last 20 years, as oppossed to buying a new $20 toaster every 2 or 3 years.”

That is, if the $100 toaster (or whatever appliance) is better made than the $20 one, which isn’t always the case. Take the example of a toaster oven…my husband recently researched them online, and the expensive ones were just as crappy as the cheap ones. They just had better looking exteriors with stainless steel or other trendy extras that increased the price. But they had just as many negative reviews from purchasers claiming that they broke within a year or two. We ended up buying the low end one, since there seemed to be no discernible quality difference.

I’m not arguing that quality differences don’t exist among products, but you can’t assume that a higher price equals better quality. You must do your research so that you are not bamboozled by sleek design.

My gut sense is that no toaster made today will last 20 years.

As a point, I think its okay to consider one’s home part of the wealth equation if you account for that its value in average is probably 10% more than its actual market-clearing value, and 20% more in current bubble areas.

Talking and preparing for bad times by practicing good fiscal policy, keeping good health, and always trying to improve one’s position is a topic of merit during any economic time, good or bad. It is in the excess that it becomes worrisome.

I think some famous Greek said that virtue lies in moderation.

Sorry, didn’t mean to start The Great Toaster Debate! Actually, I agree that items these days aren’t made to the same exacting standards as they were 20, 30, 40 years ago. But also, having just read SkyMall mag on a recent airplane trip, there are just so many other fancy gadgets out there to lure us into thinking our ‘old’ toaster/telephone/TV/(insert item here) needs to go.

p.s. my toaster was free. It really sucks at toasting bread consistently, but I’ve kept it, because, hey, it was FREE.

Funding your IRA or 401(k) should not be counted in the savings rate because that money is designated for a specific purpose – retirement – and it’s not easily accessible in the event of a financial emergency.

escapee:

This person makes 3 times as much money as you. You lent them thousands of dollars being fully aware of how horrible they are with their money. I sure hope you wrote out a contract with them stating that they’d pay you $x/month or so.

I’ve learned the hard way. Lent money to family members who were horrible with money. Took them inheriting money over 5 YEARS later to finally pay me back. And they only paid me back after me nagging them constantly, and they had the nerve to get angry with me saying that me nagging them is annoying.

I couldn’t believe it. I was stunned for many days. I felt sorry for them, tried to help them out and this is how I get repaid? Finally they paid me off a few weeks later and I vowed never to lend money again to anyone like that ever again, family or not.

Wouldn’t the continually decreasing interest rate have to do with the decrease in savings.

I remember hearing that in the late 70s and early 80s that you could find savings accounts with 18% interest. I’d save a lot more if I got that return rate.

Every time I read this type of story, I’m grateful for the decision my wife and I made when we first got married. We currently save 17% of my salary. We only have mortgage and student loans. While we’re upgrading our home, and will be incurring a big jump in monthly expenses, we’re doing so at a time where we won’t have to change our savings rate and home prices are low*.

*relatively speaking.

For what it’s worth, JD, I don’t think this is gloomy. Far less gloomy than the financial news on the business page of the newspaper these days, that’s for sure!

On the subject of the 20 year toaster, I think it’s still quite doable (and even common) to get/have/keep household goods for that long. In our house we’ve got some kitchen goods (including our toaster, stand mixer, microwave, dishes and silverware) that will hit the 10-year mark this year–got them in the year we married and bought our first house–and they’re still going strong. We have quite a bit of stuff that predates these items, too: bookshelves, major furniture (bed, dining table and chairs, lamps).

We’ve replaced the mattresses and lampshades a time or two, though!

My husband got our TV when he was in college 20 years ago–it’s soon to be technologically obsolete, so I guess we’ll need to replace it. But it’s still working just fine for our needs. I’ve had my sewing machine for that long, too, and it’s still chugging along great (and I got it used–it’s a mid-60s, toothpaste-blue, all-metal Singer. I doubt it’ll ever die!)

I don’t think we’re alone, not by a long shot. The households of our good friends, the ones we’ve known long enough and well enough to have a sense of their household inventory, are along the same lines.

Maybe it’s freaky to think about having posessions for decades when you’re in your 20s yourownself. Get a little further along and you may be surprised how long some of your stuff has been with you.

(Dang, I’m feeling old on GRS today!)

two things: 1) I’m with the folks who say this isn’t a too-grim-for-GRS topic. If things continue as they have been in the US economy, there will be plenty more of these kind of topics to be discussed!

2) I wonder if “savings” should also include the intangible–stuff like social capital. During the depression, people didn’t just help their own families, there were many examples of people who developed community efforts to help their community members survive. Over the last 10 years I’ve three times given good friends a month’s rent when they were suddenly faced with an unexpected economic situation (divorce, unemployent, and an educational timetable that collapsed). I didn’t ask or expect to get the money back; these were not exactly gifts, they were “I see what I can do to help you” efforts. I’ve never had to ask in turn, but I do feel that these folks (or others with whom I feel equally close) are as much a part of my emergency fund as the actual funds I have.

I hope to never have to call on my social/friend/family network, but I wouldn’t be foolishly too proud to admit it if I needed help.

64 comments, and I’m surprised that no one has pointed out the most glaringly obvious problem with the “negative savings” statistic:

EVERYONE in this country who CHOOSES to work hard and earn an honest living, a full-time job, is being strong-armed by the government into “SAVING”:

YOUR PART (up to ~$100K): 6.2%

YOUR EMPLOYER, instead of passing on to you: 6.2%

TOTAL MADNESS: 12.4%

So everyone of us who is working hard to earn a living is paying at least 12.4% of our income into a forced savings fund called social security.

Folks, this statistic is meaningless. It’s up to us to figure out how to spend the 87% we have left, save and give properly.

On the subject of old kitchen appliances, I have a hand mixer from the early to mid 70s that I inherited from my grandmother. Works ok, I think the motor is a little slow, but it’s only for making cakes and pancakes with anyway.

Go to youtube,search for “the story of stuff”

As intro to it says it will “The Story of Stuff http://www.storyofstuff.com will take you on a provocative tour of our consumer-driven culture ”

pretty good–

The best way to cope with financial hard times, was best said, I believe, by Mary Hunt’s website:

1. Live below your means. Do not buy stuff you cannot afford.

2. Control your spending. Stay away from malls, online shopping, catalogs or other places that allow you to overspend with ease.

3. Reduce your expenses. Everything from the water you use to the gasoline you burn. Start tracking your expenses, then employ every possible tactic imaginable to cut some from every area.

4. Pay off your credit cards every month. If you are carrying balances, get those cards out of your possession so that you are not tempted to use them. Once paid in full, carry only one card with you and clear it every month as if your life depended on it.

5. Save. Save. Save. You need a good, healthy cushion of cash set aside to carry you through the unknown that lies ahead.

6. Pay off your home mortgage as quickly as possible. Once your unsecured debts are paid, tackle the home mortgage with a vengeance. This is the only assurance you will ever have for a rent-free retirement.

If you do all 6 of these things, you will recession-proof your life. That means you will be so well prepared, so financially fortified, that you will be able to not only survive, but also thrive during any coming recession.

Toasters. Argh. All I want is a toaster that actually makes TOAST, not warm bread. If it would last a few years, that would be good, too. Talk about sounding like a geezer, Angie: I can remember when toasters did make toast. Poor old bat.

The problem with the theory that a better savings rate and a national frugality binge will help the economy is this: the United States no longer manufactures anything of substance. What we “manufacture” is frantic, circular activity.

Our economy is no longer geared to manufacture and trade things of value and use. We spend our money on things that come in from overseas, but we don’t earn our money by manufacturing things to sell–most of us earn our money by serving other people in one way or another. It’s circular: an economy based on service produces nothing except a need for more service. It’s like cleaning house: the more you clean it, the more you have to clean it. And we also manufacture debt, the engine of our financial industry. When people stop buying junk and quit paying people to do things that they could do themselves (such as cooking and serving their meals), the economy is gunna grind to a halt.

When was the last time you bought a product that actually was made in America? Even items whose advertising imply “made in the USA” are largely manufactured offshore.

So you say all those swarms of new houses are products, right? Even the housing industry is circular: people no longer buy houses to live in for the rest of their lives. They buy a house so in three years or seven years they can buy a bigger house. It’s not a real product; it’s more like a service. A realtor once told me that after ten years a new house is considered “Old.” That’s outrageous! He admitted that in effect the new construction of the past twenty years or so is throw-away junk.

I’m afraid The Shrub is right, though probably not for reasons he understands: the economy has evolved to the point where if many of its citizens quit spending more than they earn, it will collapse.

I’ll weigh in on the ancient appliance issue. I am a serous case of “don’t replace what works”. My dryer is 23 years old, as is my refrigerator, my washer is 30+, my ancient pop-up toaster is 50+ (grandmother to mother to me). I could go on, but I think I’ve hammered on the point well enough. All these things still function, I see no reason to replace them.

I’ve always had some degree of frugality in my makeup, it just got a boost when I discovered GRS and some of the other sites linked from here. I still did expensively stupid stuff early in life, but I know people who may not live long enough to get out of debt. I expect to be clear of everything but the car note by year end if nothing else expensive happens. Of course, such stuff does happen now and then, as my original goal was aimed at four years ago. Oh, well.

If I include my employer’s match, I’m putting 29% (23% w/o the match) of my gross income toward retirement in a 401k and Roth IRA.

Seems as if some part of that should be considered “savings” especially since with the Roth, principal can be removed without penalty.

There is some incredible data and information in this post. I’m still trying to catch up when it comes to saving after years of not taking it serious enough. Obviously hindsight is 20-20 for me now, but I’m really kicking myself. This article just makes it that more evident the need to spend less and save more in general. Thanks JD.

J.D.,

This is my first time posting. I’ve been reading your site for months now, and it’s taught me a lot. I’d like to de-lurk a minute to encourage you not to shy away from “dark topics.” By bringing unpleasant subjects into the light, it raises more awareness, and I think it’s a good thing with this current economy. Thanks so much for your hard work.

JD — given that we’re probably in a recession, why is it “dark” to talk about it and how it could affect our lives? I lived in California a long time, so I’m used to the “must pretend to be happy happy” thing; I didn’t know that Oregon was afflicted with it, too. 😉

I agree- we need to face reality here and prepare for it accordingly. Sometimes the truth is “dark”, but burying our heads in the sand about it isn’t going to make it go away…

a good article in today’s NYT about this:

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/21/business/21econ.html

David (Comment #64):

I’d agree with you if any of that money was actually going into any sort of “savings” account. Instead, the government is simply spending Social Security money just like it spends every other dollar it brings in; our current Social Security dollars go to pay back the people who were forced to “save” their money years ago.

As I recall, there was an attempt to convert Social Security into actual forced savings accounts, and people protested the “privatization” of Social Security. Not because it’s a bad idea, but because our current two-party system has become so polarized that nothing useful can ever get passed by politicians on either side of the fence.

I wish it wasn’t so easy for people to skew numbers. I read way too many people bashing my generation (I’m 24) because of our lack of savings. My husband & I save 10% of our gross pay into 401(k), 5% of our gross pay into our Roths, and 20% of our take home into a house savings account. In 18 months, we’ve managed to save about 1/2 of what we’ve made between everything. And we’re not the only ones who are doing so.

We’re DINKs. We can afford to save like that and still have our fun. No Wal-Mart runs or generic cheese in our house.

I think the government needs to find a new way to show the numbers, because these numbers (as everyone else has pointed out) aren’t showing the true reality.

I think it’s unfair to call consumerism and gadgetry the “Apple lifestyle.” One of the reasons I like Apple is that I have a 1998 beige desktop that still runs like a little tank… with OX X on it. Tiger, in fact. I haven’t upgraded anything to Leopard yet, or I’d probably try it.

Apple stuff is very pretty and moreish, but a lot of it is very well-made rather than disposable.

I think there is more to the problem than credit and credit cards (though I loathe how these practically serve as a new form of slavery for millions these days). If you look closely at the advertising/marketing done in the US, people are basically being conditioned to be good “consumers”. They are being quite literally brainwashed to believe that it is their right to buy whatever they want the instant the advertisers create the desire.

But more than that, people are being conditioned to constantly keep spending. They are told how important it is for the economy (and by extension them personally) that we all continue to spend, even beyond our means, to create jobs and stimulate growth that never really seems to trickle back to us. One ad I have heard on the radio has a fictional family talking (in a very obviously fake manner) about the virtues of some homebuilder’s “great deals”. The obviously fake little girl chimes in, spouting off some of the builder’s ad slogans and the father praises her by saying that she is “going to grow up to be a great shopper, just like her mother”. I seriously feel like I need to keep a barf bag in the car for the next time I hear that ad!

People are also being bombarded with the notion that they “need” credit cards to be happy and emotionally secure. An ad for a website selling secured credit cards asks the listener if he/she feels like a failure because they do not have a bank account or credit card. Since when did these become the measure of someone being a success in life? The ad very carefully does not explain out that everyone is automatically accepted for this miracle credit card (that they all but imply will do everything including improve your sex life) because you are basically giving them a chunk of cash, say $1000, then paying them an extremely high rate of interest (21% I believe) to use your own money!!! The advertiser even has the nerve to offer to “waive the fees” if you call “now” to in effect loan them your money at 0% interest and then pay for them to loan it right back!

Americans have become more productive and are, in general, earning higher wages

I’d like to see a cite for the claim that Americans are, in general, earning higher wages.

Savings need to start at an early age. Parents should encourage their children to save at a very early age and hopefully they will carry it into their earning years.

It’s amazing that kids out of college don’t take advantage of an employeers 401K right away. I guess they figure retirement is so far off that they would rather spend then save. What a mistake.

Seriously there is a serious problem with people saving money in this country. We can not get past the fact we need to have things that we don’t need.

It is just our culture that teaches us to live in the now. Not save in the now. Every time that we go out and spend money on something we don’t need it hurts us.