Today, the Get Rich Slowly summer of books concludes with an excerpt from Cashing Out: Win the Wealth Game by Walking Away from Julien and Kiersten Saunders. Julien and Kiersten are the power couple behind the rich & Regular blog and YouTube channel.

The following excerpt from Cashing Out (published by Portfolio/Penguin) is used with permission. Copyright © 2022 by Rich & Regular LLC. This passage has been edited to be more readable on the web.

Dr. Sue Johnson is a clinical psychologist who specializes in emotionally focused therapy. She says that when couples fight (regardless of the topic), they’re doing a dance. One partner makes a move, and the other one responds accordingly. She insists the dance is always the problem — not you, not me, not us — and not the topic.

Dr. Sue Johnson is a clinical psychologist who specializes in emotionally focused therapy. She says that when couples fight (regardless of the topic), they’re doing a dance. One partner makes a move, and the other one responds accordingly. She insists the dance is always the problem — not you, not me, not us — and not the topic.

By focusing on the dance, we can shift our focus and look at our interaction patterns whenever there’s an issue. The rhythm of one person responding to the other person’s moves is what ultimately. defines the dance, and our ability to instinctively know when to reach and and grab the other’s hand for a spin requires what Dr. Johnson calls emotional attunement.

If the conflict is the dance itself, think of your emotions as the music. Being emotionally attuned means you can both hear the same song, or at the very least can acknowledge that yours isn’t the only song playing. In other words, it’s not enough to just go through the moves together if one of you is grooving to Barry White and the other is swinging to Barry Manilow.

When you’ve been in a pattern of avoiding conversations with your partner about money, it’s as if you’ve both been attending a silent disco. Everyone’s dancing, but you can’t hear any music. If you want to get attuned, it’s important to understand what unresolved money arguments sound like, emotionally speaking.

Name-Calling: Conversations About Spending

Over the years, we’ve met and spoken with hundreds of couples about money, and the most common argument we’ve heard is about spending. Latoya wants to know why her partner has more shoes than an NBA locker room, while Ricky wants to know why his front door has more boxes than an Amazon warehouse.

In most cases, it’s clear that one person dragged the other to us because they needed them to understand something. They’ll say, “Y’all can explain it better than I can,” or, “Every time I try, it just goes in one ear and out the other.” It always reminds us of frustrated pet owners who bring Roscoe to a dog whisperer because nothing they’ve tried has worked: Roscoe just keeps peeing on the couch.

Almost without fail, as they’re detailing the scene of the conflict, someone says something along the lines of “one of us is a saver and the other is a spender”. The premise is rooted in the assumption that the saver is the good guy, the responsible one, the one who makes the best or better decisions about money. On the other hand, the spender is the bad guy, the irresponsible one who always gets it wrong and needs to be fixed.

- For starters, we’re not relationship police doling out punishment to people who overspend at the mall.

- Second, we disagree with any framing that locks people into fixed financial identities. Those labels are just that — labels. And no single label can fully encapsulate anyone’s identity because in reality everyone spends.

The idea of “savers” and “spenders” is simple, convenient, and easy to remember, but it’s not a reflection of the world we live in. Saving and spending are fluid concepts. The only difference between savers and spenders is the time horizon.

Spenders are spending for today. Savers are setting aside money to spend in the future.

For example, if we save $20,000 in one year to buy a car with cash, and then we spend that $20,000 the following year to get it, are we savers or spenders? It depends on which year you ask us, right?

Getting attuned with your partner starts with freeing your relationship from the contraint of labels, and it’s the first step to inviting curiosity back into your conversations. Whenever you’re having a conversation about spending, you need to go into it acknowledging that there are no villains. Your ability to have a non-judgmental conversation about money requires swapping the paradigm from “good or bad” to “now or later”.

J.D.’s note: Please go back and re-read that last sentence. It is so, so important.

Whenever anybody spends money, they’re chasing a feeling, and the goal of the conversation is to find out what that feeling is. Whether it’s wanting to feel security, spontaneity, or pleasure, once you acknowledge that both you and your partner want the same thing — to feel something — the nature of the conversation becomes less about the spender/saver persona you’ve assigned each other and more about looking at the decision objectively and finding new, creative ways to reach the goal.

Couples usually describe their goal as getting on the same page, but it’s important to go much deeper than that. The ultimate goal with your partner should be to achieve a state of harmony, where each person is allowed to express themselves fully in a way that contributes to your collective dance.

Nagging: Conversations About Saving

Not only does nagging strain a relationship, but it’s also guaranteed to put someone on the defensive because of its persistence.

Saving money is an ongoing part of managing your finances. Over time, constant panicky warnings that someone should be saving more erode the ability to look at any situation objectively. This level of surveillance makes sense in totalitarian governments, but in relationships it’s conversational quicksand. The more you do it, the deeper you sink.

Soon, the reminders about money blend with the daily chorus of other unsolicited prompts to wipe the counters or to take out the trash. It all begins to sound like a broken record. If you don’t get the tone right, at some point the person being nagged will start to think that your real beef is with them, and not about the money at all.

Attunement in this area boils down to classic reframing. As we mentioned, saving is just “planning to spend later”, and guess what’s more fun than talking about what we’re not buying in the present? Obsessing over buying it in the future!

Our tried-and-true advice for conversations about saving is to talk about your future plans. Meaningful conversations about future plans act like a release valve, giving a potentially high-pressure situation a chance to stabilize.

Instead of saying, “Babe, what’s with all the Starbucks cups? We need to be saving, not slurping!”, start your request with an “I” statement. That indicates you’re participating in the conversation as a partner, not a parent. For instance: “I’m so excited to upgrade our TV. I think I’m going to cut back on Chipotle to see what kind of dent that makes in our saving goal. Would you consider doing the same for Starbucks? I’ll bet we could have the cash by November and catch a great deal instead of waiting.”

Anticipation is a helluva drug, and there are positive psychological benefits when you look forward to something. Optimism is more reliable than willpower when it comes to doing things you don’t want to do.

For instance, when we had to cut back on eating out in order to save for a vacation, we’d cook foods at home that were reflective of the local cuisine and play their local music to help set the scene. Sometimes we’d even YouTube the destination and watch other people’s experiences and anticipate what we were looking forward to the most. Not only were these small rewards a welcome distraction from another night in, but they also helped us become more disciplined.

Blaming: Conversations About Debt

It’s pretty common for one partner to owe more than the other, and that disparity can lead to feelings of resentment and insecurity. Constant reminders about how much debt somebody brings to a relationship, as well as the approach they use to tackle it, can be a source of tension.

The person with the debt may feel a deep sense of shame from believing their debt means they’re wrong or bad. On the flip side, the person without debt can feel obligated to help pay for it, which can create resentment. Trying to dance to a song that’s composed of shame and obligation is like trying to waltz to “Cotton-Eyed Joe”.

For Kiersten, the shame surrounding her debt triggered defensiveness. She’d mastered her ability to use religious platitudes whenever she didn’t know the answer to something. She was also accustomed to avoiding conflict in other areas of her life and had learned to live among her problems instead of trying to solve them. From that emotional vantage point, our initial conversation about her debt felt like a personal attack. (And to her credit, it was.)

For us, attunement in this particular area required letting go. Kiersten needed to let go of any romantic notions of being rescued, and Julien needed to let go of his judgment. We both needed to let go of popular debt-payoff plans that treated debt as a moral failing, and learned how to strike a balance where frugality and flexibility could coexist.

Once we teamed up, combined our finances, and started to pay off our debt together, we became critical of the social and cultural norms that created it to begin with. We learned to dance together.

Our approach worked well for us, but there are legitimate reasons to tackle your debts separately, like eligibility restrictions on forgiveness plans or just personal preference. In those cases, you can agree that each person is responsible for their debt and that you won’t ever co-sign for loans together unless you both benefit from it equally.

Either was is fine as long as you remember that regardless the path you choose, emotional attunement still makes it a highly coordinated effort where both people contribute to its success or its failure.

“Tell Me More”

In any money conversation you’re having, use the phrase “tell me more” as a way to indicate when you don’t understand your partner or need more context. It’s a signal that more context is needed and follow-up questions will allow a better understanding of the other person’s perspective.

In any money conversation you’re having, use the phrase “tell me more” as a way to indicate when you don’t understand your partner or need more context. It’s a signal that more context is needed and follow-up questions will allow a better understanding of the other person’s perspective.

Judgement and harsh language are the equivalent of placing your finger on record player in the middle of your dance. That sharp and sudden scratch completely wrecks the flow and halts the conversation. But saying “tell me more” is a gentler nudge, inviting the other person to continue expressing themselves and feel encouraged to take a conversational risk.

There’s an important caveat to using “tell me more” in charged situations. It’s impossible to feel curious and inquisitive when you also feel threatened and intimidated.

After our first argument, it took a while for one of us (ahem, Julien) to regain the other’s trust related to sharing financial details. For a long time, one of us (ahem, Kiersten) would cry every time we talked about money because she was overwhelmed and replaying “if I’d known, I never would have dated you” in her head.

In those moments, Julien wasn’t blasting Kiersten with the phrase like a fire extinguisher. In fact, using “tell me more” in times like these can do more harm than good, undermining its future use. In hotbed moments, good old-fashioned patience works best. Instead of forcing flammable conversations, you’re better off preserving the dance floor for future use.

The Get Rich Slowly summer of books continues! Today’s excerpt comes from Jordan Grumet, better known in the FIRE world as Doc G, host of the Earn & Invest Podcast. When he’s not talking about money, Jordan is a real-life hospice doc. His new book, Taking Stock, offers lessons from the dying to the living.

The following is from Taking Stock by Jordan Grumet with permission from Ulysses Press. Copyright © 2022 by Jordan Grumet. This passage has been edited to be more readable on the web.

I used to have a patient who was an undertaker. We had many conversations about philosophy and practicality, and it didn’t take long for me to realize that one must gain profound insights from being engaged in such a unique business. As I was often fond of saying: When the undertaker speaks, you should really listen.

I used to have a patient who was an undertaker. We had many conversations about philosophy and practicality, and it didn’t take long for me to realize that one must gain profound insights from being engaged in such a unique business. As I was often fond of saying: When the undertaker speaks, you should really listen.

Those of us who have made death and dying our business may seem unlikely investment advisers, but because both the undertaker and myself have spent extensive time in close proximity to mortality, we’ve been given unique insight into what’s really worth investing in. What investing tips could someone in my line of business have gleaned from dealing with death and dying? Believe it or not, a few quickly come to mind.

These tips weren’t learned by accompanying the wealthy through this difficult journey — although the wealthy have much to teach. These tips weren’t siphoned off of the personal books of those who had little interest left in hiding their secret ingredients to success. These are simple, straightforward bits of knowledge gained from walking down this lonely path with those reluctant to be making the journey.

And believe it or not, most of what I learned about investing has nothing to do with money.

Invest in Yourself

Personal investment comes in many forms. Chief among these is self-forgiveness.

Remorse is common in humans of all stripes — living and dying — and its effects can be devastating. The specifics may vary: an action taken or not taken, a relationship salvaged or destroyed, or an object bought or sold. The human capacity to blame oneself is unlimited. We spend endless amounts of time feeling bad about things we wish we had done better.

While self-blame serves the purpose of introspection and improving future outcomes, it often leaves a path of destruction it its wake. It’s hard to look forward when you are constantly looking back. The key appears to be changing what we can change and forgiving ourselves for the rest.

While self-blame serves the purpose of introspection and improving future outcomes, it often leaves a path of destruction it its wake. It’s hard to look forward when you are constantly looking back. The key appears to be changing what we can change and forgiving ourselves for the rest.

Losing his job was the least of Gerald’s regrets. Decades before being diagnosed with cirrhosis (chronic liver disease), his exit from corporate America set off a series of events that ended in alcoholism. His marriage fell apart, and he quickly became estranged from his ex-wife and his daughter, Sandy. While sobriety and eventual employment were recoverable, the damage he had done to his body was not. Neither was the estrangement with Sandy.

A large part of the life review process was spent with the social worker exploring his feelings surrounding the loss of his daughter. Gerald eventually was able to find a modicum of peace and forgive himself. He also realized that if this self-forgiveness had been granted earlier, he might have been able to quit alcohol long before his liver became so damaged.

- What have you been unwilling to forgive yourself for?

- What damage is this unwillingness inflicting?

Another common way we invest in ourselves is by slowing down. Often, we have big audacious goals and want to reach them immediately. Yet — as in the story of the turtle and the hare — slow incremental gain is what helps us win the race. If we can make progress toward a major goal by just one percent per month, we’ll have phenomenal annual returns over the long run. This principle applies to a skill, a relationship, or just about anything we strive toward. We mustn’t allow our limiting beliefs to hold us back.

We also need to invest in experiences. Experience compounds over time, just as our monetary assets do. As we learn and grow, we hone skills that make us better employees as well as people. Ask anyone who has risen through the ranks to become CEO of a company. Just like Ben Franklin’s compounding investments, growth in the workplace is anything but linear; it grows exponentially.

And if we are going to talk about investing in ourselves, we would be remiss if we didn’t mention education.

Invest in Education

While there’s no question that I’ve benefited from an expensive four-year college education, there are so many different ways to educate yourself nowadays — read, discuss, take online courses, debate until your face is blue and you walk out of the room disgusted. The world is full of teachers, great and small.

Knowledge is the emergency fund in which you shield your happiness. When all other resources are exhausted, your knowledge will help you secure a job, build a shelter, or make the right decisions at the most critical moments. Don’t skimp on self-improvement, and don’t be afraid to pay for it. The money you spend on education will compound in the form of knowledge and skills.

Say yes — even when you don’t want to. Open yourself to other people’s requests, and jump into an activity that feels foreign or uncomfortable.

The only way to gain knowledge or discover new passions is to be willing to explore. Not only will you be exposed to exciting opportunities, but you’ll also build stronger relationships with those to whom you say yes. Always have your bags packed.

Don’t be afraid to learn new things. I’m continuously surprised by how resistant the average person is to learn about basic finance. Most experts suggest that a few hours of reading each month will make you totally financially competent. Yet the preconceived notion that the subject is too difficult scares many away; don’t let it.

I have watched countless patients die with a book on their nightstand or an unfinished argument circling their brain. This is not sad or trivial. Even those who are dying wake up every morning with a plan for how they will spend each day. Make sure you allow room for acquiring new knowledge. Inquisitive people tend to die as they live: happy and full of questions.

Invest in Other People

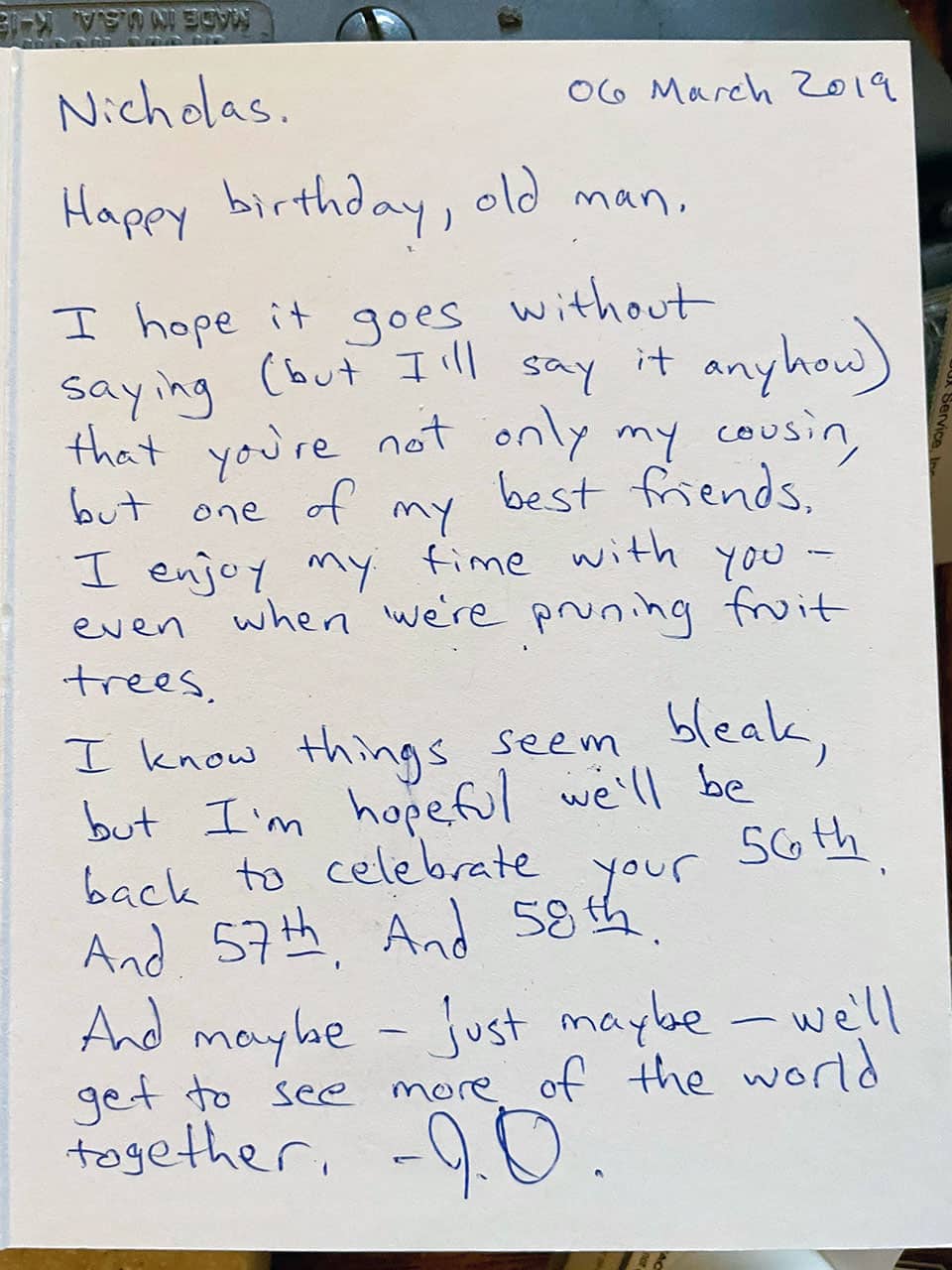

The one measure of a person (rich or poor, happy or sad) is in the people whom the person leaves behind. I can think of no greater indicator of success. I know instantly when I walk into the room of a dying patient whether they have invested in other people. They are surrounded by pictures, letters, cards, and friends.

In fact, I usually know who the successful investors are before I even reach the hospital room. There are people walking in and out; noise and laughter peal through the otherwise somber hallways. Smiles and tears celebrate the bittersweet confluence of life and death.

If you invest in people, the compound interest will multiply into a lifetime of love and happiness. Long after you’re gone, your essence will survive in the smile on the lips of those who shared in your asset allocation.

It took me years to understand this tip. I stumbled about as a doctor looking to find my people in the midst of a community that didn’t fit me. It was only after I discovered writing and podcasting in the personal finance realm that I was able to connect with people who understand me.

These connections have made all the difference; they have given me the courage to redefine my identity and purpose.

Invest in Children

Invest not only your money, but your time and love. Invest in children. Help build the blocks of their adulthood and happiness. Sprinkle them with your knowledge, humility, and kindness. Lead them with your virtuous example. In you, they will find the role model of success and freedom. Teach them about finances so they can understand what money can and can’t do for them in attainment of their life goals. Leave them with a good example of what living looks like.

Investing in your children will produce a lifetime of dividends. They will be the shoulder to lean on and the undertaker of your vast life dreams. Your time on this earth is short, but your progeny will carry on your spark. Like a ripple in a vast ocean, your effect will be carried with them through the generations. You will live on in the hearts and minds of those who come after you.

Every time a colleague accidentally calls me by my father’s name, while rounding at the hospital, is proof of how we live on in our children. His legacy shaped my career and passions even decades after he has passed. He is remembered.

I will never be able to repay my parents for what they have willingly surrendered to me. Instead, I will pay it forward to my own children. I will invest in them in much the same way as my parents have invested in me, and, thus, our goodness will continue on through the generations.

Invest in Physical and Mental Health

Your body and mind are interconnected. They form the framework you build upon. There’s no financial well-being without mental and physical well-being. As this book demonstrates, managing your money and future take forethought and conscientious decision-making. You can’t do this properly if you yourself are unwell.

Invest in mental health by taking the time and energy to recover. Learn how to slow your mind and relax with activities such as meditation, exercise, and listening to classical music. Don’t be afraid to ask for help from family, friends, or mental health professionals. Psychological counseling is not only common but also incredibly helpful. Getting a professional’s outside perspective can make a huge difference in quieting those internal voices that disrupt your peace and calm.

Physical health also plays an important role. Not only may it prolong the time to the end of life, but the emotional benefits are also enduring. We generally feel stronger both physically and emotionally when we are taking positive steps to take care of ourselves. This does not mean that we all have to become marathon runners. As I said before, perfect can be the enemy of good enough.

Try to get at least thirty minutes of physical activity a day. Start with something easy like walking. Find an activity that fulfills your physical needs without being loathsome or burdensome. If you hate doing it, the habit won’t last.

While I don’t feel strongly about alcohol or drugs, anything above recreational use often limits our health as well as our ability to see our goals clearly. If you are wondering whether it’s a problem, then it probably is. Most of the highs these substances give us are artificial and short-lived.

Invest in the Market

Even a collection of investing tips from a hospice doctor would be remiss without the basics. Taking Stock is a personal finance book, after all. So, don’t forget to invest in the stock market:

- Earn more than you spend.

- Save as much as you can each year (20 to 50 percent).

- Buy broad-based low-cost mutual funds.

- Max out retirement savings first, and then open a taxable brokerage account.

- Hire a financial adviser only to advise — not to invest for you.

My hope is that this book gives you the intellectual, tactical, and practical knowledge to get the money right so that you can invest more heavily in the other things I’ve discussed. I don’t want to minimize the importance of understanding the financial basics, but I do want to remind you that they are necessary but not sufficient.

Final Thoughts

These are my investing tips from a hospice doctor. As you can see, only the last section deals with money. The reason, of course, is that finances are the easy part. How you invest the rest of your time and energy is likely to determine your perspective in those waning days when you deal with a doctor like me. Don’t waste your life and regret.

These are my investing tips from a hospice doctor. As you can see, only the last section deals with money. The reason, of course, is that finances are the easy part. How you invest the rest of your time and energy is likely to determine your perspective in those waning days when you deal with a doctor like me. Don’t waste your life and regret.

Start investing now! Before it’s too late. The stronger the foundation you create, the better you’ll be able to deal with the unexpected. Because if you haven’t figured it out yet, that’s the point of investing in the first place.

Your investing plan has to start immediately — before you are dying and the end is so clearly in sight. Building a life of meaning, purpose, and connections takes time and compounding. Investing in yourself takes energy, and investing in education requires work. Building relationships with your children and community will be a mental and physical strain. Taking care of your mind and body will be taxing. Learning about personal finance and building financial security will consume hours that you might rather have spent on something else.

And it’s all so very, very worth it. Be as prepared for life as you would be for death.

Invest in yourself wisely.

Exercise: Non-Monetary Investment Inventory

Clear your schedule for an hour for two to three separate days over the next week. During that time, make sure all electronics are turned to silent, you’re well-rested and fed, and you have found a quiet, comfortable place to concentrate.

Take a sheet of paper, and separate it lengthwise into three separate columns. Number each from 1 to 10.

- For your first list, write down all the education you have received up to this time. You can start with high school, university, or college. Add in any graduate programs, online courses, on-site work trainings, or self-study projects. Be generous here — no need to have received a formal degree or certificate. It’s okay, especially for this section, if you don’t have ten full entries.

- For your second list, write down all your skills. These can range from professional expertise to innate talents to self-taught abilities. Don’t forget all that you’ve learned through social media. Are you a content creator? What about hobbies? Again, give yourself credit. What do people always tell you that you are good at?

- Finally, in the last column write down key relationships. This includes family, friends, work associates, and even acquaintances. List the ten people who have a big influence on your life. This is your community.

Now peruse your three lists together; this is the sum total of your non-monetary investments. What you have created is an inventory of your non-financial wealth. Often, we get so caught up in our net worth calculation that we forget about our non-monetary assets.

If you take your inventory of non-financial wealth and add it to your net worth calculation, you now have a true listing of all your resources. Are these enough to allow you to utilize most of your time pursuing your true purpose, identity, and connections? If so — welcome to financial independence!

Howdy, friends. Sorry for the long lapse between posts. After returning from a brief summer vacation, the GRS database had imploded. Again. We patched things up this morning and can now resume publishing. Over the next couple of weeks, I plan to share excerpts from three recent money books.

The following is from Buy This, Not That by Sam Dogen with permission from Portfolio, an imprint of the Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Kansei Incorporated.

Please note that I’ve edited this passage slightly to (a) be more readable on the web and (b) fit within the publisher’s word-count limitations. Ready? Let’s dive in!

Life is rarely black-and-white, yet we need to make definitive choices all the time.

Life is rarely black-and-white, yet we need to make definitive choices all the time.

- Rent this house or buy that apartment?

- Invest in a growth stock or an index fund?

- Live in San Francisco or Raleigh?

- Join a start-up or work at an established firm?

These choices all involve an expense of time and capital. Each choice brings risk and reward. The problem is that most of the time we don’t have enough information to confidently choose this or that. My approach helps you overcome this information gap.

You do this by thinking in probabilities instead of in binary terms, where it’s an all-or-nothing proposition. If you start thinking in probabilities instead of absolutes, you’ll develop a stronger analytical mindset to make more winning decisions over time. You’ll also be able to make more winning decisions on risks that others never dare take.

Positive-Expected-Value Decisions

One of the biggest decision-making fallacies people fall victim to is thinking they must take action only when there’s 100% certainty of success. Here are two examples.

- Only if you are certain someone likes you — because they told their friend, who told you — do you feel confident asking them out. But you might find out years in the future that they liked you as well and were just waiting on you to make the first move.

- Most people put in an offer on a house only once it’s listed for sale. But at any given moment, there may be several homeowners in your neighborhood looking to sell, unsure whether they want to go through the hassle of listing their property. By sending out friendly letters of interest, you could very well start a dialogue and end up buying one of the most coveted houses on the block for a good price.

Your goal is to constantly make positive-expected-value decisions in everything you do. A positive-expected-value decision is when you have a greater than 50% probability of your desired outcome coming true.

Some decisions have higher expected values than others, such as accepting a job offer with a guaranteed raise and promotion with a growing company known to cut costs. Some decisions, on the other hand, have murkier expected values due to an overwhelming amount of incomplete information.

It’s up to you to do your due diligence to bring your probability of success as close to 100% as possible (while also accepting that very few decisions ever have 100% positive outcomes). There are few sure things in life. So think in probabilities.

The more important the decision you need to make, the higher the edge or positive expected value you should have.

The 70/30 Framework

Now that you understand the importance of making positive-expected-value decisions, let me introduce you to my 70/30 philosophy in decision-making.

The 70/30 framework states that you should seek to make a decision only if you have at least a 70% probability of making an optimal decision. At the same time, have the humility to understand that 30% of the time, you’ll make a suboptimal decision and have to live with the consequences.

With more than a two-to-one reward-to-risk ratio, over the long run you’ll become very profitable with this decision-making strategy. You’ll most certainly have regrets where you’ll wish for do-overs. However, you’ll also constantly be learning from your mistakes so that you can make even higher positive-expected-value decisions in the future.

But don’t get cocky. That’s when you’ll run the risk of financial and personal ruin. Being overconfident and not properly recognizing risks will be your downfall. The worst mistake you can make is not realizing when a good decision was mostly due to luck, not skill. Proper risk management is paramount.

Expert marketing has also made so many things seem like attractive products, experiences, or investments. But of course, not everything you spend money on or invest in turns out to be as great as expected. Therefore, it’s up to you to continually hone the accuracy of your predictions so that they aren’t too far from reality. If your predictions are way off, it’s imperative that you study why — and make adjustments.

How to Improve Your Forecasting Abilities

The best way to improve your forecasting abilities is to constantly make predictions about uncertain outcomes. For example, if you watch any type of sporting event, before the game starts, make a forecast of who will win, by how how much, and why. Jot your forecasts down to keep yourself honest. Then compare the outcome with your expectations and see what you go wrong and why.

You can practice improving your predictions on practically any type of activity that has an uncertain result. You can make forecasts on:

- which dog will win the dog show

- how long a friend’s relationship will last

- how much a house will ultimately sell for and by when

- how long your injury will take to heal

- how many times you’ll test for COVID until your results are negative again

Soon you’ll start to naturally see everything as a probability matrix. Where others make decisions based solely on gut instinct, you’ll go into every decision-making process based on extensive practice, logic, and self-awareness. This is your competitive advantage.

When you’re dead wrong, you must review the reasons why and learn from them. Eventually you’ll narrow the gap between various outcomes and your expectations to the point where you can confidently say something has at least a 70% probability of succeeding. If you feel your desired outcome has more than double the chance of coming true over the undesired outcome, you’re on the right track.

Buy This, Not That is not only a book about achieving financial freedom sooner, it’s also a book about making optimal choices for some of life’s most important decisions. For each decision, I’ll present to you the rationale for why I think you should go a certain way based on what’s best for your particular circumstances. My reasoning is based on my own experience, my background in finance, and the perspectives of more than 90 million people who’ve visited Financial Samurai since 2009.

Not everything will turn out according to plan. We must embrace this truth. However, so long as you continually learn from your mistakes, your decision-making skills will surely improve over time.

Get on the Damn Bus

Buy This, Not That isn’t only about optimizing your choices; it’s also about optimizing your attitude.

Buy This, Not That isn’t only about optimizing your choices; it’s also about optimizing your attitude.

I came to America with my family from Kuala Lumpur. I was born in Manila while my parents, who worked for the U.S. Foreign Service, were stationed there. We lived in Zambia, the Philippines, Virginia, Japan, Taiwan, and Malaysia, in that order, before coming to northern Virginia when I was fourteen years old. At the time, only about 6% of the population in our town looked like me. It was quite a shock going from being a part of the majority to being a minority.

I had to start over and find new friends while also navigating encounters with bullying and racism. I was also a misfit who lacked the ability to think quickly because my mind constantly bounced between English and Mandarin. My grades and SAT scores were unremarkable too.

I knew my parents weren’t rich. They drove beaters and frowned on ordering any drink other than water when we went out to eat. We lived in a modest townhouse in a grungier part of town. I never had a Nintendo. My Air Jordans were hand-me-downs from a friend and two sizes too large. We weren’t poor, but we never had more than what we truly needed.

After high school, I attended William & Mary, a public university in Willamsburg, Virginia. We couldn’t afford a higher-priced school, and I wasn’t smart enough or athletic enough to get scholarships. I did well enough at William & Mary, but that’s not how I ended up getting a job at Goldman Sachs after college. The only reason I got a job at Goldman Sachs was because I got on a 6:00 a.m. bus one chilly Saturday morning.

The bus was heading from college to a career fair two hours away in Washington, D.C. Twenty other students signed up to attend, but I was the only person who showed up. After waiting over an hour for the no-shows, the bus driver took me to his company’s headquarters, swapped out the bus for a black Lincoln Town car, and personally chauffeured me to the fair. This was the first time I realize that just showing up is more than half the battle.

Seven months, six rounds, and fifty-five interviews later, I finally got the job at One New York Plaza, Goldman’s equities headquarters. All because I showed up and stuck with it.

Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine I could leave the corporate grind at age thirty-four to focus on my life’s passions. But thanks to Financial Samurai and my investing efforts, I’m now forty-five and financially free to spend time with my wife and two kids, and to work on the things I love.

One saying keeps me going whenever things are hard and I feel like making excuses: “Never fail due to a lack of effort, because effort requires no skill.” I can fail because the competition was too good, or because an unforeseen event knocked me off my feet. But if I fail because I just didn’t try hard enough, I know I’ll be filled with regret as an old man.

Grit, consistency, and confidence are by far the most important attributes for achieving your goals. Don’t think you need to have special skills, innate talent, or rich parents to get ahead. Who you are is good enough already.

Hello, friends! I have a lot to say, and I’ve done a lot of work on Get Rich Slowly during the past three weeks, but most of my efforts aren’t yet ready for public consumption.

- The site de-design is 95% complete, but that final five percent is fiddly. I could be ready to launch the new layout tomorrow — or it might be two weeks. It’s tough to say. If you’re curious, though, you can check out my current progress here. But be warned that the site isn’t fully functional. (For fun, I mocked up this very post in the new format so you can see the difference.)

- I have several long articles in the works — quality! the internet is dying! the sunk-cost fallacy! — but nothing that’s wholly finished. And with my attention more focused on the de-design and Real Life than on writing, it’ll probably be a while before anything is complete enough to publish.

Still, I thought it’d be fun to stop in with a J. Money-esque stream-of-consciousness post to share a some cool projects from some of my friends.

Speaking of J. Money, let’s start there.

Bringing Sexy Back

I know that there’s a huge crossover between folks who’ve been reading Get Rich Slowly for a long time and folks who loved Budgets Are Sexy before J. Money left the site. Well, guess what? J. Money is bringing sexy back. That’s right: J. Money has re-purchased the site, and he’s begun publishing new stuff regularly. Yay!

In other blogging news, I’d like to share my current favorite read: Money and Meaning from my buddy Douglas Tsoi. Douglas and I met a few years ago and have formed a solid connection. He’s a deep thinker, and I like that.

Douglas and I presented a financial workshop together at World Domination Summit in 2019. I bought his 1993 Toyota pickup from him at the end of that year. (Boy, does Kim hate having that thing parked in front of our house!) And in February of this year, he launched Money and Meaning through Substack. It’s truly terrific. You should check it out.

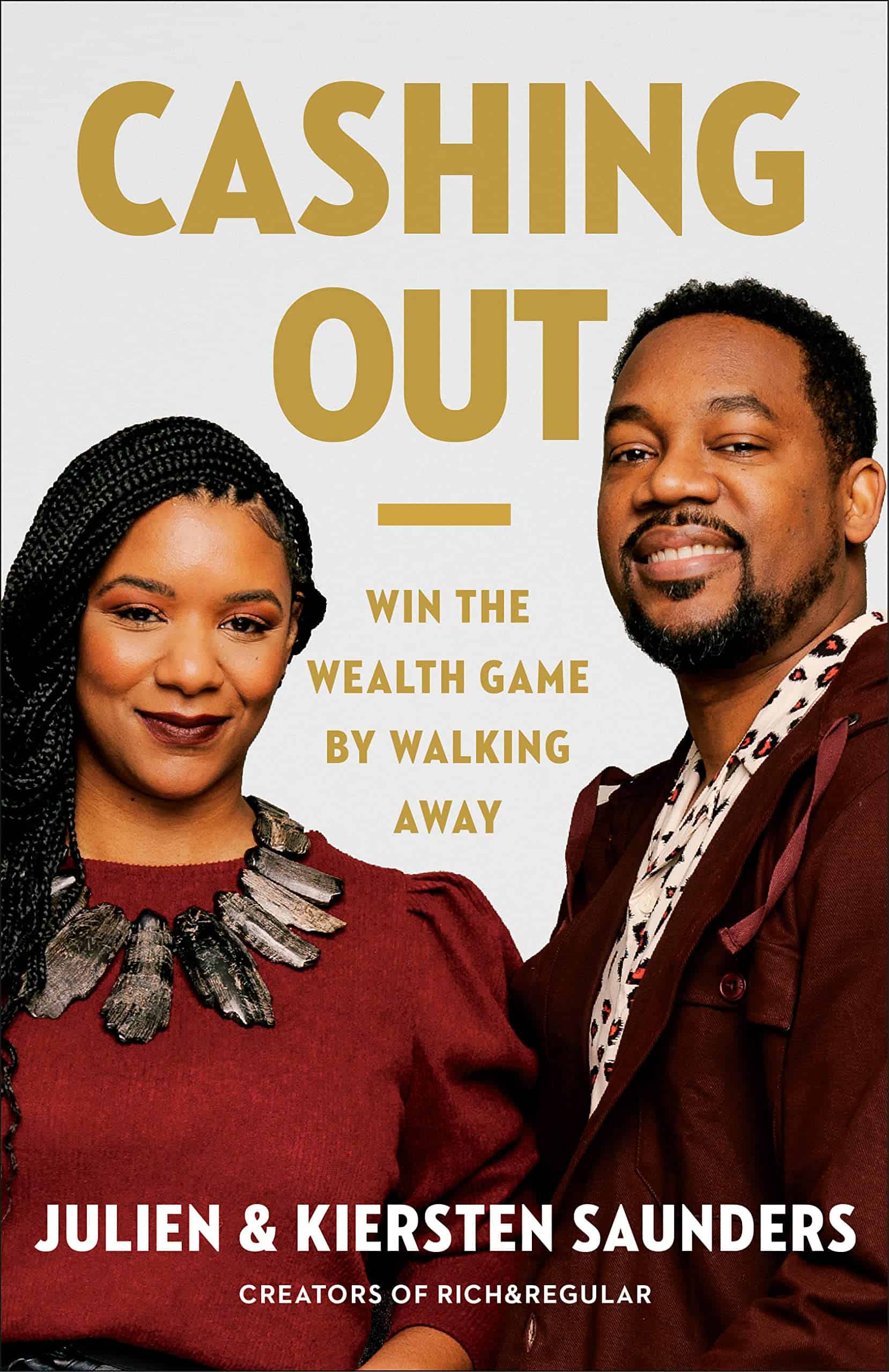

Cashing Out

You know what else is terrific? Kiersten and Julien Saunders from the rich®ULAR blog have published their new book, Cashing Out. I no longer review friends’ books at GRS (because that’s truly a Kobayashi Maru), but I will say this: I read an advance copy of Cashing Out and thought it was great.

Here’s what I wrote to Kiersten in Julien in February after reading their book:

K&J,

I deeply appreciate that your book isn’t just a re-hash of the same stuff everybody has already said. You go deeper. You talk about society, culture, relationships, and psychology. I believe this stuff is far more important than merely mastering the mechanics of money. The mechanics are simple. (They may not be easy, but they’re simple.) These other things are what make money management complicated, and they’re too often ignored. You’ve written an excellent book, and I’m happy to help promote it.

Anyhow, here’s what I came up with for a blurb. I hope that it’s useful.

“Cashing Out is important and inspirational. Kiersten and Julien avoid the B.S. that plagues most money manuals, opting instead to provide readers with the knowledge and confidence necessary to save, invest, and — in time — cash out by cashing in on the American Dream. Highly recommended.” — J.D. Roth, founder Get Rich Slowly

Thanks and good luck, my friends!

–j.d.

Taking Stock

Speaking of books, I’m excited that my friend Doc G is close to releasing his book, Taking Stock. It’ll be out on August 2nd.

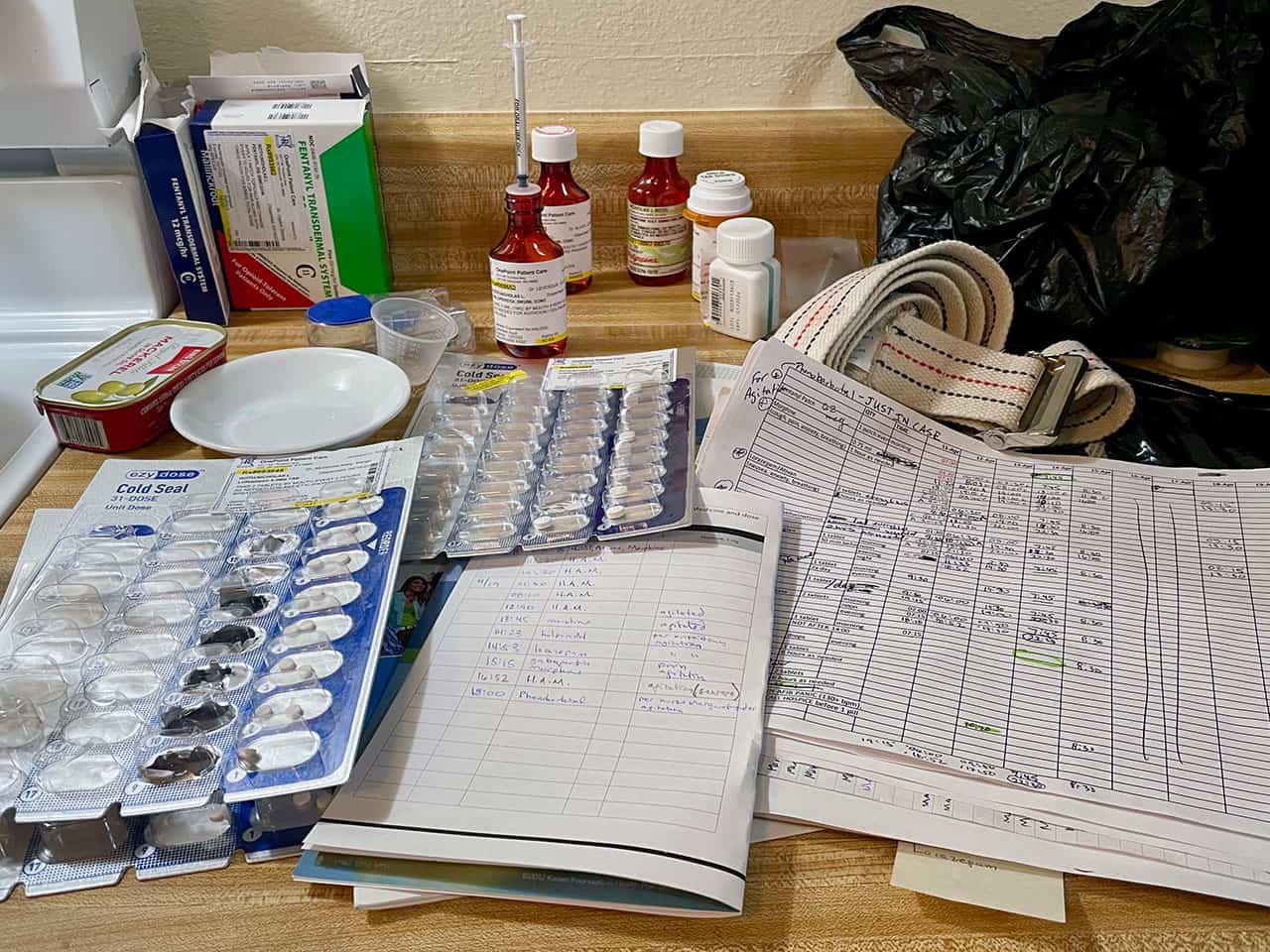

For those unfamiliar, Doc G (a.k.a. Jordan Grumet) is a hospice doc who also hosts the excellent Earn & Invest podcast. He and I roomed together at a past Camp FI, and we’ve had several terrific discussions over the years. (Near the end of my cousin Duane’s life, Doc G helped talk me through what was coming next.)

Here are two videos promoting Taking Stock: the book trailer, and a conversation between Doc G and Grant Sabatier. (Note that despite my best intentions and ample opportunity, I still have not read this book. Sometimes I am a bad friend. 🙁 )

Oh, and speaking of Grant Sabatier (notice how one subject is naturally leading to another here? crazy!), earlier this year he partnered with The Motley Fool to produce a course called Financial Freedom in Uncertain Times. I’m honored to have been one of the folks interviewed for the project, along with Doc G, Kiersten & Julien, Jamila Souffrant, Stefanie O’Connell Rodriguez, Bola Sokundi, and Amanda Holden.

Again, I haven’t had time to work through the course, but I’ve talked with Grant extensively about it, and I know that our interview was deep and insightful. I suspect the course contains quality material, and I do hope to dive into it in the future.

Buy This, Not That

While we’re discussing the future, I should mention the upcoming book from Sam Dogen, a.k.a. The Financial Samurai. Sam is a polarizing figure in the world of personal finance, and I get that. But even when I disagree with him, I find his writing thought-provoking and often truly insightful.

Sam’s new book is called Buy This, Not That and it comes out on July 19th. I haven’t read it yet — the postman legit placed a preview copy in my hands three hours ago — but I plan to do so after I finish Doc G’s book.

During a recent email exchange, Sam had this to say about Buy This, Not That:

The book is more than just trying to achieve financial independence. It’s also about how to make more optimal decisions to live your best life possible. […]

I read a dozen books as research before writing my book. I wanted to see what worked and what did not. And the key missing elements from many of the good books were specific action items and frameworks to follow based on different situations. I also wanted to write about a decision making framework on how to tackle some of life‘s biggest dilemmas. Real life stuff that go beyond money.

As a side note, my brother used Eat This, Not That to help him figure out food and lose weight. For a long time now (since the beginning of GRS, I think), I’ve wanted to do a similar “Buy This, Not That” series on the blog, but never figured out a way to make it work. I’m glad Sam has.

Little Miss Evil

To close things out today, I want to mention something fun. I’m sure many of you are familiar with Bryce and Kristy from Millennial Revolution, which is one of the few money blogs I still read regularly. Well, these two don’t just write about money. Several years ago, they also published a kids’ book called Little Miss Evil.

I’m reading Little Miss Evil right now and it’s a heck of a lot of fun. I love the core idea: What’s it like to grow up with a super-villain for a father? A super-villain who uses a nuclear bomb for a coffee table?

I always enjoy seeing my personal finance friends do other stuff — making art, producing music, climbing mountains, brewing beer — and that’s certainly true in this case.

Okay, that’s it for today. I didn’t intend to spend two hours writing about all of these things, but hey — it’s stuff I’ve been meaning to share. Maybe you’ll enjoy one or more of these projects from my friends.

Oh, one last thing: Old comments are really, truly gone. That’s right: More than fifteen years of comments here at Get Rich Slowly have vanished into the ether.

Well, that’s not wholly correct. The comments still exist in the database, but for some reason they have all become disconnected from the articles they belong to. We have no idea how it happened, and there doesn’t seem to be a way to fix it. I’m bummed, as you can imagine. It’s a huge, huge loss. But neither Tom nor I can come up with a solution to restoring them.

Interest rates on home mortgages are rising rapidly across the United States, which seems to be slowing most housing markets. (Some, like the market here in Corvallis, have been less affected. Give it time.)

The average mortgage rate for a 30-year loan was about 3.0% at the start of the year; today, it’s at 6.245% — even for somebody with an excellent credit score over 800.

Kim and I are fortunate that we bought our home in 2021 instead of waiting until 2022. Mortgage rates weren’t actually a factor during our deliberations last year; the historically low rates were simply an added bonus for buying when we did.

When we purchased our home last August, we took out a $480,000 mortgage at 2.625%. We didn’t hit the precise bottom of the mortgage market (that was early January 2021, when we might have had a loan for 2.5%), but we came close.

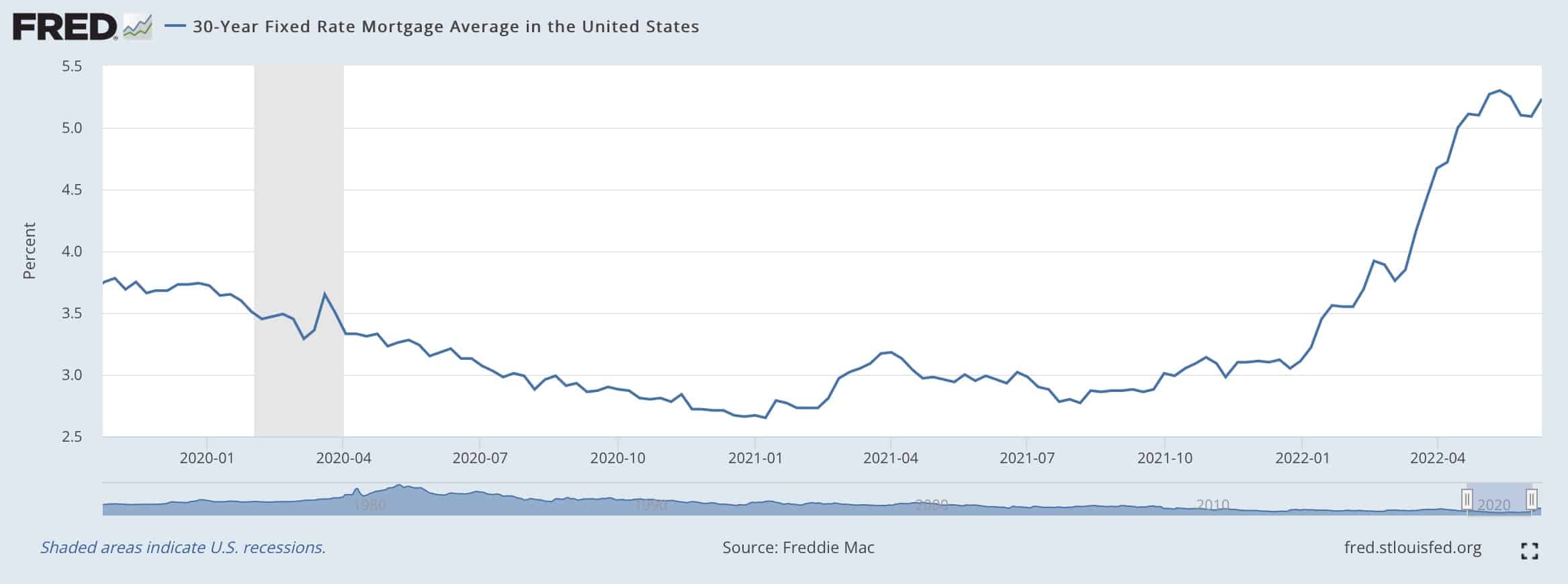

Here’s a chart from the Federal Reserve that shows mortgage rates from the past 2.5 years.

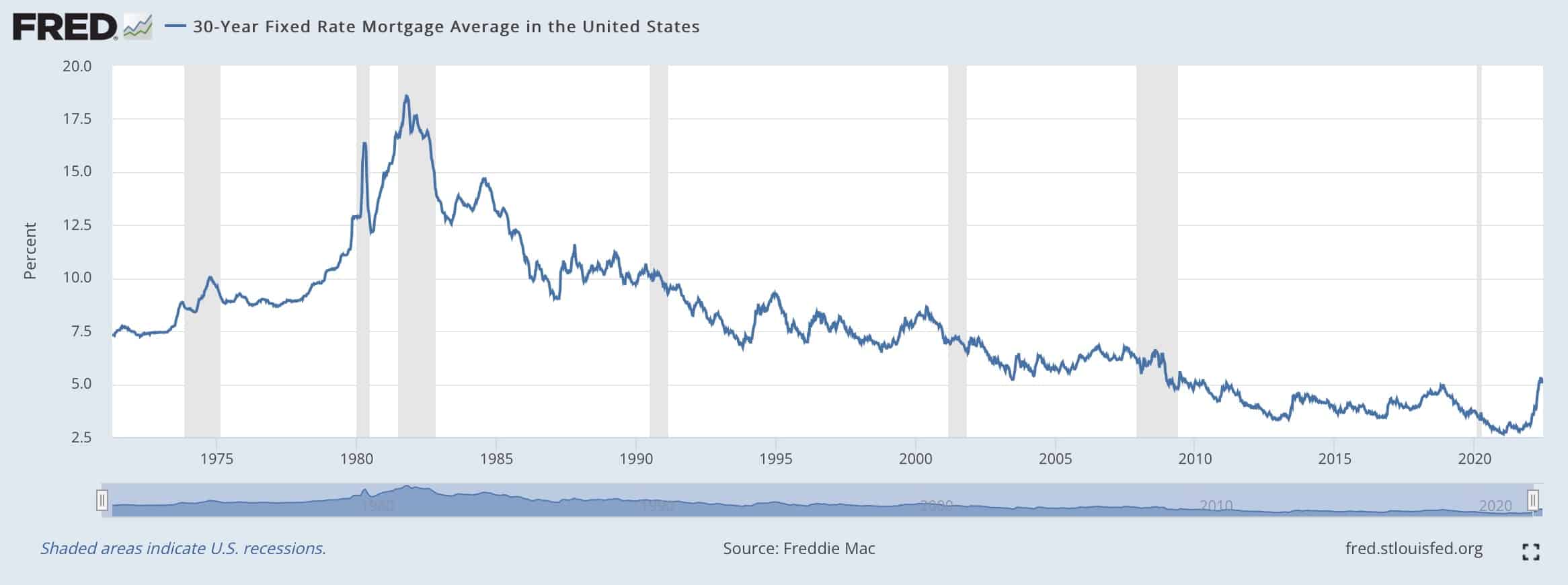

And here’s a chart that shows mortgage rates for the past 50+ years:

Mortgage rates have hovered at historic lows since the Great Recession of 2007-2009. And rates fell even further during the COVID pandemic. (These low rates are partly responsible for the blazing-hot housing market of the past two years.)

What do these rising mortgage rates mean to actual home buyers? Let’s use our situation as a representative example.

Rising Rates Decrease Buying Power

Last August, Kim and I closed on our home here in Corvallis. It’s a 1964 behemoth for which we paid $680,000. With a $200,000 down payment, we managed to get a 2.625% APR on a 30-year loan. We pay $1929.33 each month for principal and interest. (Our actual mortgage payment, including taxes and insurance, is $2528.43 per month.)

Today, that same loan would cost us 6.245%. If we wanted to buy this same house at the same price with the same down payment, our monthly payments for principal and interest would be $2956.04 — an increase of over $1000 per month compared to buying a year ago!

If we were shopping for homes today and wanted to keep our mortgage payment the same — $1929.33 per month — we’d have to lower our sights. Instead of taking out a $480,000 mortgage on a $680,000 home, we’d be looking at a $313,500 mortgage on a $513,500 home.

But wait! That’s not all! Home prices in our town have risen 10% during the past year, so that would further compromise our buying power. If we had waited until now to buy and wanted to keep our mortgage payment at $1929.33, we’d be shopping for homes that cost $467,000. Delaying a year would have decreased our buying power by $213,000 — over 30%.

While low mortgage rates didn’t spur us to move last year, they certainly gave us an incentive to act quickly. Conversely, if we had waited until this year, I’m not sure what we would have done. Knowing me and my aversion to onerous debt, I probably would have been reluctant to take out a mortgage. I would have tried to find a home to buy with cash, limiting my options even further.

When mortgage rates are at crazy lows like 2.625%, I don’t think twice about carrying a mortgage. It’s a no-brainer. I want a mortgage on my home every single time, and I never want to pay it off. A rate of 2.625% isn’t free money (and I don’t want to pretend that it is), but it’s pretty damn cheap. The gap between expected long-term stock returns (6.8%) and our mortgage rate (2.625%) is huge. There’s a lot of room there, a big margin for error.

On the other hand, there’s almost no gap between a rate of 6.245% and expected market returns of 6.8%. There’s no margin for error. I’m wary of borrowing money at this rate, especially such a large amount. I’d rather not have a mortgage with rates this high.

What Does the Future Hold?

I expect that rising interest rates will have their intended effect: They’ll cool the blazing-hot housing market. Will prices drop? Probably. But who knows? It’s clear, though, that a shift is coming.

I have a handful of friends who are real-estate agents. If you too have real-estate agent friends, then you know that they tend to be permabulls when it comes to their industry. They have an unflagging belief in the future of home prices. But even my real-estate friends believe some sort of shift has begun.

Here’s a long (and interesting) Facebook comment from one of my real-estate friends:

Last year, home prices were high, but those high prices were mitigated by super-low interest rates on home loans. Now you’ve got a double whammy: high prices and high rates. Today seems like an especially poor time to purchase a home. That’s not a good combo.

I feel sorry for folks who absolutely must move right now. They’re getting screwed.

A couple of weekends ago, Kim and I enjoyed a short vacation on the Oregon Coast. She’s been taking foraging classes, and she had an early morning workshop on harvesting sea vegetables one Sunday. Rather than wake in the middle of the night to drive out, we rented a small place in Tillamook and took the dog for an adventure. (The dog loves the coast.)

We let Tally lead us on a walk through town one rainy afternoon. Coming home, we cut through a trailer park. “We’re in the poor part of town,” Kim said.

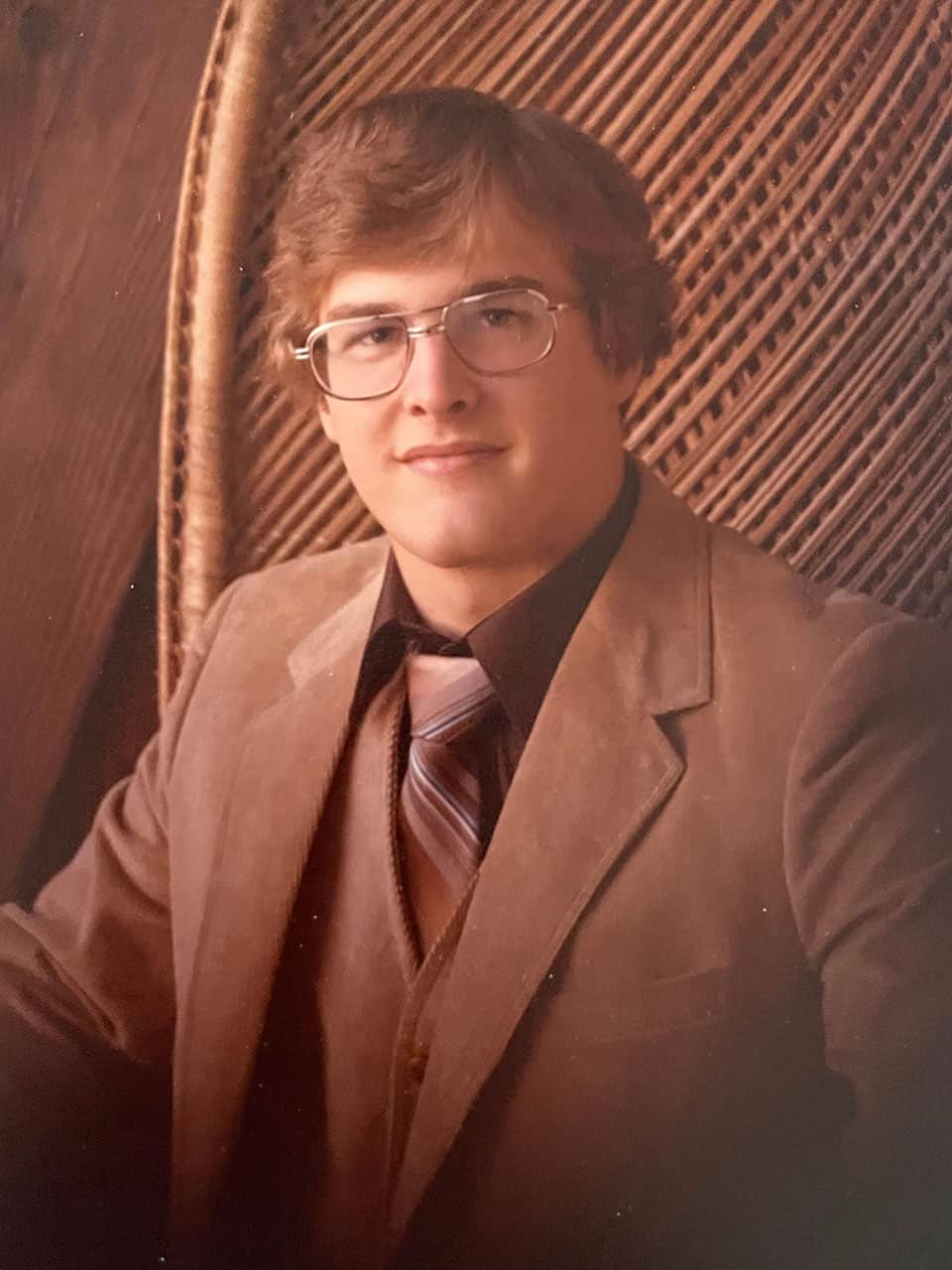

“Yep,” I said. “But look at that trailer house right there. That is almost exactly like the one I grew up in.” Here’s the trailer I grew up in:

We stopped to look at the trailer. I pointed out the tiny windows and the sagging roof. “It’s small,” Kim said, frowning.

“Yes,” I said. “Yes it is.” The trailer was a beat-up 1970-era single-wide. Nothing about it looked appealing. I could imagine the inside: shag carpet, thin wood paneling on the walls, faded linoleum, colors like Avocado and Harvest Gold on every surface.

If you’ve been watching Stranger Things season four, as we have, the trailer houses in that show remind me of ours too. Look at this mobile home from Stranger Things; it’s very, very similar to the one my parents owned:

Everything about that image feels like my childhood to me. (Well, except for the demonic tentacles wrapped around the house and car…)

Growing Up Poor

I’ve talked before about how my family was poor when I was young. When he was working, Dad didn’t make much money — but he was often out of work. Mom bought our clothes from the discount rack. There were times we relied on the church “relief society” for food. Mom and Dad often tried to make our situation seem like an adventure (“Kerosene lamps are fun!” “A wood stove provides more heat than a furnace!” “We don’t need a TV! TV rots your brain!”) but in retrospect, I know now they were doing whatever they could to make ends meet.

There was indeed a brief time when Mom and Dad had money coming in. Dad started a business in 1976 that slowly grew into a profitable venture. When he sold that business in 1980, though, the buyer went bankrupt after making only one payment. Poof! There went Easy Street. And, of course, when Mom and Did did have money, they spent it. They never ever saved or invested.

It wasn’t just my mother and father either. My Dad’s entire family was poor. (My mother’s family was not, but we had little contact with them.)

My cousin Duane’s family, who lived about ten miles from us, was poor too. They had a big old drafty house instead of a trailer, but they also struggled to get by. His mother and father, like mine, were all about self-sufficiency. They grew their own food. They hunted. They fished. They built what they could by hand.

Duane loved to tell the story of how his father once refused to buy washers at the hardware store because they were too expensive. They cost seven or eight cents, or maybe a dime. Instead, Uncle Norman went home and drilled holes through nickels to make his own washers.

My father’s sister and her family were just as poor as the rest of us. They lived up in the foothills outside Estacada in another big old drafty house. They needed a big house because there were nine children in the family. When I see movies featuring poor country folk from the 1930s, their circumstances often remind me of Aunt Virginia’s bunch. (Long-time readers will recall that I’ve shared some stories from my aunt’s family here at GRS in the past: “A Six-Dollar Christmas” and “The Night That Mama Cried While Angels Sang”.)

Naturally, the poverty of these three siblings had a source: their parents. Grandma and Grandpa were poor too, although it didn’t seem that way when I was a boy. To me, Grandma and Grandpa were rich. Sure, their house was small. Sure, they lived simply. Sure, they grew much of their own food (in the form of gardens and livestock). Sure, they chopped their own firewood. Sure, they rarely bought anything beyond necessities. But their home and yard were always clean and tidy. And they could both make small things — oatmeal cookies, Bobbsey Twins books — seem like lavish luxuries.

Friends with Money

During my early childhood, our life seemed to revolve around the extended family. We spent holidays with Grandma and Grandpa and aunts and uncles and cousins. Outside of church, this was the only life I knew. To me, this was how the entire world lived. I had no conception that there might be anything else.

During those rare times I was allowed to watch TV, I saw different ways of living, of course, but these seemed like fantasy. Besides, the Cunninghams on Happy Days and the Bunkers on All in the Family didn’t have lives that seemed too far removed from ours — except that they lived in the city. (The Brady Bunch, on the other hand, blew my mind. Such a big house! Such nice things! They were rich, and I knew it.)

Eventually, I made friends and I started to visit my friends’ homes. Those friends who lived in the country sometimes lived in the same circumstances that we did, but many did not. Many had bigger homes, nicer homes, cleaner homes. (You would not believe me if I described how dirty and cluttered our house was when I was young.) And my friends who lived in town? Well, there was no question in my mind that they were rich.

I remember going to an overnight birthday party in town when I was in fourth or fifth grade. My friend’s house was huge. It was modern. He had so many books and toys. His parents had new, fancy cars. They ate in restaurants. They could afford to take the entire birthday party to pizza! Looking back, it’s probable that this friend’s family was only middle class, but in 1980 they seemed rich to me.

As I entered middle school and high school, the differences between our circumstances and those of my classmates became even more apparent to me. Again, not all of my peers were rich. Some were poor like us, and they tended to become my friends. But I have vivid memories of my first experiences in the homes of rich people, and of how these rich kids carried themselves.

Once during high school, for instance, I went over to a friend’s house after play practice. (We were rehearsing You Can’t Take It With You.)

My friend’s father was a dentist — my dentist. Their house, located on the shore of the Willamette River, was enormous. It was so big that there was an actual tree growing in the center of it. It was a smallish tree, but it was still a tree. My friend and her brother each had their own computer. They each had their own television. The family had so much. I was in awe.

During high school, I had brief encounters like this with wealth and wealthy people. In each case, I felt out of place. I felt dirty. I felt like an impostor.

It was also about this time that I began to notice a difference between the rich kids and the poor kids like me. The rich kids exuded confidence. When they wanted something, they asked for it — or they took it. We poor kids were much more timid. We never took anything, and often we were afraid to ask for what we wanted. We were rule followers. My rich friends were not. They behaved as if rules were meant for other people. (Inevitably, it was my rich friends who got into trouble. Just as inevitably, their parents bailed them out.)

A Higher Education

I awakened to the difference between rich and poor during my teenage years. And I awakened to the knowledge that my family was poor. I began to think about my future. I never explicitly thought, “I want to be rich” or, “I don’t want to be poor.” Instead, I thought, “I don’t want to live in a trailer house when I grow up.” It seemed to me that the best possible escape route was college.

Fortunately, I was smart. I didn’t particularly apply myself to my studies, but I didn’t need to. I coasted through high school with a 3.29 GPA with zero effort. I never had homework (I finished it in class or during lunch) and I never studied for exams. I did phenomenally well on standardized tests. I could write well. I participated in a wide range of activities. In time, I was accepted to every college I applied to (although, admittedly, I didn’t cast a wide net). And one school, Willamette University, offered me a full-ride scholarship based on my test scores and extra-curricular activities.

College was a shock. I was discomforted by my rich friends in high school, but that was nothing compared to the wealthy kids I met in the dorms. These kids had nice clothes, nice cars, and (seemingly) no cares. Again, they had so much confidence. They acted as if the world was made for them. How did they do it?

One of my friends, for instance, had a new BMW that his parents had bought him for high school graduation. His father was a doctor. My friend (and his sister, who also attended Willamette) weren’t especially smart. In fact, they were kind of dumb. I tutored both of them at different times, and was always amazed by how little basic knowledge they possessed, and by how poor their study skills were. They didn’t get into college on merit. They got into college because their father with deep pockets was an alumnus.

My friend and his sister sailed through college with poor grades and a rich social life. They were active in their Greek organizations. Their parents gave them money, which they promptly wasted on drugs and alcohol. To them, college wasn’t about studying. College was about making connections.

I know it sounds as if I have negative feelings toward these two friends, but I don’t. I loved them both. I have only fond memories of them. But there’s no question that they were rich kids who acted like rich kids.

Once during my freshman year, I visited my friend’s house. It was like a palace to me, and I said so. My friend was offended. To him, his house was a house. He took it for granted. But the place was enormous. It was opulent. I remember standing in front of the floor-to-ceiling wall of windows that looked out over the valley below us and watching the sun rise. I’d never experienced anything like that before.

At the end of my freshman year, I began dating a woman from Portland. Amy was terrific, and so was the rest of her family. But again, their life was outside my realm of experience. They owned a big old home in a nice part of town. Her father was a real-estate agent who owned several rental properties, including the building where he had his office. Amy’s mother (who couldn’t remember my name, so she called me “The Initials”) was a wonderful woman who was interested in the arts and philanthropic organizations. “Your family is rich,” I told my girlfriend once. She was offended, but it was true.

I had many experiences like this during college. In time, I became numb to them. I would visit a friend’s childhood home, and it would look nothing like what I had grown up with. Always always always, I felt out of place. I didn’t know how to behave. I didn’t know what to do or think or say when in the presence of such wealth. But all of my friends seemed to fit in fine. They’d grown up in this world, and they knew its unwritten rules.

This is no small thing.

The Mental Side of Money

I’ve been fortunate in life. When we were married, Kris and I started with modest means. We lived in an apartment. Before long, we bought a standard ranch house near the high school where she taught physics and chemistry. We weren’t rich but we were certainly middle class. In fact, by the time my father died in 1995, Kris and I had a home and lifestyle that surpassed what Mom and Dad had ever been able to achieve.

Dad’s box factory did eventually allow him to escape poverty, but he didn’t live long enough to truly enjoy it. And Mom’s health declined before she could enjoy the change in financial fortunes either. Today, the box factory pays for her memory care and medical bills.

As an adult, my experience has been markedly different than when I was a kid. I’ve gradually moved from poverty to middle class to upper middle class. In the physical world, I am now rich. But inside? In my internal world? I’m still that poor kid living in a trailer house. Foolish though it may seem, I am trapped by those thoughts and those emotions. They guide my decisions (often at an unseen level).

I still lack confidence. I still feel like I don’t deserve anything that I have. I still expect it all to vanish, to go away. I find it difficult to defer gratification. Intellectually, I understand that if I want to purchase something, I can do so any time I need to. I can wait. Emotionally, however, I feel like I have to buy things now because the opportunity may never arise again. It’s irrational, I know, but that’s how it is.

Last week, I had a conversation with a new friend here in Corvallis. I was talking about how frequently Kim and I have moved during our ten years together, and about how we’re ready to stay in one place. “In retrospect,” I said, “we probably should never have sold our condo in Portland. It was a beautiful place. It was the best unit in the building: top floor, on the corner, with a view that looked over the river toward downtown. It was, by far, the nicest place that I have ever lived.”

“So why did you move?” my new friend asked.

“There were a couple of reasons,” I said. “We acquired pets, for one. We had two cats and a puppy, and they didn’t do well on the top floor of an apartment building. Plus, the crime and traffic and homelessness in our neighborhood had become overwhelming. But if I’m being honest, I think the main reason I sold the place was because I felt like I didn’t deserve it.”

“What?” my friend said, shocked. “Didn’t deserve it?”

“I’m serious,” I said. “I’ve never really thought about this before, but it’s true. During the four years we lived there, it never felt real. It felt like a dream. It felt like the place was too good for me. I felt like I didn’t deserve it. I felt like an impostor.”

She and I then had a long discussion about coming from a poor background (because my new friend grew up poor too) and how poverty can mess with your mind, can lead you to conflate wealth with self-worth.

On a whim, I just looked up our old condo unit on Zillow. It just sold again two months ago! I bought it for $342,000 in 2013. It sold for $737,000 two months ago today. I think you can get a sense of just how posh the apartment was.

The Green-Eyed Monster

All of this rambling was inspired by a post I saw yesterday on the /r/fatFIRE forum on Reddit.

For those unfamiliar, /r/fatFIRE is a judgment-free place for rich people to talk about rich people problems. These are folks worth $5 million or $10 million or $100 million. Generally speaking, I do not begrudge these people their wealth. (I’ve never been one to envy the wealthy, actually. I’m not an anti-billionaire, “eat the rich” kind of guy.) That said, this question triggered some deep-seated issues inside me:

Our child is going a private four year east coast college. We are FAT but trying not to spoil him. All of our trusts are confidential and completely discretionary. He went to a private high school but does have a summer job. I want him to enjoy school and studying. What is a reasonable allowance per month for him? 529 will cover most of her other costs (housing, travel, books, etc). I don’t want him to be the spoiled trust fund kid that I hated in college.

Besides being unclear on this child’s gender (him? her? why does the poster use both?), I was floored by this question. I’m not so much floored by the idea that a kid’s parents might pay for their entire education — I’ve seen that plenty — as I am by the entirety of what’s going on here: private high school, trust funds, a college allowance.

An allowance in college? Are you kidding me?

I’m serious: Even after a day to think about this, I still can’t get over the concept. Do you know how much money my parents directly contributed to my college experience? Zero dollars. And I knew that’s how it was going to be, which is why I pursued scholarships and grants and why I worked several jobs concurrently to have spending money. But it’s not just that this Reddit question is far removed from my own life; it’s also that I think it’s a terrible, terrible idea. (My own experience has shown me just how spoiled kids like this can get. The Millionaire Next Door, though, backs this up with data.)

But what if I’m simply being jealous? What if I’m not flabbergasted; what if I’m actually envious? Does this situation get me riled up because I wish that I’d had the same advantages? And what if I had enjoyed the same advantages? What would I be like then? Would I have turned out spoiled too? Is the confidence I see in wealthy people produced by being spoiled? I don’t know.

My mental health, which was woeful for several years there, has improved considerably during the past twelve months. (There are a variety of reasons for this.) All the same, I still suffer from some of the same core problems that have plagued me my entire life: lack of confidence, poor self-esteem, rotten impulse control. I look at my peers and they all seem to have their shit together. They’re poised. They have direction. They act with purpose. Not me!

I can’t say that growing up poor is the sole source of my hang-ups. Part of the problem is simply my genetic makeup, I’m sure. Part of the problem comes from the fact that my parents, who did the very best they could, weren’t able to impart certain fundamental skills. Part of the problem stems from being picked on all the time during grade school.

But you know what? The older I get, the more I believe that many of my faulty mental models exist because I grew up poor.

What do you think? What’s your experience? Did you grow up poor? Middle class? Rich? How do you think your family’s financial circumstances during childhood affected who you are today? Are you richer or poorer than your parents? To you, do there seem to be differences between the choices and actions of the wealthy and the poor?

Last month, the Federal Reserve released a new report: Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021 [PDF]. This annual survey gauges American financial health and attitudes. The 2021 edition was conducted last November.

Here are some highlights from the report:

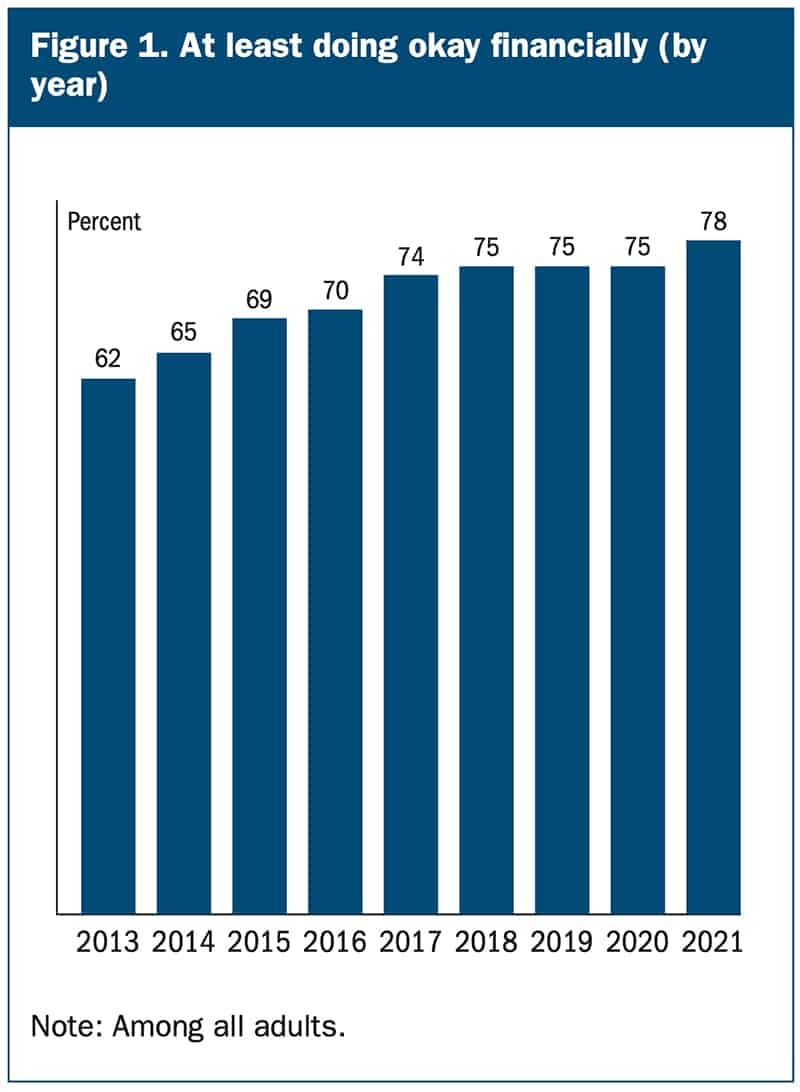

- Seventy-eight percent of adults were either doing okay or living comfortably financially, the highest share with this level of financial well-being since the survey began in 2013.

- Fifteen percent of adults with income less than $50,000 struggled to pay their bills because of varying monthly income.

- Fifteen percent of workers said they were in a different job than twelve months earlier. Just over six in ten people who changed jobs said their new job was better overall, compared with one in ten who said that it was worse.

- Sixty-eight percent of adults said they would cover a $400 emergency expense exclusively using cash or its equivalent, up from 50 percent who would pay this way when the survey began in 2013. (Note that this survey is the original source of this oft-quoted statistic.)

- Six percent of adults did not have a bank account. Eleven percent of adults with a bank account paid an overdraft fee in the previous twelve months.

These little nuggets of info are interesting, sure, but what I find even more interesting are the charts and graphs documenting long-term trends.

The Demographics of Economic Well-Being

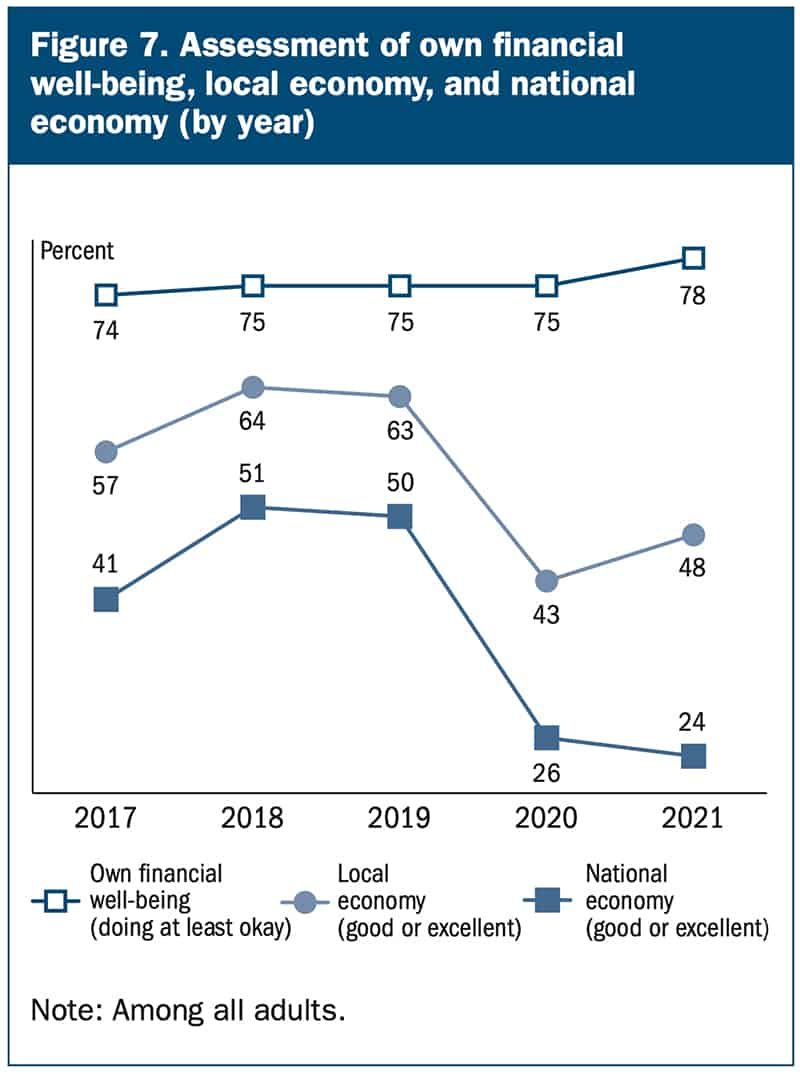

Here, for instance, is a chart that shows how people feel about their current financial situation:

In 2021, 78% of adults in this country reported “doing okay” or “living comfortably”. That’s up significantly from when this survey started in 2013.

The next logical question, of course, is how different demographics feel about their financial situation. The Fed report offers some insight into that.

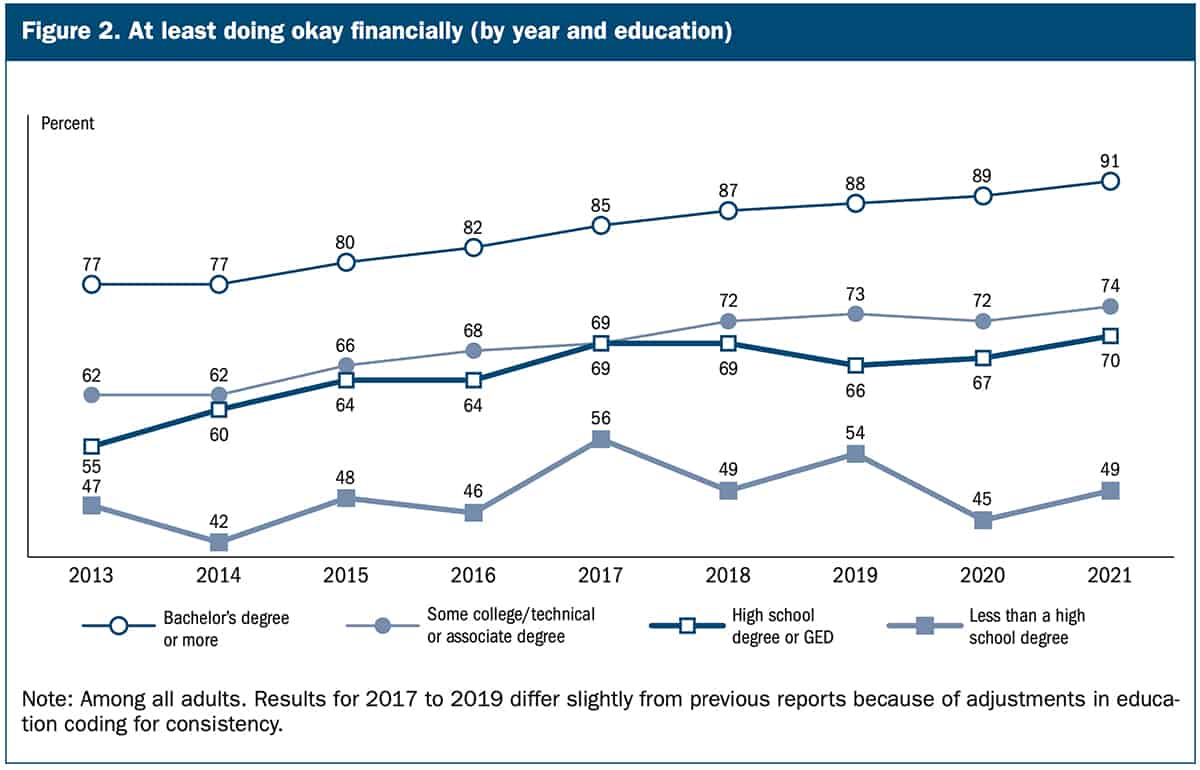

Here’s a chart that shows (once again) the value of a college degree).

Although it’s popular in some corners to bad-mouth college degrees, according to the U.S. Census Bureau (and many other sources) your education has a greater impact on lifetime earning potential than any other demographic factor. Education matters more than age. Education matters more than race. Education matters more than gender. When it comes to making money, education matters most.

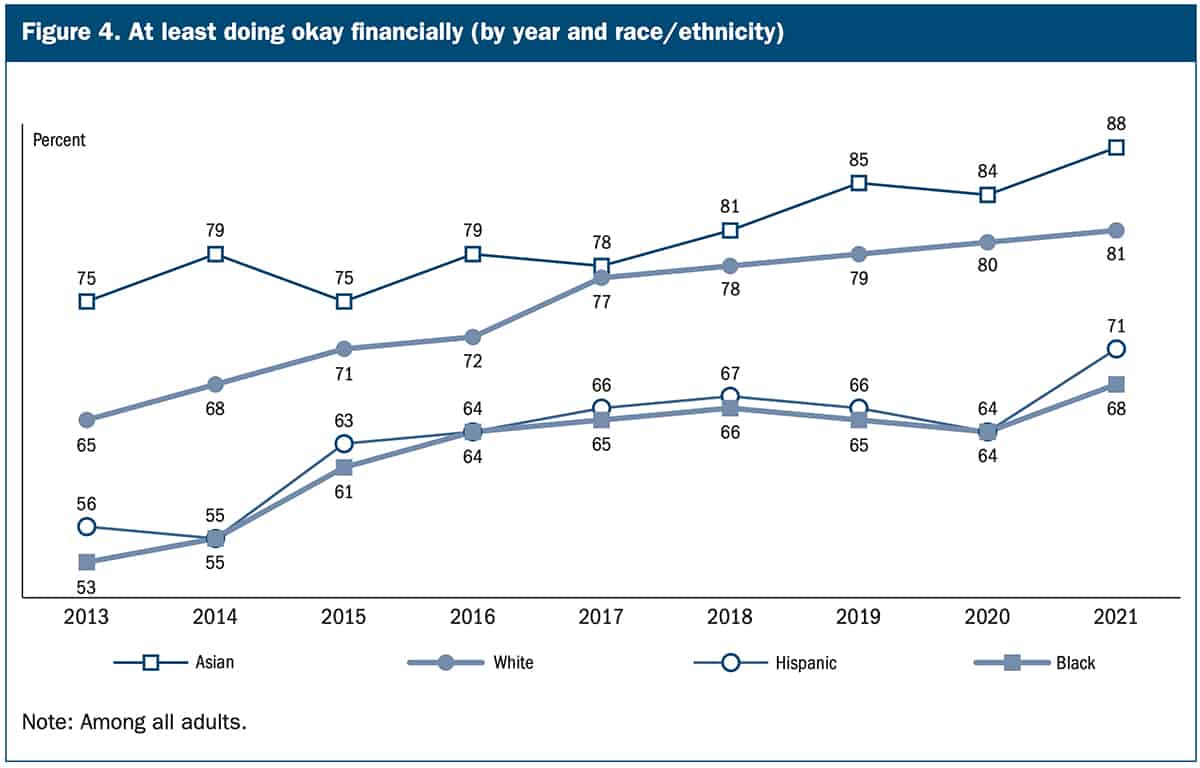

Next, here’s a chart from the Fed report that documents economic well-being by race and ethnicity:

It seems that economic well-being has improved across the board during the past decade.

Personal Well-Being Versus National Well-Being

To me, however, the most interesting chart is this one, which compares respondents’ assessments of their personal well-being with their assessment of local and national economies. Look at this chart and tell me what you make of it. (I have an opinion, but I want you to develop your own hypothesis before reading mine…)

From the report:

Similar to people’s perceptions of their local economy, the share rating the national economy favorably fell precipitously from 2019 to 2020, after the onset of the pandemic ). However, people’s perceptions of the national economy continued to decline in 2021. Only 24 percent of adults rated the national economy as ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ in 2021, down 2 percentage points from 2020 and about half the rate seen in 2019. This trend contrasts starkly with people’s increasingly favorable assessment of their own financial well-being.

The Fed report tells us this discrepancy exists but it doesn’t tell us why it exists. Why do 78% of Americans say that their own financial situation is at least okay, but nearly the same number believe that the national economy isn’t doing well? I don’t know. But I can think of two possible reasons.

First, perhaps most Americans have learned to manage money. Perhaps they’ve been reading money blogs and listening to money podcasts, and now the lessons have sunk in. Maybe they’ve begun saving and investing wisely over the past fifteen years so that their personal economy is now protected from the gyrations of the economy at large.

Perhaps.

I harbor a suspicion, however, that there’s something else at play here.

Long-time readers know how much I abhor the news media. The mass media does not report reality. If you envision life as a bell curve (or “normal distribution”, if you prefer), the mass media tends to report solely outlier events — especially negative outlier events. The vast majority of our lives comprise normal, positive, healthy interactions and relationships and conditions. The news doesn’t report these.

In this case, I can’t help but wonder whether this disparity between perceptions of personal economic well-being and national economic well-being are driven (at least in part) by negative economic news, news that highlights the problems with our economy rather than the things that are going right.

That’s what I think. What do you think? What’s the reason for this gap in perception?

Final Thoughts

There’s much more data and insight in this 92-page report. I’ve highlighted only some stats from the first section on overall financial well-being. Other sections cover income, employment, unexpected expenses, banking and credit, housing, education, student loans, retirement and investments, and more.

I found the section on student loans interesting too. It contains a number of insights. Borrowers with less education, for example, are more likely to be behind on loan payments. This makes some sense, I think. Meanwhile, fewer people are behind on payments than two years ago (and this applies across all demographics).

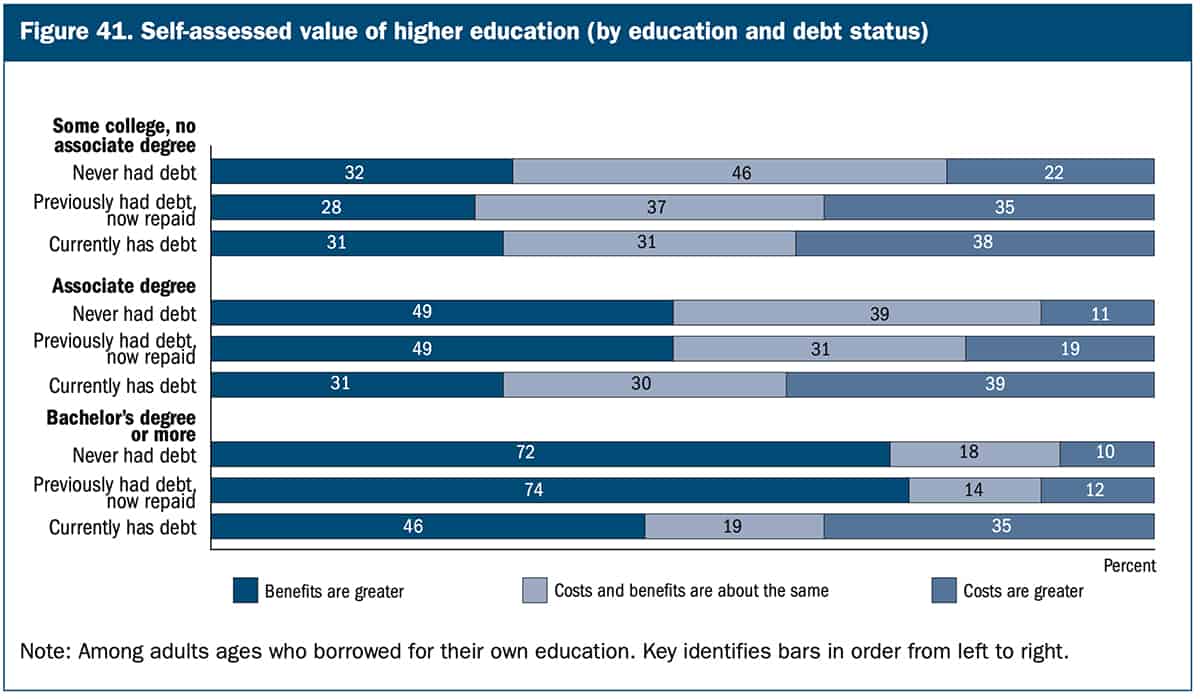

Here, though, is my favorite chart from the entire report. It measures the self-assessed value of higher education:

Two things seem clear here. First, folks who never had to borrow for college believe their education is worth more. Second, the more education one obtains, the more valuable it seems.

Okay, a third thing. Compare this chart with the one I shared earlier that highlights financial well-being by level of education. It’s clear that (objectively) education does improve financial health. But those who have student loans can’t always see that. Their subjective experience seems to contradict the data. Interesting…

Anyhow, the Fed’s Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021 is filled with interesting info. It’s worth reading (or skimming) the next time you sit down to waste time on the internet!

Both my ex-wife (Kris) and my current girlfriend (Kim) tell me I get too worked up about things sometimes. “You over-react,” they both tell me. Maybe so. I prefer to think of myself as passionate.

One of the things I’m passionate about is scammers. I hate them. Scammers are evil, evil people who prey on the most vulnerable members of society. They take advantage of social constructs in order to manipulate people into parting with their hard-earned money.

No surprise then that one of my favorite sub-genres of YouTube videos is “scammers getting scammed”. Scambaiters are modern-day heroes. As much as I despise scammers, I think scambatiers deserve high praise.

Today, I’ve collected together several YouTube videos (representing a couple of hours of viewing) that document, in an entertaining fashion, how scambaiters uncover scams, help victims, and are now actively working with law-enforcement agencies in an attempt to thwart the bad guys.

Scamming the Scammers

First up, here’s a year-old YouTube video from Mark Rober in which he shows how he managed to use one of his famous glitterbombs to catch a phone scammer, who was then arrested.

Rober didn’t do this on his own. He collaborated with some well-known YouTubers who specifically work to thwart scammers. Here, for instance, is Jim Browning’s video about the above incident: Catching Money Mules.

And here’s the Scammer Payback channel working with Rober. I like this video quite a bit, actually. It provides a lot of info.

But wait! That’s not all! Here’s another Rober video from a couple of weeks ago in which he documents his year-long quest to infiltrate the scam call centers in India in order to disrupt their operations (and, he hopes, to shut some of them down).

And let’s wrap things up with Kitboga as he trolls a scammer into spending ten hours with him, eventually goading the crook into losing his temper in a nuclear-level meltdown. It’s a thing of beauty. (Note, however, that the video is nearly ninety minutes long.)

I have zero patience for scammers. Zero. I believe they deserve the harshest possible punishments. But, as Rober mentions in one video, it’s like playing whack-a-mole. You put one scammer out of business and five more rise to take his place.

Aside

In one of his sequels to Dune, Frank Herbert wrote: “Between depriving a man of one hour from his life and depriving him of his life there exists only a difference of degree. You have done violence to him, consumed his energy.”Let’s extend this comparison. If time is money (or, more precisely, money is a manifestation of the time required to create it), if money represents “life energy”, as the authors of Your Money or Your Life put it, then depriving a person of her money is also only different from murder by a matter of degrees.

Further Reading

Want more info on scams and how to prevent them? Here are some intersting articles and useful resources I’ve found over the years:

- How to avoid a scam. [U.S. Federal Trade Commmission]

- Scammers have bilked consumers out of $545 million in COVID-related fraud. [CNBC]

- Who scams the scammers? Meet the scambaiters. [The Guardian]

- Ten ways to spot financial scams (and how to defend yourself). [Bitches Get Riches]

- “I accidentally uncovered a nationwide scam on Airbnb.” [Vice]

Let me know if there are other videos or resources I should add to this list!

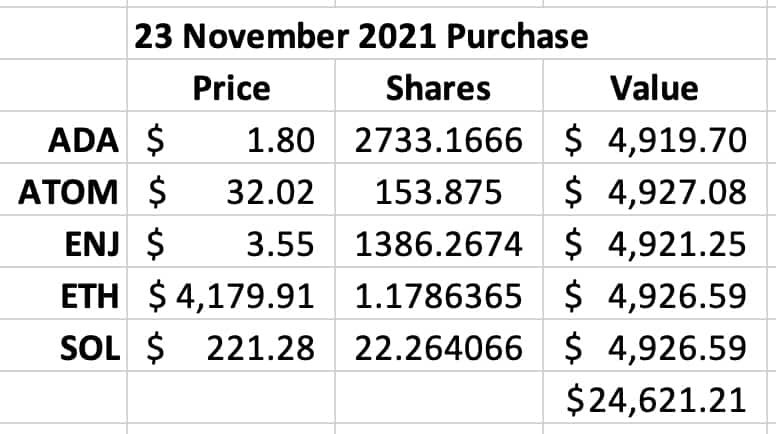

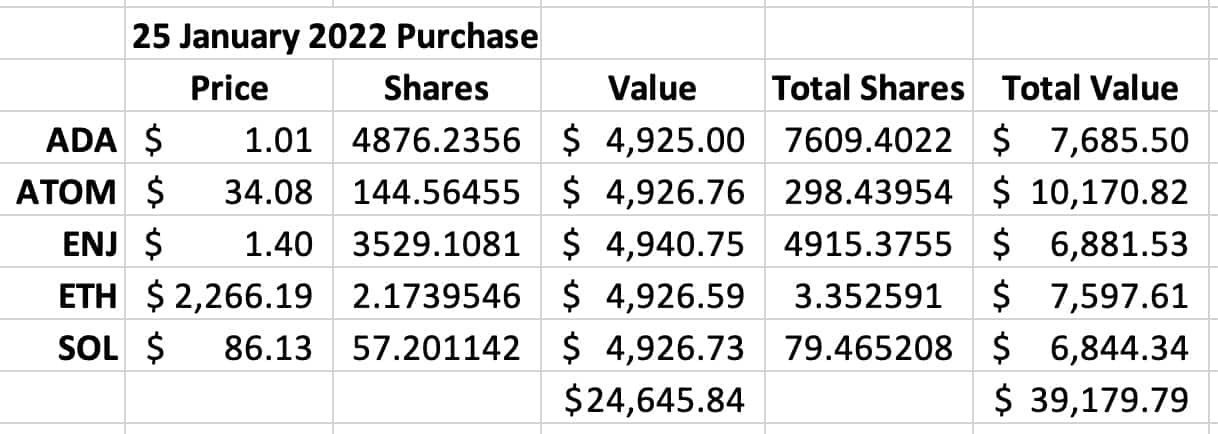

One morning just over ten years ago, I had an interesting conversation at the Crossfit gym. I was “rolling out” — using a foam roller to break up tissue — with the usual group of guys, when one of my buddies brought up this new thing called Bitcoin.

“Bitcoin is digital money,” he said. “But it’s completely private and not tied to a government.”