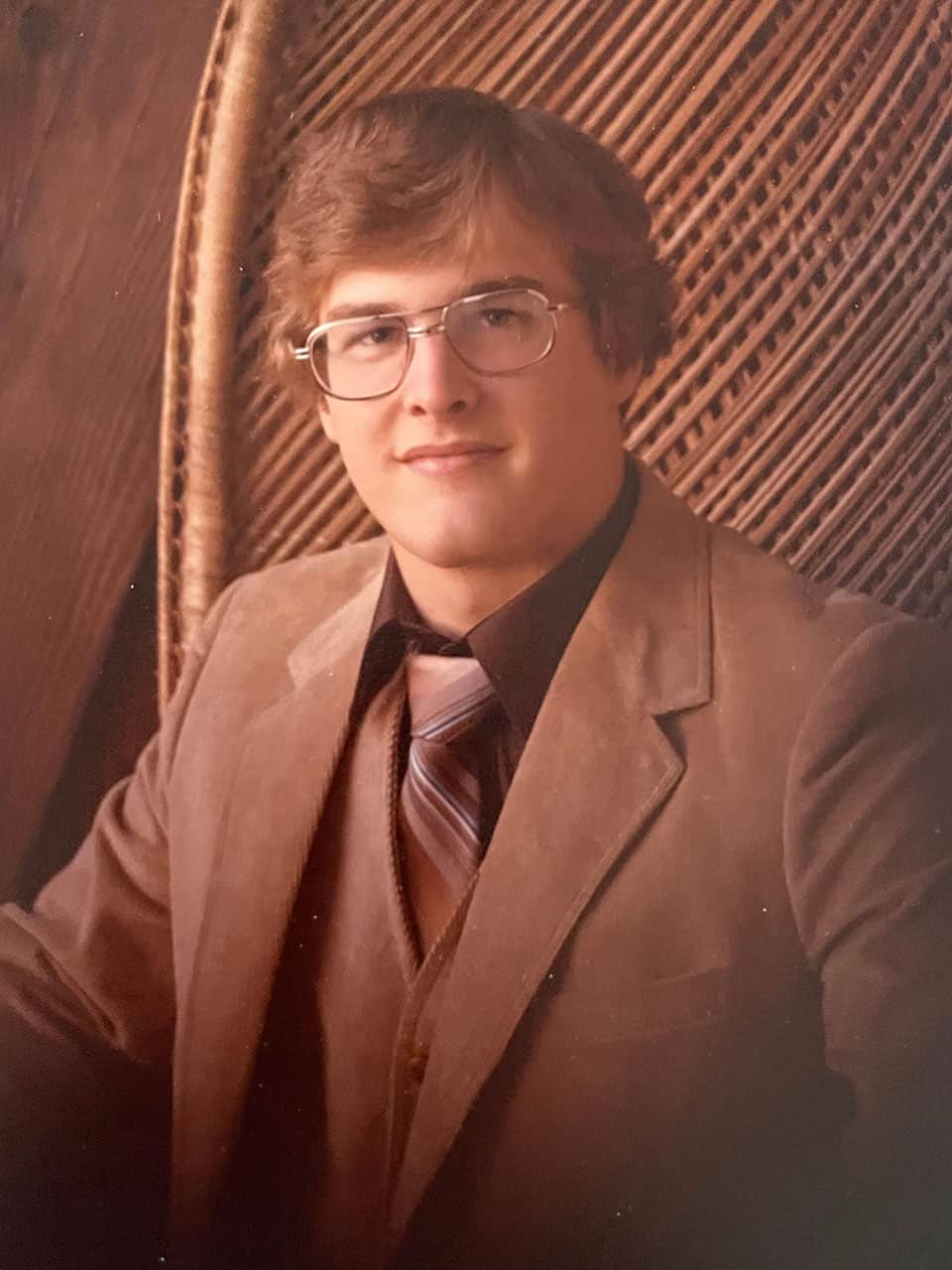

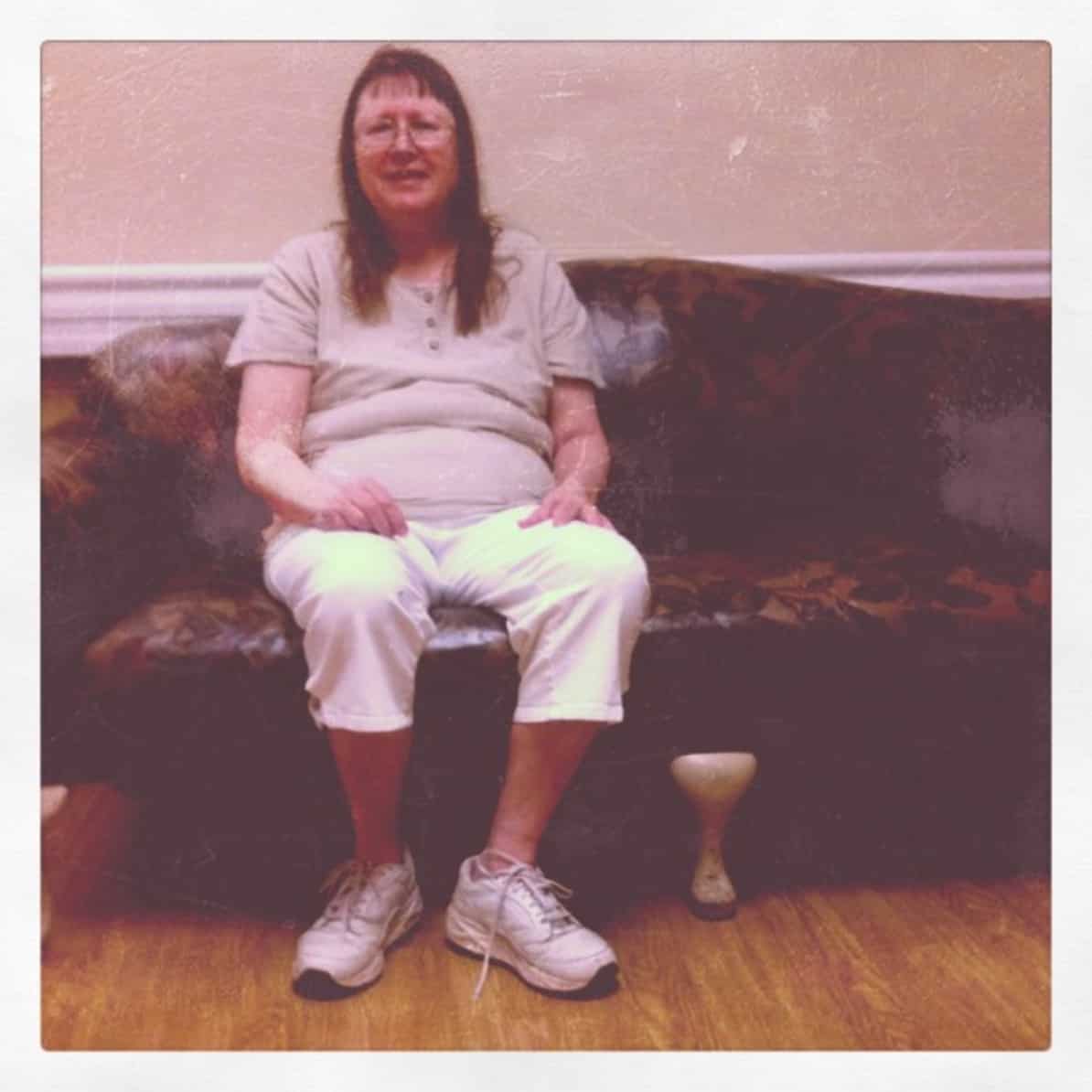

It’s December 1972. I am three years old. My parents have to be away for the night. They drive me to stay with Dad’s brother and his family. It’s cold and it’s raining. We stand on a covered porch and knock. A big lady with a big smile opens the door to greet us.

“This is your Aunt Janice,” Mom tells me. “And this is your cousin Nicky.”

You are standing behind your mother. You are eight years old. This is the first time we meet. You’re not interested in a little kid like me, and I’m too timid to pay much attention to you.

Mom and Dad leave. Your mother reads to me: The Little Engine that Could, Curious George, Doctor Seuss. You sit nearby and listen. Before bed, I learn that you wear plastic pants like I do. You’re a big boy but you still wet the bed.

It’s a Sunday in autumn 1978. You are fourteen; I am nine. My family is visiting yours after church. You are curled up in a chair watching football on a black-and-white television. You have a magazine in your lap. I am watching you watching football. We don’t have a TV, and I don’t know anything about football.

“What are you doing?” I ask.

“I’m watching the Pittsburgh Steelers,” you say. “They’re my favorite team.” You show me the magazine — an entire magazine only about football. It lists the teams and the players and the schedules for the entire season. You show me how you take notes in the magazine, writing down the scores of each game, writing notes about your favorite players.

I tell you that I like comic books. When the game is over, you take me upstairs to show me your comics. You don’t have many, and none of them are about superheroes, but when you offer me a Richie Rich, I take it home with me.

This is our first real interaction not as cousins, but as friends.

We see each other often at family gatherings during our childhoods. We are friendly, but the five years between us is a very real barrier at this point. Soon, that barrier will fall.

It’s sometime during 1983. I’m riding in the car with Dad. He hands me the newspaper and tells me to turn to a specific page. It’s an article about you. You are nineteen. You have been convicted of a crime, a crime that I don’t understand. Dad explains it. You’ve hurt somebody very badly.

We don’t see you at family gatherings for a couple of years.

It’s summer 1986. You’re living down the road at grandpa’s house. Since grandma died, he’s been struggling and it’s helpful to have somebody living with him. You have the entire upstairs to yourself. At first, I’m nervous about visiting you. You are a criminal. I cannot let that go from my mind. Eventually, however, I let my guard down. I allow myself to move on.

You’ve begun working for Dad as the box factory’s first employee. When I help in the shop after school, you and I chat. We talk about music. We talk about books. (After you read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, we talk a lot about Quality.) We talk about movies, especially your favorites like Being There and After Hours.

Now and then, I walk down the road to visit you. We sit upstairs and you play your records for me. You play Yes and Deep Purple and Queen. (You play me a lot of Queen.) You play Styx for me: The Grand Illusion. To you, it’s an okay album. To me, it’s a revelation. It becomes part of the soundtrack to my life.

It’s September 1991. I’ve graduated from college without a plan. I take a job selling insurance door to door. The job requires I live near Portland, so I move in with you. You’re renting a duplex in Canby.

Your home is a mess. It’s chaos. It’s a disaster area. There are dishes piled high in the sink. There are clothes piled high on the floor. There’s Stuff everywhere. But you have a spare bedroom for me, so I live there.

You work at the box factory. I sell insurance. In the evening, we chat and play games while watching MTV. Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is in heavy rotation. We don’t know what to think of it.

I buy a Super Nintendo. I buy a Game Boy. I buy a Geo Storm. “You’re spending a lot of money,” you tell me. “It’s money you don’t have yet.” You warn me about going into debt, but I don’t listen.

It’s spring 1993. You’ve been watching me struggle with money. You lend me a copy of The Only Investment Guide You’ll Ever Need by Andrew Tobias. You show me how to use Quicken to track my money. You teach me about mutual funds.

I begin investing $150 each month in Invesco mutual funds. You are pleased. So am I. But this adventure ends when I decide that I’d rather have a new computer. I cash out my shares to buy a new Macintosh. You are disappointed in me.

It’s autumn 1994. You’ve purchased a house in Molalla. But because you’re a cheap bastard, it’s a cheap house. It’s 80 years old. Maybe more. It’s in rough condition. You don’t care. It’s yours.

On Sunday mornings, I drive out to watch football with you. I buy donuts and chocolate milk, which we consume in great quantities. We watch the Pittsburgh Steelers. In the afternoons, we watch the Seattle Seahawks. Some days we play computer games instead. We play Warlords and Warlords II. We play Darklands. We play Civilization.

We have become close friends.

We attend concerts together. We eat dinner together. We talk about music and movies and games and books. You are one of the only people in my life who is willing to engage in deep, philosophical conversations and I appreciate that.

It’s July 1995. Dad is dying. The cancer is dragging him under. He’s decided to leave 60% of the box factory to Mom, 10% to me, 10% to Jeff, and 10% to Tony. He’s also leaving 10% to you, his nephew. More importantly, he’s leaving you in charge of the business.

Since your father died five years ago, my father has stepped into that role for you. He truly sees you as a son.

During the final weeks of Dad’s life, you begin leading the business. You’re also active in helping him put his personal affairs in order. The day he dies, you’re the one who is responsible for getting his will notarized. You personally dig Dad’s grave at the church cemetery. It’s a monumental task but you see it as a debt you owe him.

(Twenty-seven years later, I deliberately seek to pay you the same respect. During the last two months of your life, I’m with you as much as possible. “I want to be your hands and feet,” I tell you, and I mean it.)

It’s summer 1996. You have embraced your homosexuality. You are living the Gay Life. You are partying and dating and going to the gym. You introduce me to some of your friends: Tom, David, Shad, Hector.

You sell your house and rent an apartment in Portland. You begin to travel. You’re interested in European history, so you tour Greece and Italy with Hector. You make another trip to see Italy with your friend Kathy. You tell me that I ought to travel too. I’m not interested in travel.

You’ve been a life-long stamp collector, but now your focus turns to ancient coins. Ancient coins give you a chance to combine two passions: collecting and history.

It’s summer 1999. One afternoon I come back from making sales calls and have a bunch of trading cards in my hand. “What are those?” you ask.

“They’re Magic cards,” I say. I explain that Magic: The Gathering is a game played with collectible cards. Each card bends the rules in some tiny way. Your aim is to use your pool of cards to build a deck that can defeat the deck your opponent builds. “I guess it’s a little like the card game War,” I say.

I teach you to play. Within a few months, you know more about the game than I do. Much more. You become obsessed with it. You buy boxes of cards. You play in tournaments. You’re not especially good, but you enjoy it. And you have moments of brilliance. In fact, at one tournament you actually defeat the number one player in the world. Mostly, though, your play is fair to middling.

During the next 20+ years, you build a vast collection of Magic cards. You have thousands of cards. Tens of thousands of cards. Hundreds of thousands of cards.

You also dive deep into ancient coins. You order bags of “uncleaned coins” from internet dealers, then meticulously soak and scrub them. When they’re clean, you get the joy of trying to determine which coins you’ve acquired. You buy books on coins. You read about coins. You try to share your passion with your family and friends, but nobody else is interested.

It’s July 2007. I’ve just returned from my first trip to Europe: two weeks in the U.K. with my wife and her family. I’m back at the box factory but struggling. I don’t want to be there. I want to be anywhere but the box factory.

You are angry. You are bawling me out. “You never should have gone on that trip,” you spit. “Your absence made it abundantly clear just how little work you do around here.”

You’re not wrong. For a while, I’ve done almost nothing at the box factory. My attention has been focused on this blog, on Get Rich Slowly. In fact, I’m now earning as much from the blog as I am from the box factory.

“You’re right,” I say. “So why don’t I quit?” It takes a few months for me to get the guts, but I do it. I leave the box factory to become a full-time writer.

It’s November 2008. You and I spend an afternoon cleaning the moss from Mom’s roof. While doing so, we have another one of our deep conversations. This one is about money. It’s about wants and needs. I turn this conversation into a blog post, and the ideas we discuss become a key part of my financial philosophy.

It’s September 2012. You and I take a three-week tour of Turkey. We make it up as we go along. It’s the first time we’ve traveled together, and we’re pleased to discover that we’re perfect travel companions. There’s an easy flow to our journeys.

We enjoy strolling through Istanbul together, we enjoy taking the bus to Pamukkale, we enjoy the early morning hot-air balloon ride over Cappadocia. But we’re also willing to give each other space. I spend one day at the hostel, writing and drinking beer. You spend a day exploring small villages in central Turkey. It’s a grand adventure that we both enjoy.

When we return from Turkey, we agree that we should travel together in Europe on a regular basis. But life gets in the way.

It’s Spring 2017. It’s been five years since our trip to Turkey. We’re ready travel together once more. After a year of talking and planning, you and I and Kim have plotted a month-long driving tour of Spain. Mostly, we’re going to make it up as we go along — just as we did before. We spend a Saturday evening finalizing details over a bottle of red wine. “I’ll start booking places next week,” I say.

But on Monday, you phone me. “J.D, don’t start booking yet,” you say. “This is the thing. I have cancer. I’ve been getting some tests and the results just came back. I have esophageal cancer, and I need to start treatment immediately. I can’t do the trip.”

My heart sinks — not for me, but for you. It’s the family curse. Grandma died of cancer. Your father died of cancer. My father died of cancer. Your brother died of cancer. All of us Roth males live in fear. We’re waiting for the day we learn that the curse has struck. And now it has struck you.

It’s Summer 2018. The doctors have been treating your cancer with immunotherapy. You and I grab the dog on a Wednesday morning and drive to the Oregon coast. You tell me all about your cancer, its survivability (bleak!), and the things you still want to do.

“I want to travel, J.D.,” you say. “You and I still have time to see the world.”

Your prognosis waxes and wanes. Some days it seems like you’ll live for years. Others, it seems like you have only weeks. Still, we manage to plan and execute a family trip to Europe in December. Your brother and three members of his family join us to explore Christmas markets in Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic, Switzerland, Germany, and France.

After your brother’s family returns home, you and I travel together for a week. Against your protests, I pay for us to ride the Glacier Express across the Swiss Alps. It’s too expensive for your frugal nature. But you love it. You are in awe. “J.D.,” you tell me later, “I’m so glad you made me do that. It was one of the highlights of my life.”

It’s May 2019. You and I are in the middle of a two-week tour of northwestern France. We’re making it up as we go along, as we like to do.

We spend a night on the island of Mont-Saint-Michel. You love it. We spend a night at Fontevraud Abbey, where we eat in the Michelin-star restaurant. You do not love the meal. The food is fancy but you are unimpressed. It’s too expensive. You cannot believe that I would spend money on this.

As we drive across France, our discussions are deep and weighty. You are weak and tired. Your mortality is heavy on your mind. Like me, you are filled with self-loathing — the crime you committed in your youth is always on your mind — so we talk at length about what makes a person good and what makes a person bad. Does one mistake define a life? How can you forgive yourself for the wrongs you’ve done to others? Neither of us has any solutions, but it helps to talk about these things with someone you trust.

It’s COVID times. You make yourself scarce. You are immunocompromised, so you’re unwilling to take risks. You are angry at your brother and his family because they don’t take COVID seriously. You vent your frustrations to me. You love Bob but this is causing a real rift in your relationship.

You continue your treatments — chemotherapy and others. Often, these treatments leave you drained and exhausted. You cannot even bring yourself to play Everquest. (You’ve been playing Everquest for nearly twenty years. You have a regular group that you play with. The game is a big part of your life.)

“Make some videos for me,” you say. You tell me this again and again. So, I make some videos for you.

I record myself playing Hearthstone. I record myself playing World of Warcraft. I record myself playing Civilization. When you don’t have the strength and focus to play games yourself, you watch me playing my games. I have no idea why you find this appealing, but you do. So, I continue to record videos for you.

It’s December 2021. You’ve grown much weaker. You are tired all of the time. It’s a struggle for you to walk. Still, you’re doing your best to live life as normal.

“I want to visit you and Kim in Corvallis,” you say. You drive down one Saturday and bring with you boxes of craft supplies. We spend hours building Christmas ornaments and decorations. In the evening, you introduce us to “The Great British Baking Show”.

The next Saturday, I drive up to Portland. You and I spend the day baking Christmas cookies. You’re weaker even than seven days ago, so you sit at the table and mix ingredients. I do all of the moving around.

“I think I’m going to leave my coins and cards to you,” you say. I’m uncomfortable with the conversation.

“Whatever you’d like,” I say. Over the years, you and I have continued to play Magic: The Gathering. You frequently play online. I play only when you and I attend “pre-release” tournaments. Maybe once each year, we’ll spend a Friday night with other nerds, playing Magic in local game stores. You remain a better player than me, but my skills are improving. I rarely lose anymore, but I don’t win much either. I earn a lot of draws.

It’s 11 February 2022. We’re packing your apartment. You’ve decided to move to Canby so that you can be closer to your brother and closer to the box factory. You and I are sifting through 21 years of Stuff. We’re creating a pile to donate. We’re stuffing boxes with clothes and mementos. Mostly, we’re packing your collections.

You have boxes and boxes of Magic cards. You have boxes and boxes of ancient coins. You have travel souvenirs. You have old computer games and manuals. You have children’s books. You have crafting supplies. You have far too much food for a single guy — and most of that food is long expired.

As we pack, we reminisce. We talk about the things we’ve done together. We talk about the things we want to do — the things we wanted to do. You show me your new fish. You’ve always loved aquariums. During the 1990s, you and I both set up aquariums at the same time, but we lost interest after a few months. Now, at the end of your life, you’ve decided you want to keep fish again. You enjoy telling me all about them.

It’s 26 February 2022. I’ve returned to help you pack. It’s slow going because you have no stamina. You find it difficult to make decisions. You are having trouble breathing. “Hector says I should go to the E.R. when I have trouble breathing,” you say, “but that seems excessive.”

After two hours, though, you’ve changed your mind. You ask me to drive you to the hospital, so I do. The pneumonia you had in January has returned. And the doctors tell you that the reason you’re having so much trouble breathing is that your left lung has collapsed.

It’s 04 March 2022. I’m at your apartment to help you finish packing. You are scheduled to move the next morning. The phone rings. It’s one of your doctors. You put him on speaker so that I can listen. You are seated on the sofa, your head bowed. As the doctor talks, you rock back and forth. Back and forth. Back and forth.

The doctor tells you that a feeding tube is not an option. “I’m sorry,” he says. “We can’t take the risk. The procedure is likely to kill you.” The doctor is audibly uncomfortable, yet he spends twenty minutes talking you through what comes next.

“I know this hurts to hear,” he says, “but you only have a few months left. Maybe a few weeks. It’s hard to say.” In reality, your life will end in 53 days.

“At this point,” the doctor says, “you should make your life about you. You should eat what you want to eat. You should drink what you want to drink. You should go where you want to go. You should see the people you want to see.”

You rock back and forth. Back and forth. Back and forth. “Thank you,” you say. “I understand.” After the call has finished, you sit in silence for a few minutes. I watch from the kitchen.

“Well,” you say. “I guess we should finish packing.” So we do.

I spend the night at your apartment. This is the first of 29 nights I will spend with you during the final 53 days of your life. From here on out, either your brother or I — often both of us — will be with you nearly all of the time.

It’s 07 March 2022. Yesterday was your 58th birthday. Today, we are unpacking at your new apartment. In a strange twist of fate, it’s the other half of the duplex you and I rented together in 1991.

You’ve set up three aquariums in the apartment, including one devoted only to Mbuna cichlids from Lake Malawi. That tank is currently home to six 34-cent goldfish, but you and I will gradually purchase nineteen cichlids over the next few weeks.

Your brother and his wife come over to help us unpack the kitchen. You sit in your walker and sort the boxes. You hand food to us. Audrey handles the food you’re keeping, tucking it into cupboards. Bob boxes some food to take home. I box the rest for me and Kim.

After Bob and Audrey leave, you begin experiencing severe chest pains. I drive you to the emergency room. You and I spend the night in the E.R. while doctors perform a variety of tests. I show you the videos I’ve made of our trips to Turkey and France.

These videos take your mind off your situation. I promise that I’ll finish the video of our family trip to European Christmas markets, but I never get the chance to do so. You’re discharged at five and we head home.

It’s 13 March 2022. You and I drive around Portland to look at fish. Your aim is to have 25 cichlids in your 90-gallon tank, but we start with six.

In the afternoon, Bob and Hector come over. The three of us have planned an important conversation with you, and you can smell it from a mile away. “You’re taking away my keys, aren’t you?” you say. Yes, we are taking away your keys. Driving has become dangerous for you. But that’s not all.

Hector asks if you’ve considered hospice. You become defensive. You don’t want to do hospice because you’re afraid that means surrendering to the disease. You don’t want to surrender. You want to fight. You want to continue driving to the E.R. whenever you have a problem.

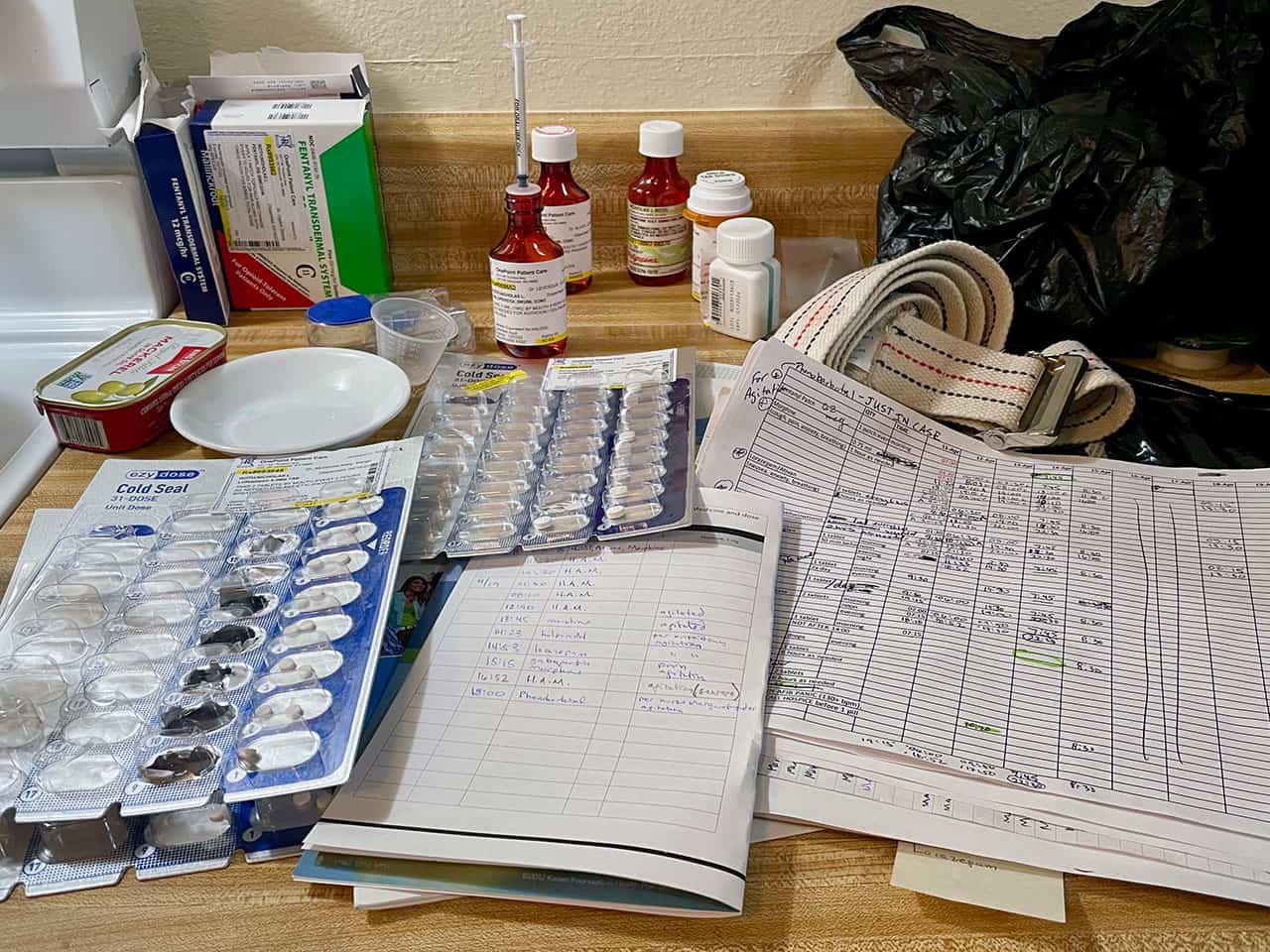

Bob and Hector and I know this isn’t a workable solution. We try to talk some sense into you. You are resistant. You and Hector bicker like an old married couple. In the end, though, you agree to meet with hospice to learn more about it. By the time I see you next, you have enrolled in a hospice program. It makes everything so much easier.

Over the next six weeks, we all come to appreciate the hospice nurses and volunteers. They’re amazing.

Also over the next six weeks, you have us watch hundreds of hours of the Aquarium Co-Op channel on YouTube. The channel plays almost constantly on the living room TV. Eventually, you have me drive you to purchase a new $300 TV so that you can hear and see the Aquarium Co-Op videos better.

At first, I’m annoyed by the constant fish videos. In time, however, I grow to love them. They’re comforting. And the host (Cory) is precisely the kind of YouTube personality I’d like to be — only he talks about fish and I’d like to talk about health and wealth. Bob and Hector and I may be the folks providing the bulk of your in-person care, but you demand Cory as a constant presence too.

It’s 17 March 2022. We’re driving to Portland so that you can visit your friend Kathy — and so that you can buy more fish. We’re talking about all of the loose ends in your life. I ask why it took you so long to complete your will. I ask why you haven’t designated beneficiaries on your investment accounts. I ask why you haven’t made a list of your logins and passwords.

“I’m in denial, J.D.” you say. I tell you that I get it.

The conversation turns to your new apartment and all of the boxes left to unpack. “It would really help if you took some of this stuff down to Corvallis,” you tell me. “I keep saying it’s okay to take some of the boxes of coins and Magic cards now before I die,” you say. “Why don’t you do it?”

I shrug. “I don’t know,” I say. “I guess I’m in denial too.”

You grab my right arm, causing me to veer slightly as I steer. “Thank you, J.D.,” you say. “Thank you. I get it too.”

It’s 22 March 2022. I’ve been away for three days taking care of Real Life in Corvallis. I’ve just returned to Canby. You are surly and sour. You are in pain. You are uncomfortable. You are finding it difficult to breathe. You are taking your frustrations out on everyone around you, even those that you love. Especially those that you love.

I can see that Bob is frustrated. “How do you feel about buying some new fish?” I suggest.

“I feel great about buying some new fish,” you say. I drive you around Portland for four hours. You’re too weak to exit the car, so I go into the pet stores and film their selection of cichlids. Then I return to the car so that you can see what each store has in stock. Eventually, we buy two fish.

We’re near Uwajimaya, the Asian grocery store, and you decide you want to try to go in. We get you out of the car, change oxygen canisters, then find a shopping cart for you to lean on. It takes fifteen minutes to walk from the snack aisle to the deli section. The journey exhausts you.

It’s precisely midnight between 23 March and 24 March 2022. You call from the other room: “Hello? Help!” I spring from the couch. Bob leaps from his recliner. We’re by your side in seconds.

“I can’t breathe,” you whisper. Your voice is plaintive, desperate. Bob wraps his arms around you and lifts you to a seated position. I pull the Pittsburgh Steelers blanket off you and then turn the oxygen dial to five, the highest it can go. You sit on the edge of the bed, gasping.

“I can’t breathe,” you say. Bob whispers to you, stroking your bony back. I go to the kitchen to see what drugs we have at our disposal. We gave you an ativan when you went to bed at ten. You’re supposed to go a minimum of four hours between doses but I don’t care. I get another one for you. I draw some morphine.

“I can’t breathe,” you say as you take the drugs. Bob calls the hospice nurse. It’s Tori, which gives me a sense of relief. Tori is awesome. She asks for your symptoms. She asks what drugs you’ve had during the past 24 hours.

“He’s on his fentanyl patch, of course,” I say. “He’s had two ativan in the past two hours. He’s had eight doses of morphine in the past day, but he hasn’t had any since six in the evening. He refused a dose at eight and again at ten.”

You don’t want to take the morphine. It makes you tired. It makes you muddle-headed. It makes you feel like you’re losing. In the afternoon, you blew up at a different hospice nurse. “I thought you guys were supposed to make me comfortable,” you barked. “Well, I’m not fucking comfortable.” When she suggested you take more morphine, you protested. “I watched when we gave my brother more morphine and he slipped away. The same thing happened with J.D.’s dad.”

“I can’t breathe,” you say, and Tori promises to call the doctor in charge of your case. The wait is agonizing. You can’t breathe. You can’t breathe. You can’t breathe. Tori calls back a few minutes later and tells us to increase the morphine.

“Give him another dose now,” she says. “In an hour, give him a double dose. Going forward, that’s the new dosage.”

Soon, you can breathe. The ativan relieves your anxiety. The morphine relaxes you. Bob lays you back on the bed and covers you with your Pittsburgh Steelers blanket. He and I sit in your bedroom, silent. We watch as you breathe. When you fall asleep, he returns to the recliner and I return to the sofa. We struggle to fall back asleep.

It’s 27 March 2022. You’re feeling stronger. Not strong, but stronger. You tell me that you’d like to go to the Coast, so we do.

You had harbored a hope of seeing Europe once more before you died. COVID dashed those hopes. You moderated your dreams, telling me that instead you’d like to make it to Atlanta to visit the Georgia Aquarium. That’s another dream that will never come true.

You decided that you’d be content if you could simply see the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport. Even that dream looked impossible for a few days. Now there’s a window of opportunity, so we seize it.

On the drive, we talk about music. I explain at length why I am such a fan of Taylor Swift and her music. “I hear what you’re saying,” you say, “but I just can’t get into her.” You’re a creature of habit. You like what you’ve always liked, and that mostly means classic rock.

As we drive, we take turns asking Siri to play songs on the car stereo. We steer clear of Taylor Swift and focus on the music you like. We listen to:

- Kansas – Dust in the Wind

- Mountain – Nantucket Sleighride

- Grand Funk Railroad – I’m Your Captain (Closer to Home)

- Neil Young – Old Man

- Trio – After the Gold Rush

- The Decemberists – Crane Wife

- Pearl Jam – Just Breathe

- James – Sound

- CSN – Southern Cross

- Jefferson Airplane – White Rabbit

- Deep Purple – Hush

When we reach the aquarium, you’re too exhausted to go in. I park in the sun so that you can be warm. You sleep in the car for an hour while I sit outside watching the Portland Timbers game on my phone. When you wake, you feel better. We get you in the wheelchair for the first time, and I push you around for 90 minutes so that we can look at the fishes.

Afterward, you ask me to stop at the candy store. We spend $100 filling bags with salt-water taffy, almond roca, and chocolate-covered twinkies. I think it’s been a long day and that we should head home. You don’t want to go home. You want to see more of the coast.

I drive slowly along the shoreline. I drive through the touristy parts of town. I drive along the shoreline again. You’re not hungry, but you want to get fish and chips. We stop to look up the best fish and chips spot that’s open at 6 p.m. on a Sunday night. It’s located in a strip mall 45 minutes north.

The manager is friendly and accommodating. When you tell him you’re cold, he brings you a hot chocolate. You drink your cocoa with a bowl of clam chowder. I have one beer with some fish and chips. I give you one piece of fish. You think the food is delicious. As I’m wheeling you out the door, you make me stop and call over the manager. You tell him it’s the best fish and chips you’ve ever had.

On the drive home, you sleep. When we reach the apartment, you’re too weak to climb into bed on your own. I have to lift you. As I turn out the light, you whisper, “Thank you, J.D. Thank you for everything.” I sit on the couch and cry.

It’s early morning 29 March 2022. The past 24 hours have been rough. You cannot walk without assistance. Your cannot find the words you want. You cannot get enough air. You go to sleep early.

Then, for no apparent reason, you wake at 2:30 and you are almost completely your old self again. You walk to the kitchen and rummage through the fridge. You pour a glass of chocolate milk. You ask to watch a movie.

I choose Arrival. “It’s a beautiful film,” I tell you, forgetting that the beginning also features a death like the one you’re experiencing. As we watch, I try to explain some things because I know this is the only time you’ll ever see the film. (And, in fact, it may be the last film you ever watch.)

“This story is about memory,” I tell you. “And time. And how the two are interwoven. It’s sort of non-linear at times.” When the aliens appear and begin communicating with their circular “sentences”, I tell you this is the central metaphor of the film.

You are awake and engaged for the entire movie. You find it fascinating. You ask questions. I give you answers. When the movie is over, you want a bowl of ice cream. You get up unassisted, pull the vanilla ice cream from the freezer, then add some strawberry syrup to several scoops of the stuff. You wolf it down.

“What should we watch next?” you ask.

“Dude,” I groan. “I need some sleep. I need to drive home in a couple of hours.” So, we go back to sleep. But as I drift off, I’m filled with regret. What am I doing? Why am I sacrificing this precious time with you? Sure, I’m tired, but so what? All your life, you’ve said, “You can sleep when you’re dead.” Well, you soon will be dead — I can sleep then.

I look over to see if you’re awake, but you’re not. You’ve nodded off in your recliner. I’ll simply have to savor the three hours I just got to spend with the normal you. (This moment and this film also inspire me to start documenting these moments with you, and those moments become this blog post.)

It’s 31 March 2022. After 48 hours in Corvallis to rest and recuperate, I drive back to your apartment to relieve your brother. I’m hopeful that you’ll be just as awake and alert as you were two days ago. You’re not. In fact, things are grim.

You barely respond when I greet you. When I ask you questions, you gaze at me vacantly. When you do respond, it’s a guttural whisper or nonsensical steam of consciousness.

“What about the cigarette butt?” you ask as I clean the coffee table.

“What?” I say, looking around. “What cigarette butt?” Nobody in your life smokes.

“What about the cigarette butt?” you say, pointing to the coffee table. “The white one. What about it?”

Nothing you say over the next hour makes any sense. “Look at her eyes. She looks like a bug. Is the new girl in my medicine? The fish, the fish, the fish.” You have trouble completing thoughts. But even when you complete your thoughts, what you say is a sort of word salad. Sometimes I can puzzle out what you mean to say. Mostly, I can’t.

You become restless. You remove your oxygen tube and attempt to stand. I give you support. I walk you to the kitchen. You open the refrigerator. “Hold on,” I say. “I’ll get you a chair to sit in.” I let go of you for only a moment — for only enough time as it takes to lean over and grab a chair from the table — but in that moment, you collapse to the ground. I manage to slide partway under you in an attempt to break your fall.

“Wow,” you say. Yes, wow. Fortunately, neither of us is hurt. It takes several minutes, but you manage to crawl to your hands and knees, and from there I’m able to lift you to standing. This time, I don’t let go. We get you into the chair. You eat some seafood salad and some smoked salmon, then I help you stumble back to your recliner.

“I’m not qualified to do this,” I text Kim. “I don’t know what I’m doing.”

You wake in the middle of the night to make lists. You make lists of things to do. You make lists of things to give away. You make lists of people to call. Because you’re a cheap bastard, you write your lists on the back of old envelopes or grocery bags.

You pick up a pillow from the floor and hold it to your ear. Then you hold it to your other ear.

“What are you doing?” I ask.

“Why is this so loud?” you ask. “Is it a bomb?”

It’s 03 April 2022. Nurse Diane shows you how to use adult diapers (or “briefs”, as she calls them). I expect you to be defeated by this. You aren’t. You’re surprisingly pragmatic about their use.

It’s 08 April 2022. I arrive back at your apartment after several days in Corvallis. You’re in much better shape than when I left you. You’re cheerful. You’re lucid. You’re engaged.

You ask to the go the tulip fields, so I pack your wheelchair and meds and oxygen tank, then we load into the car. There’s a large crowd at the flower farm despite being a cool Friday afternoon. Although you grew up maybe two miles from the tulip fields, you’ve never been here before.

I push you around from row to row. You admire the color. You point out your favorites. I point out mine. In the catalog, you note the bulbs I should plant for next spring. We suffer through a chilly rain shower, caught unprepared in the open. Then we admire the rainbow that follows. We can see both ends, but no pots of gold.

You’re hungry, so we drive to El Chilito, your favorite taco stand. It takes you twenty minutes to decide what to order: tacos dorados. When we take them home, you manage to eat one taco, but the rest of the tacos (and all of the chips) go to waste over the next several days. You have no appetite.

It’s 09 April 2022. After the hospice nurse visits, I tell you I’m going to go grab groceries real quick. Despite not having an appetite, you still dream of food. You are constantly having me add things to the shopping list: seafood salad, Greek yogurt, shrimp, apple juice, pretzels, black grapes (crisp, plump, juicy, and delicious).

I tell you I’ll be gone maybe thirty minutes, but you ask me to hold up. You want to go shopping with me. First, though, can I bring you the coupons from the mailbox? I do. It takes you thirty minutes to look through the flyers. There’s nothing that you want.

Then you decide you want to send flowers to your friend Kathy, who is also having medical problems. To do that, you need to know if she’s home, so you want to call Tom to learn Kathy’s status. You dial Johnny, your Everquest buddy, by mistake. You ask me if I can do something to make your phone less confusing. I try but it’s not the kind of phone I use, so I can’t understand the settings.

Three hours later — after several such digressions — we pack up and head to the grocery store. There, you’re immediately distracted by the Easter candy. You want malted milk chocolate eggs. We find them. Then it takes more than an hour to work through your short list of groceries. You’re fussy. You want to chat with the workers and customers. When the developmentally disabled fellow offers us help, you tell him you like his accent. He doesn’t have an accent. He has a speech impediment.

Later in the evening, you decide that it’s time to do a water change in the 90-gallon cichlid tank. Before we do the water change, you want to vacuum the gravel. You’re not happy with how I’m doing the job (it’s the first time I’ve ever done it), so you stand to do it yourself.

“You shouldn’t be standing,” I say. “And you should be wearing your oxygen tube.”

“If you’d do this right, I wouldn’t have to stand,” you tell me. I fume inside, but let it pass. This, I remind myself, is why I aborted my return to the family box factory: I couldn’t abide your need for perfection from everyone (except yourself). My anger passes quickly.

You sit back in the wheelchair, then bend over to pick up a book. Immediately, you bolt upright.

“Something’s wrong,” you say. “I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.” I scramble to get the oxygen re-attached. I dash to the kitchen for the morphine. I grab my phone.

“Call Hector,” you tell me. I call hospice instead. “Goddamn it, J.D., call Hector,” you say. I bring your phone to you so that you can call Hector while I speak with the hospice nurse.

Hector tries to calm you through breathing exercises. Hospice has me administer lorazepam and haloperidol. They’ll relieve your anxiety and help you breathe — but not for fifteen minutes. You’re panicking. “Where are you, Hector?” you ask. “Why aren’t you here?”

“I’m home in Vancouver,” he says.

“You guys are useless,” you say. “Where’s Bob?”

“Your brother is at the coast,” I tell you. “He’s a couple of hours a way.” Bob and Audrey have spent the day with friends. They’ve just finished eating fish and chips at the same place you and I visited a couple of weeks ago.

“I’m surrounded by fools,” you say. “I can’t breathe!”

The oximeter says that you can breathe. Your oxygen saturation is fine. Your pulse, on the other hand, is bizarre. It’s 40. Or 220. Or 40. The reading is inconsistent, but it’s always one of those two. I try to take your blood pressure with the automatic cuff. I get nine consecutive errors. Some of these are because you’re agitated and won’t sit still. But why am I getting the others?

At last, I get a reading: 60/44. I write the number on my hand. I call hospice again. “He’s in A-fib. You’ve exhausted all your tools at home,” the nurse tells me. “Call 911.”

I call 911. I’ve never called 911 before. They send an ambulance. I’ve never been involved with an ambulance or paramedics before. They pull off your shirt and attend to you. They ask me questions. They verify your POLST. They load you up and drive you to the hospital. I follow a few minutes behind.

As I drive, I call your brother. He’s in Salem, on his way back from the coast. He’ll meet us at the hospital.

At the hospital, I am surprised to learn that they’re releasing you almost immediately. Bob arrives, and we chat with the doctor in the emergency room. He tells us you had an attack of atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response — A-fib with RVR. The paramedics shocked you with cardioversion to “reset” your heart. You can go home now.

We’re surprised but pleased. You spend less than twenty minutes total in the emergency room. I drive you home. You ask to listen to Queen. Siri makes some odd song choices. First, The Show Must Go On: “Does anybody know what we are living for?” Then, You’re My Best Friend: “Oooh, you make me live.” Finally, Who Wants to Live Forever. I wince at the playlist, but you don’t say anything.

It’s 10 April 2022. The hospice nurse is here to follow up after last night’s excitement. You’ve been drugged and out of it for the past twelve hours. You ask me to take you to the toilet.

“J.D.,” you whisper as I help you to the commode. “I’m afraid. I don’t think I’ll make it past today.”

After the nurse has gone you fall back asleep. You sleep for 33 of the 36 hours following your visit to the emergency room. At one point, you wake with a coughing fit. I’m by your side with morphine. You dutifully take it.

“How long?” you ask.

“How long what?” I say.

“How long is there left to live?” you ask.

“I don’t know,” I say, stroking your back. The answer to your question is: fifteen days. You have fifteen days left to live. But truly? When it’s all over, we’ll be able to look back and say that your weekend trip to the E.R. was the true beginning of the end. From here on out, you’re not so much living as you are dying.

It’s 11 April 2022. Hospice nurse Mary arrives. She’s your primary nurse, but I’ve never met her. She’s even more amazing than Tori. Even more amazing than Helen. She can tell that the mood in the house is gloomy. Our morale is dismal. You are defeated. You are waiting around to die.

Mary is having none of it. “I’m not supposed to say this sort of thing,” she confides, “but you are the one in charge. You are the one calling the shots. Who cares what the doctors tell you? If you want to fight, fight.”

“I do want to fight,” you mutter.

“Then we’re here to help you,” your brother says.

Mary’s visit lasts less than an hour, but has a profound effect. The morale in the house has gone from low to high. We have a plan. We’re going to fight.

This enthusiasm is short lived. You lapse into delirium. You are frustrated and angry. You sleep most of the time. Bob and I wheel you from room to room at your request, but you have no energy to do anything. You eat little. Lucid conversation becomes rare.

At one point, you and I attempt to watch As Good As It Gets. It’s been your favorite movie for decades. You think Jack Nicholson is hilarious in the film and you frequently quote Melvin Udall’s lines, such as:

Where did they teach you to talk like this? In some Panama City “sailor wanna hump-hump” bar? Or is it getaway day and your last shot at his whiskey? Sell crazy someplace else. We’re all stocked up here.

But you don’t have the energy and attention to watch the movie. You fall asleep after twenty minutes. When you wake an hour later, you’re confused. “What are we watching?” you ask. I don’t try to explain.

It’s 18 April 2022. You have returned from a weekend in “respite care”. You volunteered to stay in a hospice facility for a few nights so that Bob could celebrate Easter with his family and so that I could celebrate my ten-year anniversary with Kim.

Now, though, you are completely disoriented. You don’t know where you are. You don’t know why you’re medicated. You don’t know why you’re confined to bed. You repeatedly try to climb down, but you lack the strength to do so. You are agitated and hostile, accusing me and Bob of playing a joke on you.

It’s 19 April 2022. You remain agitated. You curse us. You demand that we get you out of bed. You demand that we take you to the kitchen, then to the living room, then outside to look at your flowers, then inside because it’s too cold, then outside again because you’ve forgotten we were outside just five minutes ago.

Bob attempts to get some work done, but it’s impossible. For ten hours, you are agitated and irritable. You are delirious. You try to bite Bob. You throw feeble punches at me. You are clearly frustrated, like a caged animal who does not understand its plight.

You have a few brief moments of lucidity throughout the day. In these, you tell us that you love us and appreciate us.

Mostly, though, you are lost. “What happened?” you ask. “You have cancer,” we say. “I do?” you say. “Will I live?” you ask. Bob and I shake our heads.

Your agitation grows throughout the day. Again you accuse us of playing a cruel joke on you. You call Hector and berate him for pranking you. You call Kathy and do the same. Bob and I are at our wits’ end. We call hospice and they send out Nurse Margaret.

Nurse Margaret gets permission for us to administer phenobarbital, which we do at six in the evening. Within fifteen minutes, you have calmed. Soon you grow groggy. You fall asleep.

It’s 20 April 2022. You wake grumpy. Bob and I are reluctant to administer the phenobarbital because it knocks you out. But when we don’t administer it, you are agitated. He and I discuss things with the hospice nurse and decide that we have to use the phenobarbital. Before we give you the next dose, however, we ask if you want anything to eat. “Eyes uh,” you say.

You want ice cream. I bring you a bowl of chocolate gelato. Bob feeds you three bites before you fall asleep. This is the last thing you will ever eat.

Hector comes to visit. So do your nieces and nephews. Despite the voices and laughter throughout the apartment, you do not stir.

In the late afternoon, you wake for a few moments. There’s a crowd around your bedside. You look from face to face. It’s not clear that you recognize us. “Nick, how are you doing?” Hector asks. “It’s me, Hector.”

Hector points to your niece. “Do you know who that is?” he asks.

“Janissa,” you whisper.

Hector points to me. “Do you know who that is?” he asks.

“J.D.,” you whisper.

You make a move as if to hold Janissa’s hand, but when she reaches out you flip your middle finger and grin.

These are the last words you ever say. This is your last conscious action. You fall back asleep. You will never wake again.

For the next several days, Bob and I sit by your bedside. We share childhood memories. He talks to me about his faith. I talk to him about my lack of faith. Bob plays hymns for you on YouTube. I play Taylor Swift. We watch the cichlids in your aquarium. Bob and I administer your care to the best of our abilities. We don’t really know what we’re doing but we love you and we do what we can. The hospice nurses praise us but we’re not sure we deserve their kind words.

Hector drives down to see you nearly every day. He spends hours at your bedside. He cleans and grooms you. He adjusts your position to make you more comfortable. He chatters at you. When Hector is there, Bob and I run errands. We shower. We eat. Other friends and family come to see you and to sit by your side.

When we’re bored, Bob and I begin doing the things we know will need to be done. We begin packing your stuff. We begin gathering account information and passwords. We begin cleaning the house. These actions no longer seem like a betrayal. They seem like acceptance.

I will come into your bedroom to find Bob asleep at your side, his hand in yours. Bob will come into your bedroom to find me asleep at your side, my hand in yours.

I sleep in a recliner next to your bed. Each morning, my back is sore but I don’t care. I want to be close enough to hear changes in your breathing. Some nights, Bob sleeps in an office chair next to your bed.

We await the inevitable.

It’s 25 April 2022. Bob wakes me at five minutes before seven: “I think he’s going.”

Your vitals are weak and erratic. I wake your nieces and nephews, who have stayed the night with us. I administer your meds, which are due at seven anyhow. Your vitals stabilize. We breathe a sigh of relief.

The family spends the morning sitting around your bedside chatting, much as we have all week.

Nurse Mary comes at ten for your daily visit. The kids leave the room while she and Bob and I talk about your condition. We adjust your bed. We re-arrange the cushions. We take your vitals. Taylor Swift’s “Red” is playing in the background.

Mary removes your oxygen mask in order to clean your mouth. She and Bob lean in close. I am standing at the foot of your bed. Your oxygen saturation drops from 67 to 37 but your pulse stays steady at 105. The three of us focus on your mouth as Mary explains what she’s doing with the cotton swabs. She wipes with one swab. She wipes with a second. I glance down at the pulse oximeter. There are no numbers there. The pulse line is flat. I look at your chest. You are no longer breathing.

“He has no vitals,” I say.

Bob and Mary step back from your bed. “He’s gone,” says the nurse. And you are. You are gone. It is 10:15 on a Monday morning, and — just like that — you have left this world.

You were my cousin. You were five years older than me. You and I shared similar temperaments, similar interests, similar philosophies. We read similar books. We played the same games. We confided our deepest secrets with each other. We encouraged each other. We called each other out on our bullshit. You taught me much about life. I did my best to teach you. You were my cousin. You were my friend. Get Rich Slowly would not exist without you.

Howdy, folks. I don’t have any personal finance news for you today because my life continues to be in one of two states.

- I spend three or four nights at Duane’s house, helping to care for him. I buy him food. I prepare him food. I help him walk from room to room (because he cannot reliably do this himself anymore). I administer his drugs. I feed his fish. I take him on “field trips”. We watch the Aquarium Co-Op channel on YouTube. Or…

- I spend three or four nights at my house, mostly sleeping but also rushing to get as many household chores and errands done as possible. I buy groceries. I (slowly) work to build a fence. I water plants. I walk the dog.

This has been my life for the past six weeks, and will continue to be my life until the inevitable conclusion of this adventure. While I’m not looking forward to The End, I will say that I’ve learned a ton from this process. I’ve grown even closer to Duane (at least when he’s not in a narcotics-induced fog) and I’ve surprised myself with my ability to provide hospice care. Who knew?

So, that’s the life update.

I do have occasional snatches of free time, usually as I’m falling asleep at night. But rather than use those to read and write about personal finance, I use them to mindlessly watch YouTube videos. Here are a few recent favorites.

First, from the vlogbrothers, here’s a nice little four-minute mediation about seeing both sides at the same time. Like the narrator here, aging has led me to see the world as shades of grey rather than black and white. Things can be both good and bad at the same time.

Second, during a text conversation yesterday with Piggy and Kitty from Bitches Get Riches, I was introduced to the TierZoo channel on YouTube. Apparently this has been popular for five years, but I’d never heard of it. It’s incredible. At first, you think it’s funny — because it is funny — but you gradually realize it’s both interesting and educational. Here’s TierZoo ranking the best cats, for instance.

Lastly, here’s an hilarious three-minute video that substitutes Elmo for Paul Atreides in Dune. I was lukewarm on the recent Dune adaptation the first time I saw it. The second time, I liked it better. Recently, I watched it on my iPad while wearing high-quality headphones. Holy cats! I enjoyed it so much more. In fact, I’ve come to think it’s a masterpiece. And so is this little gem…

That’s it. Just a quick check-in. I’ve done zero work on Get Rich Slowly (or anything else) for the past six weeks, and there’s no work likely to happen for the foreseeable future. As I say, it’s 100% caring for Duane and time reclaiming sleep and mental energy so that I can go back and do it again.

I hope you all are doing well!

p.s. Okay, one more thing. This time off has given me a chance to think about a lot of things. Duane and I used to have long, deep discussions about Quality, for instance, inspired by Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. What I want for this site is a focus on Quality. I read this 1992 letter from producer Steve Albini to the band Nirvana and was impressed on how much Quality mattered to Albini. Well, it matters to me too, and I’ve been neglecting it for a while. Time to un-neglect it.

Monday, I drove north to help my cousin, Duane. We moved him out of his apartment last weekend and into a smaller place close to family. As a result, everything is in chaos. He’s living out of boxes. At this late stage, his cancer affects every aspect of his life, and that includes his ability to sustain prolonged physical activity — such as setting up a new home.

I spent Monday afternoon unpacking his kitchen, buying groceries, installing his internet and television, and so on. In the evening, Bob and Audrey came over (Duane’s brother and his sister-in-law). The four of us sat in the kitchen and sorted the boxes of food into three piles: Duane’s pantry, going home with Bob/Audrey, going home with J.D.

When we were done, Duane insisted that we enjoy some birthday cake. He turned 58 on Sunday, and some friends had brought him a fancy carrot cake from a 100-year-old Portland bakery. Duane couldn’t eat any cake himself (he can’t eat or drink much of anything anymore), but he wanted us to taste it.

After his brother left, Duane and I began preparing for bed. “Tomorrow,” I said, “we’ll replace the water in your fish tanks and get the last of the stuff from your apartment. Plus, anything else you want to do.”

Duane was sitting on the edge of his bed, half undressed. I could see that he was still in pain.

Duane had been in pain all day. He’s in pain constantly now, but this was a new pain. He woke on Monday with a dull ache in his chest, one that intensified throughout the day. His meds were no help. He’d upped the dosage on his oxycodone to no avail. He’d even tried some morphine, but that didn’t help either.

“Are you okay?” I asked. We ask that of him a lot lately, although it seems a little silly. Of course he’s not okay. He’s dying. What we actually mean, of course, is: “Is there anything you need right now?”

“No, I’m not okay.” Duane whispered. “I need you to drive me to the emergency room.” So I did.

We reached the hospital at 10:30. I thought we’d have to wait to be seen, but a nurse fetched us before I’d even wheeled Duane to the waiting area. Hospitals don’t mess around with chest pain.

“I’m not having a heart attack,” Duane told the nurse. “It’s my cancer. I don’t need an EKG.” But, of course, they ran an EKG anyhow. It’s protocol. Then, over the next several hours, they also took x-rays. They gave Duane a CT scan. They pumped him full of fluids. They drew blood. They did a urine analysis. And, most importantly, they hooked him up to a morphine drip.

The morphine drip slowly caused the pain to subside.

We had a bit of a scare at two in the morning, not long after the staff had started the morphine. Duane’s pulse leapt from 85 to 145 and his blood pressure dropped from 95/65 (which seems low to begin with) to 75/60. This state lasted about twenty minutes. We were both a bit panicky. The nurse calmed us down, though, and soon things returned to normal. (Or “normal”, I guess I should say.)

Despite the intermittent nurses and doctors and tests, mostly Duane and I spent the night alone in the room, chatting.

He lay in his bed. I sat on a folding metal chair. We talked about hospitals. We talked about computer games. We talked about travel. We talked about fish. We talked about death.

“I’m sorry you have to be here,” Duane said at one point. “I had hoped that you and I could have Quality Time together. I wanted us to play Diablo II. I’d hoped we could visit the Atlanta aquarium. I didn’t mean for us to be doing this.”

“Don’t worry about it,” I said. “This is Quality Time. It might not be what you wanted, but it’s Quality Time.”

Duane thought about that for a moment. “I guess you’re right,” he said. “It’s Quality Time.”

“Here,” I said, pulling out my iPad. “Let me show you what I made for your birthday.” For the next hour, we watched videos of our trips to Turkey and to France. We reminisced about our travels and laughed at some of our misadventures. We enjoyed Quality Time.

At five o’clock, as Duane and I were both beginning to nod off to sleep, the doctor decided to discharge him. There’d been some debate about whether or not Duane should be admitted to the hospital again. He was just there last week with another bout of pneumonia. (Or, more precisely, the same bout of pneumonia he’d had in January but which apparently had not gone away.) Ultimately, the doctor felt there was no benefit to be had, so he sent Duane home.

“I guess we won’t be accomplishing all the things we’d planned for today,” Duane said. The first light of dawn was creeping into the sky. “That sucks. I’ve got to get my stuff out of that apartment.”

“We’ll get it done,” I said. “We have until the weekend. You and I both need to sleep now, but I’ll be back up here on Thursday. I’ll make it my priority to get the apartment finished for you. And if we have time, we can tackle other tasks on your list too.”

After dropping Duane at his new place, I drove 90 minutes home to Corvallis (which I ought not to have done given how tired I was) and then slept most of yesterday. I’ll use today to triage the stuff I need to get done here at home. Tomorrow, I’ll drive north again to spend more Quality Time with my cousin.

Here’s the thing. I’ve made a lot of mistakes in my life. My Book of Regrets is packed with pages and I spend far too much time re-reading it, re-living the things I’ve done wrong. But I do not regret the choices I’ve made this year.

I began 2022 intending to get fit and to work hard on Get Rich Slowly. I’ve done neither of those things. I’m still fat. I’ve barely touched this site. But I’m not squandering my time on computer games and anime either. Instead, my energies have been directed to my mother and my cousin. I have zero regrets about this decision. In fact, few things have ever felt so right.

I’ve spent a great deal of time thinking about this, actually, and I have a lot to say on the subject. I feel like this experience has imparted some clarity. (Clarity that expands upon my insights from November.) Eventually, I’ll probably write about some of what I’ve learned. But not now.

Now — and for the foreseeable future — I have one priority: While it’s still possible, I want to spend Quality Time with Duane.

Because I’ve been driving back and forth from Corvallis to Portland so much lately to attend to my mother and cousin, I’ve had ample to time to listen to audiobooks. I find that I’m actually grateful for the opportunity to “read” in this fashion. (Like many folks, the past decade has destroyed my attention span and ability to read for long periods.)

I’m currently reading Stephen R. Covey’s classic The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. (Five stars on Amazon in 5672 reviews!) I read the book once long, long ago — sometime during the mid-1990s. I’ve referred to it now and then as the years have gone by, but mostly I’ve forgotten its lessons.

Or so I thought.

In reality, it turns out that much of my life philosophy is similar to the precepts Covey covers. It’s shocking, in fact, just how much of my personal and financial philosophies align with those presented in Seven Habits. I haven’t consciously or deliberately emulated his teachings, but I’ve wound up in the same place nonetheless.

For those unfamiliar, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People are as follows:

- Be proactive. Take responsibility for your own life. Take the initiative and don’t simply accept what you’re given. (Here are my thoughts on becoming proactive.)

- Begin with the end in mind. Have a plan for your life. Know where you want to go — and why. Like me, Covey is a proponent of writing a personal mission statement.

- Put first things first. Sort out your priorities (which is much easier to do when you have an end in mind). Focus your attention on the things that are urgent and important. Covey’s “big rocks” metaphor comes from this section (see video below).

- Think win-win. When possible, seek mutually beneficial solutions to problems. Don’t be adversarial. Help others achieve their aims as you achieve yours.

- Seek first to undertand, then to be understood. Don’t be in a rush to be right. Listen to what others are saying. (Truly listen.) Practice empathy. I feel like this is a seldom-practiced skill in modern society, which is why I urge people to practice financial empathy.

- Synergize. Find ways to work with others in order to achieve mutual aims and accomplish things that you couldn’t do alone.

- Sharpen the saw. Make time for personal renewal. Keep your lifestyle balanced. Pursue self-improvement.

It’s also worth noting that apparently Covey is responsible for coining the terms “abundance mindset” and “scarcity mindset”. (That’s what Wikipedia says, anyhow. I’d need to do further research before I actually accepted this as a fact.) I too believe strongly that each of us should foster an abundance mindset, when possible.

While there’s much that’s the same between my philosophy and Covey’s, things aren’t completely identical.

Covey talks about dependence and independence, as I do, but he takes things to another level by discussing interdependence. I like this. Independence, Covey says, is superior to dependence. It’s better to be self-reliant than to depend on others to fulfill your needs. But, he says, it’s even better to work together to achieve common aims. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

I agree with him, but I haven’t (yet) incorporated this belief as part of my life philosophy. Perhaps I will in the near future.

Covey goes down some rabbit holes that I don’t find particularly important. (I just listened to a half-hour segment on the values that make up our personal “centers”. Meh.) Plus, he continually praises human beings as different in “kind” from other animals as opposed to different “in degree”. I disagree with him 100%. (I believe that humans are just another animal, and there’s nothing particularly remarkable about us other than we’re currently the dominant species on the planet.)

Small quibbles aside, I’m finding The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People to be a remarkable book precisely because its philosophy is so aligned with my own. When I read it at age 25, I dismissed it as self-help pap. I was wrong. Or, more precisely, I wasn’t ready to perceive its wisdom.

I’m not sure how my philosophy ended up so closely aligned with Covey’s. It’s very possible that reading this book 25+ years ago planted seeds in my subconscious that have grown over the years and now have produced fruit that resemble his. But it’s also possible that my beliefs are simply a by-produce of age and experience, that many people reach these same conclusions in time.

Anyhow, I’m eager to finish my work today at the family box factory. Once I run payroll and meet with our accountant, I’ll drive back to Corvallis. And when I do, I’ll listen to another 90 minutes of Seven Habits. I can’t wait!

Last Friday, I drove from Corvallis to Portland to help my cousin, Duane. Duane has been living with throat cancer for several years now, but in recent months things have grown worse. It feels like he’s preparing for the end. And that means he’s packing up his apartment (where he’s lived for 21 years!) to move someplace smaller.

We spent all of Friday afternoon sorting through his office. This was a challenge because (like most Roths) Duane is messy (and a self-proclaimed hoarder). Duane and I packed boxes and boxes of collectible card games, ancient coins, books on Greek and Roman history, and outdated computer games.

While we packed, we talked. Duane is my cousin, yes, but he’s also my best friend. Because we’re family and friends, I feel like we share a deep connection. We can call out each other’s bullshit without hurting feelings. We can sing each other’s praises without becoming obsequious. Most of all, we can talk about nerdy stuff like Magic: The Gathering, The Great British Baking Show, the ignorance of history in supposedly “historical” television dramas, and so on.

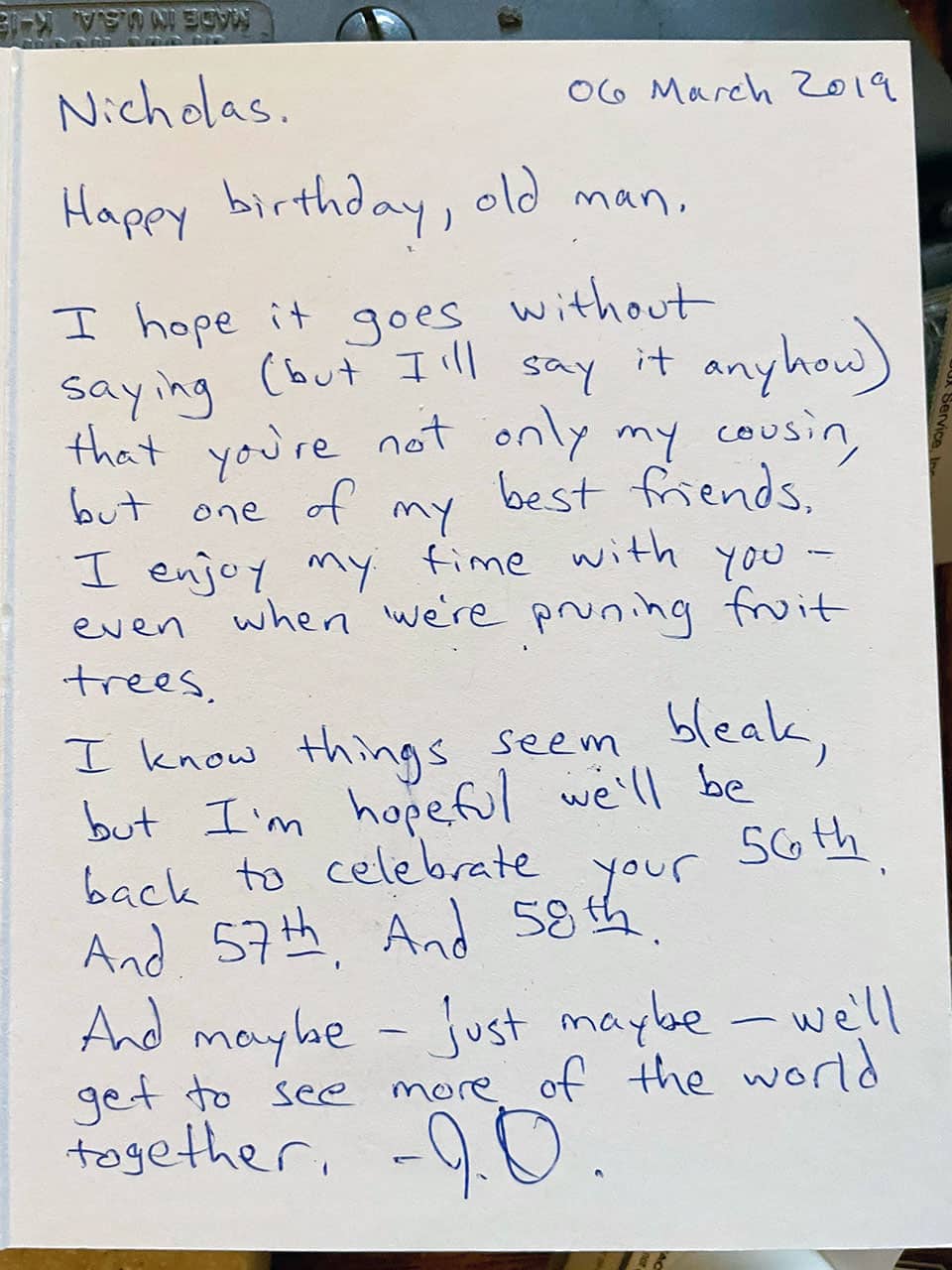

At one point, I found a piece of paper buried on a bookshelf. “Can I have this?” I asked. “I want to publish it on Get Rich Slowly.”

“What is it?” Duane asked.

“It’s your net worth from 1993,” I said.

Duane laughed. “Go ahead,” he said, and I gleefully tucked the page in my pocket. I love it.

![Duane's net worth from 1993 [notebok paper with Duane's handwritten net worth]](https://www.getrichslowly.org/wp-content/uploads/duane-networth-1993.jpg)

I love that his net worth lists assets like “Aquariums $100” and “Albums $100” (referring to his progrock record albums) and “Stamps $16,000”. Duane used to collect semi-official Canadian airmail stamps. Then he moved on to collecting ancient Green and Roman coins.

I also think it’s hilarious that Duane listed his $9 Texaco charge card as a liability. Nowadays, I wouldn’t bother with a debt so small. Thirty years ago, though, Duane did.

Although our work was non-strenuous for me, it took its toll on Duane. He recently finished another round of chemotherapy and is in a lot of pain. It’s a struggle for him to walk up stairs, to lift even the lightest objects. At one point, he pulled off his shirt to show me how emaciated he’s become. (He can’t eat solid food, so it’s difficult for him to consume enough calories. Drinking calories gives him nausea.)

“I’m so skinny!” he said.

“How does that make you feel?” I asked.

“Old,” he said. “I look like I’m 87, not 57.”

We began packing another box of ancient coins. “Hey,” Duane said. “If you get bored, I could use your help making a will.”

“You still haven’t done that?” I asked. Duane has been talking about making a will for months now. Maybe years.

“No,” he laughed. “I’ve been feeling better.” I knew exactly what he meant.

When Duane feels lousy, he’s motivated to plan for his impending demise. He thinks about writing a will. He thinks about finding a replacement for himself at the box factory. The problem is that once he begins to feel better again, he decides not to do anything. As a result, the family business still has no plan for accounting and bookkeeping once he’s gone. And, obviously, he still hasn’t written a will.

I shook my head. “Dude, you know that you should to write a will when you’re of sound mind and body. That’s exactly when you’re supposed to do it. You’re not supposed to wait until the very end.”

He laughed. “I know,” he said. “But I don’t like thinking about it.” Nobody does. Nobody does.

We didn’t get to the will last Friday, though. We got distracted talking about computer games. I left without helping him draft one. (I also left without a sketchpad and a houseplant he wanted to give me.)

“I really appreciate your help,” Duane said as I was prepping to leave. “It would have taken me weeks to do what you accomplished in a few hours. Thank you.”

“No problem,” I said. “And please, let me know if there’s anything else at all I can do. I know it might seem like you’re hassling me, but you’re not. I want to do this more than anything.” Earlier in the day, we’d talked about how much we appreciate each other and about our regrets. One of my deepest regrets is that I blew off my friend Sparky in the weeks leading up to his suicide in 2009. I didn’t know his death was imminent. This time, Duane’s demise seems clear, and I want to make the most of whatever time we have left.

Today, Duane sent me an e-mail. His follow-up appointment yesterday didn’t go well. His treatments aren’t working, and the doctor has nothing else to try. All that’s left is to mitigate the growth of the tumor. So, it’s very likely that I’ll be making lots more unplanned trips to Portland in the near future: to help Duane, to help the box factory, etc.

First, though, I want to help Duane draft a will. He doesn’t know where to start. Honestly, neither do I.

Okay, that’s not exactly true.

I’ve written about estate planning several times in the past, although not in many years. And behind me here in my office, I have shelves of personal finance books, including books on estate planning. Books like The Executor’s Guide to Settling a Loved One’s Estate or Trust and The AARP Crash Course in Estate Planning. (Most of my books are showing their age, however)

Meanwhile, I again need to put my 2022 plan for GRS on hold. I spent Monday and Tuesday this week diving into the long-awaited “de-design”. (I want to revert this site to a much more minimalist (almost “primitive”) look and feel. More on that later when I’m ready to reveal the new look.) I made some good progress, too. I’d hoped that by the end of this week, I’d have a design finished and ready to convert to a blog theme. Now I need to put this plan aside for more important things.

Fortunately, I find I’m not frustrated by any of this. I feel like I have the right attitude here, that I’m placing priorities where they ought to be placed. I’ll finish the GRS de-design at some point. For now, though, I’ll focus on family (and on the family business).

Before I wrap things up today, I have one request.

If you have any experience and/or recommendations regarding writing your own will, please drop me a line whether by email or in the comments below. I won’t get to this today — I need to tie up loose ends here at home so that I’m able to turn my attention outward — but I’ll probably start my research tomorrow. I’d love suggestions for books, software, and/or online resources for estate planning.

In return, I’ll do my best to collect these into a useful blog post here in the near future. Thanks!

Life has been lumpy lately. I’ve been dealing with some heavy stuff in my personal life — Mom, my cousin Duane, etc. — and that’s left me feeling low. Combine that with my natural inclination toward depression, and you’ve got a recipe for a gloomy guy.

That said, I woke up feeling great today. And that energy carried through as I had my regular Zoom call with Diania Merriam, the organizer of the EconoMe Conference.

Diania and I started these calls for professional reasons, but after nearly two years they’ve evolved into something else. Now they’re mostly a chance for us to help each other with our respective mental health struggles. During today’s conversation, we had an interesting digression about personal finance.

![Diania and J.D. chatting on Zoom [Screencap of J.D. and Diania on Zoom]](https://www.getrichslowly.org/wp-content/uploads/diania-zoom.jpg)

We were talking about how I need to get out of the house more. Because I work from home, I spend most of my time alone. It’s not good. Humans are social creatures, and that goes double for me. No wonder I feel shitty when I never leave the house!

Anyhow, Diania mentioned that she gets a lot of benefit from attending yoga regularly. And then she said something interesting.

“I’ve actually started cleaning the yoga studio,” she said.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Well, instead of paying $113 each month to be a member, I clean the yoga studio for two hours per week. In exchange, I get free membership. But you know the crazy thing? I find that I am much more motivated to attend classes because I’m cleaning the place than I did when I was paying money out of pocket. It gives me a sense of ownership. I look in the mirrors and think, ‘I cleaned that.’ I have a greater sense of buy-in.”

“That’s interesting,” I said. “Buy-in is so important. And it’s different for each person and each situation. I joined a gym last week. Kim and I have a sort of rudimentary home gym here in our basement, but in the four months we’ve lived in Corvallis, I’ve never used it. Kim has used it once. But now that I’m paying to belong to a place, I’ve been to the gym four times in the past week.”

“Do you worry that’s only because it’s new?” Diania asked. “Do you worry that you’re not going because of the money you’re spending, but simply because of the novelty?”

“I see your point,” I said. “But I’d like to believe it’s because of buy-in. I know that I enjoy exercising. And I know that a decade ago when I was paying $200 each month for Crossfit, I went to the gym four or five times a week. Because I was spending so much, I was motivated to go. I’m hoping that’s the situation here too.”

Diania and I talked about the problem with personal inertia. When we do things, it’s easy to keep doing those things — whether they’re harmful or helpful. We develop habits, we develop routines, and then we stick with them. The challenge then is to overcome what I’ll call “negative inertia” — being stuck in a rut — and replacing it with “positive inertia”.

Our conversation reminded me of my article about using barriers and pre-commitment to do the right things with your money. (Trivia: This is one of my favorite articles that I’ve ever written.) For me and many others, it’s vital to create barriers to bad behavior while simultaneously removing barriers to good behavior.

Here’s a funny/sad example.

I initially visited our local gym on November 11th. I took a tour, talked with the manager, and brought home two day passes for us to use. “I’ll be back tomorrow to join,” I told the manager as I left. But that didn’t happen. Instead, I got distracted by life. (Kim and I never even used our free day passes before they expired!)

Over the next few months, there were days that I very much wanted to go to the gym. I wanted to lift weights or to ride the stationary bike. I wasn’t able to do so, though, because I’d never completed the sign-up process. And the thought of completing the sign-up process was a psychological barrier. “I don’t want to mess with that,” I thought to myself several times. So, I never went to the gym.

Last Tuesday — nearly three months after touring the gym — I’d finally had enough. “This is a stupid barrier,” I thought to myself. “I need to remove it.” I stopped what I was doing, walked to the gym, and completed the sign-up process. Now, I’ve been to the gym four times (and will go a fifth later today) and Kim’s been twice. I removed the barrier and now I’m exercising.

But it’s not just removing the barrier. I’ve also created buy-in because I know I’m paying for my membership. This financial “investment” creates motivation to make use of the facility.

Now, I’m well aware that this isn’t always the case. Plenty of people sign up for gym memberships without ever using them. That’s because a financial buy-in isn’t always effective. There are other sorts of buy-in. For each change that you want to make, you have to figure out which type of buy-in will work for you.

In Diania’s case at the yoga studio, a buy-in of time was more effective than a monetary buy-in. “You know what, J.D.,” she said during our call this morning. “I’d be willing to bet that an investment of time and energy is almost always a more effective buy-in than a buy-in of money — especially for folks like you and me who have all the money we need.” I think she’s right.

Because Diania and I are fortunate that we don’t have to worry about money, a financial buy-in doesn’t always work. For us, time is generally more valuable than money. When we devote our hours and energy toward a cause, we feel more invested in it. But for somebody in different circumstances, the opposite might be true.

There are other forms of buy-in too. Sometimes we buy into things emotionally. Sometimes we do so intellectually. And so on. Each person and each circumstance is different, but the principle remains the same: buy-in matters. Buy-in creates motivation.

Diania and I briefly talked about the dark side of buying in: the sunk-cost fallacy. Sometimes we stick with things because of all that we’ve invested before. We base our decisions on the past rather than the future. We might, for instance, maintain an old friendship that has long since become destructive. Or we might hold on to a poor investment because of all the money we’ve put into it already. The process of buying in can encourage positive change, yes, but it can also lead us to cling to things we ought to let go.

As always, there are plenty of other changes I’d like to make in my life. Some of these are changes I’ve wanted to make for years. Why haven’t I made them then? Tough to say. But my conversation with Diania has helped me to understand that one tool I can use to foster these changes is to create some sort of buy-in.

Today, I want to share a small victory.

Like all humans, I have flaws. One of mine is that I hate confrontation. It’s a family thing. I’m not sure why, but none of us like conflict. Sure, this trait has some upsides. My brothers and I don’t get into a lot of arguments and fights with our family and friends. And when we do have conflict, we do our best to resolve things quickly.

But this conflict avoidance has some enormous downsides. When trying to make peace, for instance, we’re likely to give far too much in an effort to reach compromise quickly. Plus, we don’t like to negotiate. Negotiation is, inherently, conflict. No thanks!

In my life, this is especially problematic in circumstances where I need to stand up for myself. Let me give you an example.

Recently, the roof of our home developed a small leak. After making an initial assessment, I decided it was too much for me to handle one my own. I called a local roofing contractor.

“We can be out tomorrow,” said the man who answered the phone. “But there’s a $250 minimum charge for the trip. That $250 can be applied to the first hour of labor, then each additional hour is $150. Plus, we’ll charge you for materials, of course.”

“Sounds fine,” I said.

The roofing company called me at 8:16 the next morning to let me know they were on their way. They showed up about ten minutes later.

I crawled into the attic with one of the roofers to show them the problem. “That’s not so bad,” he said. “We can fix that quickly.” And they did. At 9:06, the roofers waved good-bye and told me the office would send an invoice. Because they’d been on site less than an hour, I figured the bill would be maybe $400 or $500.

Yes, I noted the time when I was interacting with the roofers. I always try to do this when working with contractors who charge by the hour. And, as you’ll see, it’s smart that I do so.

![Copy of the invoice from the roofing company [Copy of the invoice from the roofing company]](https://www.getrichslowly.org/wp-content/uploads/roofing-invoice.jpg) Last weekend, I received the roofing company’s invoice. They had billed me $850. That might have been okay if there were some justification for the charge, but there wasn’t. The line item was vague.

Last weekend, I received the roofing company’s invoice. They had billed me $850. That might have been okay if there were some justification for the charge, but there wasn’t. The line item was vague.

“What’s wrong?” Kim asked. She could see that I was silently fuming at the piece of paper in my hand.

“The roofing company charged me about twice what I was expecting to fix that leak,” I said.